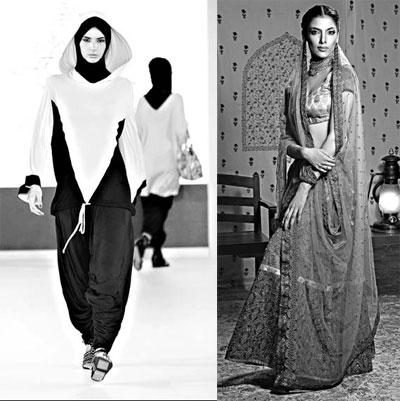

Women's clothing choices often must be weighed against

cultural expectations. An outfit by Dubaibased Rabia Z; right, a

sari by Anupama Dayal, a designer in New Delhi. Mifw & Sobol

Fashion Productions; Right, Anupama Dayal.

Women in India are opting for form-fitting business suits. In Sudan, a woman who dares to wear trousers is sent to jail. In the capitals of Europe, a Muslim head scarf becomes a political lightning rod. And across the Islamic world, new designers are nudging women to step out of fashion purdah with clothes that meld global catwalk trends with Muslim mores.

In old societies facing a flurry of Western goods and ideas, a woman often carries the competing demands of tradition and modernity on her back. How she dresses conveys a great deal more than her individual sense of style. She is evaluated by what she does or does not wear, whether it is by her parents, in-laws, co-workers, loutish men on the bus and even, as with the debate over the Islamic head scarf, by politicians.

Sometimes she conforms to tradition, sometimes she challenges it. Consider India today, where a decade of roaring economic growth has been accompanied by new opportunities for the urban, educated woman- and in turn, is offering her a vast menu of new looks.

"Almost every day I feel this country changes," said Anupama Dayal, a designer in New Delhi whose autumn collection features short dresses and floppy tunics. "And who changes the fastest? It's the woman."

As a woman earns more money, power and freedom, how she dresses often changes. But, more so than men, women find that their wardrobe choices are often calibrated by cultural expectations: modesty, authority, shifting ideals of femininity. What may connote tradition to a Westerner could telegraph a higher status to an Asian or African woman.

In Nigeria, for instance, a college student may wear skinny jeans or slinky dresses, but once she climbs the career ladder, a woman would rarely be seen in anything but customary Nigerian clothes, whose costliness and craft may be unclear to the Western eye.

Similarly in India, a young office worker today almost always wears trousers or suits. But a senior female manager would more likely choose a sari.

"I actually do think the sari makes me feel a lot more authoritative," said Ambika Nair, who has worked as a journalist and a lawyer and now runs the legal publishing arm of Thomson Reuters in India. "And I don't look at the sari or churidar as traditional, and I don't think wearing a suit, articularly an illfitting one, connotes modern."

The lives of Indian women are in a state of profound flux. Today, there are as many girls as boys enrolled in primary school. Women's share in the workplace has risen. Women increasingly live on their own, travel widely, adopt children as single mothers, and even divorce. All the while, they have to deal with entrenched social and religious customs, sexual harassment, and sometimes, outright violence.

In Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim country, the hijab, or jilbab as it is known there, is far more common than it was a generation ago. But now, it could be a designer scarf held in place with an eclectic brooch, or paired with a trendy sun visor.

"We look to the West for style and trends, and we modify them to suit our modest needs," said Liana Rosnita Redwan-Beer, a magazine editor in Jakarta.

The balance is particularly tricky for Muslim women living in the West. Rabia Zagarpur was living in California when she began dressing according to Islamic code 10 years ago. "There's the dilemma that 'Oh my God, that's a cute trend but I can't wear it,'" she said of her own experience. "It's depressing to shop. And then of course there's work. Corporate wear? What do you wear?"

Ms. Zagarpur, now based in Dubai, began designing clothes for women like herself: track suits with longer, torso-covering tops, bold printed silk caftans, even a one-piece hoodie hijab made of stretchable, breathable fabric.

"To me," Ms. Zagarpur insists, "being modest and chic is very compatible."

Chic seems not to have been the concern of Lubna Hussein in Sudan when she was arrested last year on charges of indecency for wearing trousers, a crime punishable under Sudan's version of Sharia law by 40 lashes. The court eventually spared the whip but imposed a fine of about $200. When Ms. Hussein refused to pay, it sent her to jail.In India, where society is churning rapidly, women are required to make delicate choices all the time.

Suhasini Haidar, a TV anchor, wears a tailored blazer on air. But she knows that for an official government dinner, she must drape on a sari. "There are several places," she says, "where it would be rude to show up in Western clothes."

For Ms. Dayal, the sari is reserved for moments of reckoning. "When I most need my self-confidence, I must wear a sari," she says. "When I can take no risks, I must wear the sari - despite having Armanis and Guccis and hundreds of Anupamas in my wardrobe."