FOR a while, it was looking like the Wild Wild East here. After essentially sealing the country off from foreign architects for much of the 20th century, the Chinese government kicked off the 21st by turning itself into the biggest single patron of avant-garde architecture in the world.

FOR a while, it was looking like the Wild Wild East here. After essentially sealing the country off from foreign architects for much of the 20th century, the Chinese government kicked off the 21st by turning itself into the biggest single patron of avant-garde architecture in the world.

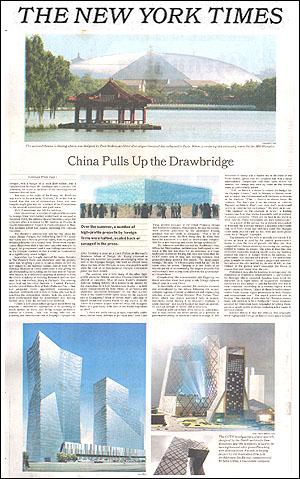

Many of the projects were commissioned for the 2008 Olympic Games, for which Beijing originally planned to spend a staggering $37 billion more than three times what Athens paid as it remade the city and its infrastructure. The proposed new venues include a 100,000-seat Olympic stadium by the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron wrapped in a "bird's nest" of tangled columns, and a swimming center by the Australian firm PTW with a facade of translucent, lightweight panels to be inflated to resemble huge bubbles.

The rest of Beijing was hardly left out. The French architect Paul Andreu designed a $300 million, dome-shaped national theater for the heart of the city. Norman Foster and his London-based firm Foster & Partners offered a new $2 billion airport based on a dragon motif. And after an extensive international competition two years ago, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas was chosen to build what his firm has called its "most ambitious project ever": a dramatic new headquarters for CCTV, China's state-run broadcast company. The looping, O-shaped skyscraper, with a budget of at least $600 million, was a collaboration between Mr. Koolhaas and a partner, Ole Scheeren, for a site in the heart of the booming central business district here.

But even in the midst of the frenzy, Mr. Koolhaas was wary. In his new book, "Content," he writes that he feared that the era of adventurous form and vast budgets might give way to "a refusal of the Promethean in the name of correctness and good sense."

Well, Prometheus has left the building.

Over the summer, a number of high-profile projects by foreign firms were halted, scaled back or savaged in the press. First, the national theater became a target for criticism after a terminal by Mr. Andreu at Charles de Gaulle International Airport in Paris collapsed in May. The accident killed four people, including two Chinese travelers.

The theater's construction was too far along for major design changes, but before long the CCTV tower had fallen into a kind of political limbo, with its groundbreaking delayed for a second time. There were reports (since disproven) that it had been canceled outright. In August the government said it was halting construction on the Olympic stadium so that it could be reconceived at a significantly lower budget.

September has brought more of the same. Reports in The People's Daily and elsewhere said the government was weighing a plan to scrap as many as half the new venues for the Summer Games. And on Sept. 10, the National Museum of China announced it was giving the job of expanding its building, on the east side of Tiananmen Square, to a collaborating group of architects from the China Academy of Building Research and the German firm von Gerkan, Marg & Partners. The winning team beat out two other finalists Foster& Partners and the United States firm of Kohn Pedersen Fox that had proposed more aggressively contemporary schemes. Architects and critics in China, who had been watching the competition closely, took the results as fresh confirmation that the government was moving further away from the architectural forefront.

"There is now a real debate going on about these big projects whether it's appropriate to be spending so much money on them, and hiring foreign architects instead of Chinese," said Yan Huang, who led the planning and construction side of Beijing's Olympic bid. After finishing a year as a Loeb Fellow at Harvard's Graduate School of Design, Ms. Huang returned to Beijing this summer and joined an emerging effort to rein in the Olympic budget. She said no official news about the fate of the Olympic venues was possible until after the visit of an International Olympic Committee panel late next month. The question now is how many of the other high-profile plans for Beijing and other Chinese cities will be altered or canceled. What of Zaha Hadid's dramatic mid-rise Beijing towers, or a similar-scale project by the Australian firm Lab Architecture Studio in both cases commissioned by Soho China, an architecturally ambitious real-estate company? Or, for that matter, what of Ms. Hadid's sleek opera house for the southern city of Guangzhou? What of Steven Holl's collection of linked residential towers slated for the capital, or the Foster & Partners airport scheme? What will Shanghai build as it gets ready to be host of the World Exposition in 2010?

The question now is how many of the other high-profile plans for Beijing and other Chinese cities will be altered or canceled. What of Zaha Hadid's dramatic mid-rise Beijing towers, or a similar-scale project by the Australian firm Lab Architecture Studio in both cases commissioned by Soho China, an architecturally ambitious real-estate company? Or, for that matter, what of Ms. Hadid's sleek opera house for the southern city of Guangzhou? What of Steven Holl's collection of linked residential towers slated for the capital, or the Foster & Partners airport scheme? What will Shanghai build as it gets ready to be host of the World Exposition in 2010?

"I think the really daring designs, especially public ones, will be more difficult to get built now," said Leon Yang, general manager of the Urban Planning Design and Research Company. Nonetheless, he said the nationwide interest generated by the prominent Beijing projects was not likely to disappear. "For a lot of medium-size cities, the first thing they do when they have the resources is to hold an international competition for a new building and invite foreign architects."

Mr. Scheeren said that his and Mr. Koolhaas's firm, Office for Metropolitan Architecture, had signed a contract in the last few days for an extension to a huge bookstore in central Beijing and received news that the CCTV tower was at long last moving forward, with groundbreaking possible this month. "So, surprisingly enough," he said, "it's been a good week for us." At the same time, he added, "Beijing is in the midst of an intense period of re-examining the largest projects that will certainly have a long-term effect on the architectural climate here."

Complicating the reassessment are lingering national anxieties about how great a role foreign cultures should play in a new China.

In the middle of the summer, for example, alarmed and emboldened by the debate following the airport collapse, a group of senior architecture and engineering scholars wrote to Prime Minister Wen Jiabao. Their letter, which was widely published here in August, reportedly called Herzog & de Meuron's stadium "a white elephant" and said it focused too much on aesthetics and not enough on safety and practicality.

Chinese political debate often relies on indirection, and in that context the letter served as a preview of government policy as much as a prod to change it. The reference to safety was a loaded one in the wake of the Paris deaths; given that the proposal had won a large international competition and then been vetted for months, the charge was seen by some on the Herzog team as particularly unfair.

"O.K., so there is a desire to reduce the budget for the Olympic Games," said Ai Weiwei, a Chinese artist and architect who collaborated with the Swiss architects on the stadium. "Fine there's no shame there. Be realistic. But don't use it as an excuse to criticize Western architects. Don't say they don't understand safety or construction technology." He went on to say: "The engineer on the stadium is Arup," a leading engineering firm that works frequently with prominent European architects. "They are the best in the world at what they do. These complaints are pure nationalism."

As a result of the uproar, the architects were asked to redesign the stadium without a planned retractable roof, with fewer seats and with less steel. The changes come amid pointed calls by Mr. Wen and other politicians for a "frugal" Olympics.

Explanations of the shift in attitude are varied. It is driven at least in part by the central government's desire to slow the rate of growth. (In May, Mr. Wen compared the Chinese economy to a racing car, saying it needed to reduce its speed.) The price of steel has also increased markedly, making nearly every big building project the source of budget worries. In addition, the government has announced a desire the anti-Athens plan, it might be called to have large-scale construction all over the city finished by the end of 2007, so that visitors to the games won't encounter the forest of cranes that now tower over the city.

Politicians may also be reacting to outrage over the demolition of traditional neighborhoods particularly the hutongs where extended families have lived for centuries in a tight fabric of single-story buildings connected by thin alleys and the forcible eviction of their residents. According to a Human Rights Watch report issued in March, "Many of these forced evictions violate basic human rights protections in both Chinese and international law." The report predicted that in Beijing, "the clearing of new sites for Olympics venues likely will continue to be a flashpoint." Some residents selected for relocation have responded by killing themselves in grisly public protests, including a few cases of self-immolation.

Another theory is that the officials who originally chose high-profile foreign architects were more focused on their celebrity than on the experimental nature of their work. "I had people come to me," said Yung Ho Chang, a Chinese architect who studied and taught in the United States and returned to Beijing to start a firm called Atelier FCJZ, "and ask: `Who are the very best architects in the United States and Europe? Who are the most famous?' When they hired these name architects, I don't think they really understood what they were getting. I don't think they understand that Rem, for example, was going to push the envelope as much as he did."

Examples of an emphasis on architectural celebrity either seeking it out or creating it abound in Beijing. A real estate firm called the Modern Investment Group, for example, is now selling units in planned residential towers in Beijing by the Austrian firm Baumschlager & Eberle, led by Dietmar Eberle. Along one side of a hallway on the ground floor of its Beijing offices, the group has installed an architectural museum of sorts, a tribute to the great modern form-givers. In the center of the pantheon, squeezed directly between Frank Lloyd Wright and I. M. Pei, is a panel dedicated to Mr. Eberle, who despite a successful practice is not exactly a household name. "He is included to show our clients that he belongs in the company of these great architects," explained Chen Yin, the Modern Investment Group's vice president.

For their part, most foreign architects working in China say the challenge of doing business here these days is not ignorance about contemporary Western architecture. It is, rather, a decision-making process that can be maddeningly opaque and vulnerable to unpredictable shifts in the political currents. "The Chinese aren't shocked by avant-garde designs," said Jacques Herzog of Herzog & de Meuron. "Actually, they are very pragmatic and thoughtful about them. But a huge amount of patience and strategic cleverness is required to get them built. You have to rely on advisers who really understand Chinese culture. And even if you do all of that, maybe you still fail."

Finally, the discussion here about the prominence of foreign architects has played on worries about the extent to which, as the nation continues to modernize, it will need to rely on outside expertise. That anxiety has been intensified by the fact that most of the public buildings by foreign architects are planned for Beijing in the case of Paul Andreu's National Theater, close enough to the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square that the famous portrait of Mao seems to be watching dubiously over its construction.

"Beijing has not traditionally been the laboratory for new kinds of culture," said Luo Li, secretary general of Beijing's Architecture Biennial, whose inaugural edition begins tomorrow and runs through Oct. 6. "It's been Shanghai, or cities even farther away from the central government."

It was perhaps unfortunate that Mr. Andreu's National Theater was the first of the big new projects in Beijing to break ground. Given the combination of its symbolically charged site and the fatal airport collapse, it has been easy for critics to suggest that the entire crop of new architecture will be a heavy-handed, even destructive presence.

But the more meaningful dynamic may be the one between the government's occasional bouts of insularity and the public's seemingly insatiable curiosity about Western culture. "The media sometimes like to say that the Chinese prefer traditional things," said Leon Yang, the urban planner. "But we've had 5,000 years of history. Maybe we want something new."