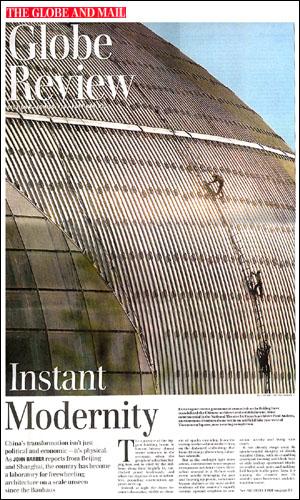

China's transformation isn't just political and economic -- it's physical. As JOHN BARBER reports from Beijing and Shanghai, the country has become a laboratory for freewheeling architecture on a scale unseen since the Bauhaus

China's transformation isn't just political and economic -- it's physical. As JOHN BARBER reports from Beijing and Shanghai, the country has become a laboratory for freewheeling architecture on a scale unseen since the Bauhaus

The epicentre of the biggest building boom in human history almost seems romantic in the evenings, when the people of suburban Beijing turn out to stroll by the millions along their brightly lit, car-choked grand boulevards, and when the daytime chaos of relentless, pounding construction appears to let up.

Indeed, at night the chaos becomes decorative, visible as showers of sparks cascading from the cutting torches of ironworkers busy on the darkened scaffoldings that loom 30 storeys above every suburban sidewalk.

But as the midnight light show attests, construction never stops or even pauses in China's cities. Here, urban renewal is a Richter-scale event, utterly destroying the past and heaving up proud, sometimes bizarre skylines as the most visible evidence of the country's equally seismic upward eruption in economic activity and living standards.

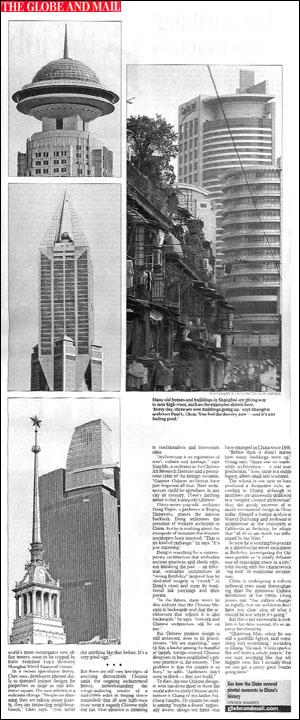

It has already swept away the quintessential imagery of dowdy socialist China, with its crumbling courtyard housing and bleak Soviet-style walkup apartment blocks, its walled work units and tinkling-bell bicycle traffic jams. Now, it is turning the country into the world's most boisterous architectural funhouse.

Not since its birth in the Bauhaus almost a century ago has the modern revolution raged as hot as it does in China today.

Shanghai's insatiable hunger for the new and shiny will soon add the world's tallest building, designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates of New York, to the city's showy skyline. In Beijing, the heirs to Mao have chosen avant-garde architecture to announce their country's renaissance, issuing a series of extravagant commissions for monuments that challenge the definition of buildable, especially the eye-popping megastructure designed by Dutch star architect Rem Koolhaas to house China's state broadcaster.

The word that foreign and local architects rely on most frequently to describe the working environment in China today is "paradise."

"China has become a living laboratory for some of the world's finest architects," says Beijing-based architect Adam Robarts, who argues that Shanghai, in particular, is the site of "the very finest buildings that are being built in the world right now."

China is "a big party for everybody," according to Karen Cvornyek, who heads the thriving Shanghai branch of Toronto-based Bregman + Hamann Architects (B+H). "There is just so much work."

A paradise of sorts, adds Chinese-Canadian architect Alfred Peng, an early entrant into the building frenzy and a prominent critic of Beijing's unrepentant embrace of the international avant-garde -- "a paradise for pioneers and for pirates." B+H was one of the first foreign design firms to mine China's riches, and its practice epitomizes the country's frantic activity. With giant state-owned architectural institutes churning out its working drawings like widgets, the 80-person Shanghai office designs two million square metres of new building annually -- twice as much as the total amount contained by all the high-rise buildings constructed every year in Canada's largest and busiest market, Greater Toronto.

B+H was one of the first foreign design firms to mine China's riches, and its practice epitomizes the country's frantic activity. With giant state-owned architectural institutes churning out its working drawings like widgets, the 80-person Shanghai office designs two million square metres of new building annually -- twice as much as the total amount contained by all the high-rise buildings constructed every year in Canada's largest and busiest market, Greater Toronto.

The firm is regularly asked to create detailed design proposals for projects twice as large as Montreal's Place Ville Marie in as little as three weeks, according to Cvornyek. Plans for new towns designed to accommodate tens of thousands of people emerge just as quickly.

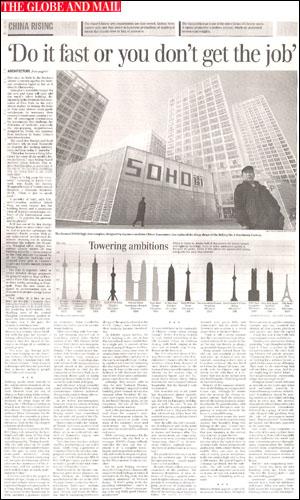

"You either do it fast, or you don't get the job," Cvornyek says, raising her voice to be heard above the pounding jackhammers and shrieking saws of the central Shanghai construction project to which the firm recently relocated. "Because that is the pace this country is moving at now."

Foreign architects especially are thriving in a country where breaking with the past has become a driving cultural force, led by a government that has turned to foreigners to design all its ambitious grands projets.

"Ten years ago, foreign architects were banging on the doors," says Robarts, who has lived in Beijing with his Canadian-born wife for almost 20 years. "Now, if you're a developer in China and you don't hire a foreign architect, people don't take you seriously."

Nothing speaks more directly to the ardent internationalism of the new Chinese entrepreneurs and their clientele than the city of chaste and gleaming white towers, called Jianwai SOHO, that recently replaced the dingy shops of the Beijing No. 1 Machinery Factory in what is now the city's central business district. Designed by Japanese architect Riken Yamamoto, the 20-tower high-rise ensemble is a bravura exercise in ultrahigh-density urbanism, built by the city's largest commercial developer.

Architecture is a passion for SOHO China Ltd., owned by the husband-and-wife team of Pan Shiyi and Zhang Xin, and the fever is spreading quickly. "Beijing is probably the only place in the world now where commercial developers have the guts to work with top avant-garde architects," Zhang says. "When we launch a new project, we make an enormous effort to advocate the importance of the architecture, and the architects we work with become instantly in demand in China."

A recent convert to the gospel of modern design, Zhang is a Beijing work-unit refugee whose escape to capitalism began with piecework at a Hong Kong factory and, before she returned to her hometown in 1995, included a graduate degree in economics from Cambridge University and a career in international banking.

After succeeding with Yamamoto, her company reached out to Iraqi-born radical Zaha Hadid, winner of the 2004 Pritzker Architecture Prize, for its next megaproject, a "logistics hub" in southeast Beijing. It has commissioned Australia's Lab Architecture Studio to design another large mixed-use complex in the exploding-glass style of Daniel Libeskind and won a special award at the prestigious Venice Biennale in 2002 for the Commune at the Great Wall, an architectural theme park of daring weekend houses built in the shadow of the wall north of Beijing.

And whenever a local journalist wants to know why SOHO so rarely commissions Chinese architects, Zhang tartly reminds them why nationalism is "so backwards."

As an ardent free-enterpriser, however, even she admits to being shocked by the extravagance of recent government commissions in Beijing, which have scandalized the set-aside old guard of the Chinese architectural establishment.

Most controversial is the National Theatre by French architect Paul Andreu, an enormous titanium dome set in an artificial lake just west of Tiananmen Square, now nearing completion. "You slap your own face and get swollen, pretending you are a rich man," scoffs Peng, a professor at Tsinghua University who has campaigned tirelessly against the project. "We have less than one-fifth of U.S. GDP per capita, yet they want to build a grand theatre four times the cost of Lincoln Center."

"You slap your own face and get swollen, pretending you are a rich man," scoffs Peng, a professor at Tsinghua University who has campaigned tirelessly against the project. "We have less than one-fifth of U.S. GDP per capita, yet they want to build a grand theatre four times the cost of Lincoln Center."

Undeterred by the theatre controversy, government planners are busy creating an architectural wonderland on the site of the 2008 Olympic Games, centred on the extraordinary "bird's nest" stadium designed by Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. And by embracing Koolhaas's design of the new headquarters for CCTV, China's state broadcaster, their audacity became breathtaking.

At 400,000 square metres, the CCTV building is the size of four Bay Street bank towers tumbled into a single pile. It consists of two towers leaning 10 degrees in different directions, rising more than 70 storeys from either end of an enormous, L-shaped base and joined at the top by an equally large, daringly cantilevered structure mirroring the dog-legged base. An engineering tour de force in the most stable bedrock, it will dominate the skyline of one of the most earthquake-prone capitals in the world.

Although they weren't able to stop the new National Theatre, critics of Beijing's imperial-scaled building plans claimed victory this summer when President Hu Jintao's new regime moved to simplify the lavish Olympic plans. In the meantime, the fate of the CCTV building remains unclear.

And as the government moves to cool down the country's overheated development industry by restricting access to credit, even some of the country's most avid modernizers are beginning to question the results of the national makeover.

While resisting nostalgia for the impoverished city she fled as a teenager, SOHO's Zhang willingly concedes the new city that replaced it is "a complete mess," largely undistinguished architecturally and fatally lacking in the planning controls that help to rationalize the Western cities it tries to emulate.

For his part, Beijing architect Yung Ho Chang detects historically unprecedented feelings of cultural inferiority in the big party and its "mindless imitation" of Western design. "If that's going to be the prevailing atmosphere -- and it is at the moment -- there's never going to be any really good Chinese architecture."

It's easy to believe in the continuity of Chinese culture when visiting Chang's Atelier Feichang Jianzhu in a tile-roofed outbuilding of the Old Summer Palace in northern Beijing, with birds singing in the trees and an unruly crop of sunflowers in the forecourt.

The U.S.-educated dean of Beijing University's new faculty of architecture, Chang is also the son of architect Zhang Kaiji, designer of such Maoist monuments as the National Museum of Revolutionary History on the eastern edge of Tiananmen Square and the National Guest House where Nikita Khrushchev once enjoyed Chinese hospitality. But the thread is only sentimental.

The beautiful city of his youth has disappeared almost entirely, Chang laments. "Even 15 years ago, the city had integrity and dignity as well," he says. "It was all grey, with green trees popping out -- and that was it. That was the city that attracted my father from the south 60 years ago, and that's how I remember it."

Now, he adds, the city's insensitive development and "really awful architecture" are ruining its appeal to visitors and business alike. The new monuments are impressive but meretricious, creating a city of "interesting objects" to demonstrate Chinese sophistication -- "the best of architecture in a Gucci bag."

But people don't live in a city like that, the architect says. "It's more like an exposition -- maybe a park. That's a real problem."

Recent reforms reflect some new awareness of the problem. The summary demolition of what remains of Beijing's ancient courtyard neighbourhoods is no longer permitted, according to Zhang Zugang, professor of architecture at Tianjin University and vice-president of the Architectural Society of China. He speaks hopefully of planned new green belts and promenades, but he admits that historical preservation is a novel proposition in the new China.

"There is still a strong opinion that the courtyard housing is dilapidated and not fit for people to live in," he says. And there is, as always, an insatiable hunger for the new.

Many people evicted from the old city and resettled in distant high-rises are delighted with the upgrade, according to Joe Carter, a Canadian architect who has lived in China for almost 20 years, currently with his Chinese wife and family on the 14th floor of a 25-storey high-rise in the instant new city bordering the Third Ring Road in eastern Beijing.

Reports of the rampant demolition of old Beijing are exaggerated, Carter says, although he admits that the pressure for change remains intense. And the preservation of old hutong (laneway neighbourhoods) by gentrification, with pop stars and foreigners now beginning to renovate beneath the trees, is a mixed blessing.

"Gentrification scours the inner and makes the shell a kind of status symbol, this beautiful thing that belongs to the past," Carter says. The multigenerational social life that gave meaning to the ancient city structure is gone forever.

Today's Beijingers live in a high-rise city where the typical street is six lanes wide, almost permanently gridlocked, with a fence down the middle. They can cross on foot only at widely spaced overpasses. Walls two metres high and as long as 500 metres, the typical length of a Beijing superblock, line the sidewalks. The old work-unit compounds inside may have given way to dozens of high-rise condominiums, but the forbidding walls remain.

Modern Beijing appears especially disastrous viewed from Shanghai, a city that was originally built by Westerners to be a globe-spanning entrep?t and has assumed the identity of 21st-century globalism with greater ease than the capital -- if only because it was built with conventional streets and blocks.

"You have to criticize the Beijing mentality," says Shanghai architect Paul L. Chen, a partner in HPA (Haipo Architects), the city's leading Chinese-led private practice. "Everything there is political. They are looking for a political fa?ade, a quick fix for a new image of Beijing. They want to do something that will just blow you away. And they are neglecting the urban fabric -- nice neighbourhoods, community, things that are tough to do."

Shanghai wasn't much different as recently as two years ago, when local authorities routinely informed laneway residents of imminent demolitions simply by posting notices on their doors ordering them to clear out. But protests throughout urban China induced a central-government clampdown, followed by a purge of local officials charged with profiting from the sale of government-owned land. Unprecedented limitations on heights and densities appeared at the same time.

One result, Chen complains, is that a lot of his projects have been reduced in scale or stalled as public officials undertake the novel and time-consuming process of negotiating compensation for families evicted from neighbourhoods of crumbling shikumen, Shanghai's distinctive Westernized version of the traditional Chinese courtyard house.

But he's not complaining overmuch. "Every day, there are new buildings going up," Chen says. "You feel the density now -- and it's not feeling good."

Enormous complexes crowd narrow streets built for rickshaws and trams. What was once farmland across the Huangpu River in Pudong is now a sterile but imposing showcase of some of the world's most extravagant new office towers, soon to be topped by Kohn Pedersen Fox's 95-storey Shanghai World Financial Centre.

In a recent speculative frenzy, Chen says, developers phoned daily to demand instant designs for properties as large as one kilometre square. The new sobriety is a welcome change. "People are planning, they are talking about quality, they are respecting neighbourhoods," Chen says. "They never did anything like that before. It's a very good sign."

But there are still very few signs of anything distinctively Chinese amid the ongoing architectural frenzy, notwithstanding the cringe-inducing results of a mid-1990s edict in Beijing (since rescinded) that all new high-rises must wear a vaguely Chinese-style red hat. That absence is irritating to traditionalists and innovators alike.

"Architecture is an expression of one's culture and heritage," says Xiao Mo, a professor at the Chinese Art Research Institute and a prominent critic of the foreign invasion. "Current Chinese architects have just forgotten all that. Their architecture could be anywhere, in any city or country. There's nothing about it that's uniquely Chinese."

Thirty-seven-year-old architect Dong Yugan, a professor at Beijing University, rejects the nativist backlash. Dong welcomes the presence of Western architects in China. But he is scathing about the stampede of imitation the Western interlopers have inspired. "That is no kind of exchange," he says. "It's just following."

Dong is searching for a contemporary architecture that embodies ancient practices and ideals without imitating the past -- an informal, utilitarian architecture of "strong flexibility" inspired less by tiled-roof imagery (a "crutch," in Dong's view) and more by traditional ink paintings and their poems.

"In the future, there won't be this attitude that the Chinese lifestyle is backwards and that the architecture that reflects it is also backwards," he says. "Western and Chinese architecture will be on par."

But Chinese modern design is still unknown, even to its practitioners. "We are searching," says Qi Xin, a leader among the handful of largely foreign-trained Chinese designers to have established a private practice in the country. "The problem is that the market is so busy," he adds. "Architects don't need to think -- they just build."

To date, the one Chinese designer who has done most to show the world a distinctively Chinese architecture is Chang of the Atelier Feichang Jianzhu. He counts his studio among "maybe a dozen" regionally aware, design-led firms that have emerged in China since 1999.

"Before then it didn't matter how many buildings went up," Chang says, "there was no worthwhile architecture -- it was pure production." Now, there is a visible legacy, albeit small and scattered.

The school is too new to have produced a distinctive style, according to Chang, although its members are universally dedicated to a "simpler, cleaner architecture" than the gaudy excesses of so much commercial design in China today. Himself a former acolyte of Marcel Duchamp and professor of architecture at the University of California at Berkeley, he admits that "all of us are much too influenced by the West."

So now he is steering his practice in a direction he never anticipated at Berkeley, investigating the Chinese garden as "a totally different way of organizing space in a city," even toying with the characteristic "big roof" of traditional architecture.

China is undergoing a cultural upheaval even more thoroughgoing than the notorious Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, Chang points out. "Our culture changes so rapidly that we architects don't have any clear idea of what it should be and where it's going."

But that's not necessarily a problem in his view; instead, it's an impetus for creativity.

"Chairman Mao, when he was still a guerrilla fighter, said something very interesting," according to Chang. "He said, 'A little spark of fire will burn a whole prairie.' I'm not sure anything like that will happen now, but I actually think we can get a pretty good bonfire going here."

Towering ambitions

China is home to almost half of the world's 20 tallest towers and high-rise buildings, most of which were constructed in the past 10 years. Some of the tallest are represented below, along with the date they opened.

CN Tower

Toronto

553 metres*

1975

Ostankino Tower

Moscow

537 metres*

1967

Taipei 101

Taipei, Taiwan

509 metres

2004

Oriental Pearl Tower

Shanghai

468 metres*

1995

Petronas Towers

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

452 metres

1998

Sears Tower

Chicago

442 metres

1974

Jin Mao Tower

Shanghai

421 metres

1998

Tianjin TV Tower

Tianjin

415 metres*

1991

Two International Finance

Hong Kong

415 metres

2003

Central Radio & TV Tower

Beijing

405 metres*

1995

CITIC Plaza

Guangzhou

391 metres

1997

Shun Hing Square

Shenzhen

384 metres

1996

Eiffel Tower

Paris

300 metres

1889

*Primarily used for communications