A US property agent draws potential Chinese customers with promises of green cards at a real estate fair in Beijing in this file picture taken in late June. Wu Changqing / for China Daily

For many of China's wealthy, investing $500,000 in a US government program is the best way to obtain a green card - for them or their children. Duan Yan reports from Beijing.

Yvonne Liu, 22, wanted to stay in the United States after her university studies, and her mother, a 46-year-old wealthy Chinese businesswoman, figured out a way to make that happen.

Lily Zhang flew to the US to look for investment opportunities. Her plan was to move some of her international trade business from the city of Xiamen in southern China to southern California.

She has registered a branch of her company in the US, which is a way for her daughter to stay in the West after her studies at the University of Missouri at Columbia. (Zhang would not give their real names because her project is still ongoing.)

"When it grows bigger, I can give this part of the business to my daughter," Zhang said.

According to statistics from the US Department of State, the number of so-called "investor green cards" issued to non-Americans nearly tripled to 4,218 in the 2009 fiscal year. About 1,800 of those recipients are from the Chinese mainland. South Korea is second with 903 recipients.

In comparison, just 1,443 investor visas, referred to as EB-5 visas, were issued in fiscal year 2008.

The real estate price hike and stock market boom in China has enabled the rich to spend lots of money for their American dreams. And many of them, like Zhang, are doing this for their children.

After two years of planning, Zhang's company, which makes paper out of limestone, will be an operational company in the US within six months.

"It will create at least 700 jobs for locals," Zhang said. With California's unemployment rate of over 12 percent, she found it an ideal time to invest in an American dream for her daughter, and she is willing to pay big money for it.

The $70 million investment partly comes from her pocket, as well as bank loans. Another one third of it comes from 50 EB-5 investor visas that can help 50 other Chinese wealthy people who can pay a minimum of $500,000 for permanent residency in the US. These EB-5 quotas could help her raise $25 million for her company.

Other people who own companies like Zhang's are trying to raise money from wealthy investors who want to get a green card. Regional centers, which refer to high-unemployment areas designated by the US Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), are also eligible to receive immigrant investor money.

The number of approved regional centers has surged. In January 2009, only 30 EB-5 regional centers existed, but as of July 2010, 100 regional centers had been approved by USCIS.

The first to notice the surge of Chinese applicants for investor green cards was the lawyers who specialize in visa applications. At his law office in City of Industry, California, immigration attorney David Fang took his first investment immigration case for a client from Taiwan when the program was authorized in 1992.

At that time, the investment was $1 million. Now the minimum is $500,000.

Ten years ago, 70 percent of his clients were from Taiwan and the rest were from Hong Kong. "Now, 70 percent of them are from the Chinese mainland," Fang said.

The US life

Adjusting to life in the US does not seem to be a problem for Lily Zhang and her husband, who can read and converse in basic English. "You don't need that much English for daily life," she said. And as for the business, she has hired a translator to help.

Now more than 1.1 million Chinese Americans live in California, according to the US Census Bureau's 2008 American Community Survey.

At her law office in Chinatown, New York, Yang Fuhao has seen a decline in H-1B work visa applications from Chinese, but has received more inquiries about investor visas. New to the business of investment immigration, she is now representing three clients in that capacity. "All of them are from the Chinese mainland," Yang said.

Contrary to the new boom in investment immigration for the Chinese mainlanders, many Chinese graduates of US universities faced difficulties finding a job in the US, and many decided to go back to China. The number of H-1B work visas for Chinese citizens dropped from 16,628 in fiscal year 2007 to 12,922 in fiscal year 2009, according to statistics from the US Department of Homeland Security.

For Zhang, that's exactly one of the reasons that she invested in the US for her daughter Yvonne. During the economic downturn, a green card for her daughter will make sure that she won't face the same job-hunting difficulties many of her classmates and friends faced.

"You just don't know what will happen to the immigration law if and when a new president is elected. And all the good jobs are saved for US citizens and green card holders," Zhang said.

Less pressure

Yvonne Liu is studying economics and business management at the University of Missouri at Columbia, and will graduate next summer. She liked her studies in the US because she has less pressure there.

"No one will keep their eyes on me or give me too much pressure. I can do whatever I want," she said.

She joined a popular music band in school with some of her friends. "And I don't need to worry about my parents when they grow old because the social welfare system here is better. "

She doesn't have to compete with more than 9 million Chinese students in the national college entrance exam.

"The US college application process is more personalized," she said.

Liu appreciates what her parents have done for her.

"Many of my (Chinese) friends in school wanted to stay in the United States, but there are many difficulties. I'm really lucky that I don't have the same worries because my parents are very capable."

Selling the program

In Beijing, wealthy parents like Cao Zhenghe went to information sessions and promotions for US investor immigration programs, looking for opportunities that can help their children have a better future in the United States.

"Are you also here for your kid?" Cao asked a middle-aged woman who sat next to him during an information session. She nodded yes. During two days of information sessions for investment immigration projects, Cao met several parents who had already sent their children to study in the United States.

"We don't chat a lot with each other, you know, because of privacy concerns," Cao said.

For many wealthy Chinese, investing $500,000 into a US government designated regional center program is one of the most convenient ways to reach their American dream, or for their kids.

Cao, 45, came to Beijing on June 10 and went to a session hosted by Beijing Worldway Immigration Service Co, to learn about a regional center program about a gold mine in Idaho. He flipped through the brochure and jotted down notes and questions as immigration consultants and representatives from regional centers continued to sell him on the project.

Although he was told that his money will be safe and he can buy out his investment after five years, Cao knows that many of these projects bear a certain risk. He is finding it difficult to choose the right one. "I'm getting tired of these meetings now," Cao said.

As an owner of an iron mine in Hebei province, Cao understands the mining business more than most of the participants. But he doesn't really understand how the business is running in the United States, and doesn't have relatives in the US except for his 21-year-old son who is currently studying in California.

"The first generation of immigrants is not going to be easy. But when he has his own family, life will be better for his children," Cao said.

He is determined to support his son's decision to get a green card.

"I don't know what he is studying there; he is quite independent and finished the college application all by himself," Cao said.

Immigration Lawyer David Fang warns that most centers haven't been operating long enough to complete their projects or establish an investment track record. He fears that many projects marketed to investors "won't be successful in terms of job creation, and investors will be unable to get their money back, or even lose their green card."

Risky dreams

Even if they can afford it, not everyone is so sure that they can realize their American dream.

The $500,000 investment is only enough to pay for 10 workers' salaries for one year.

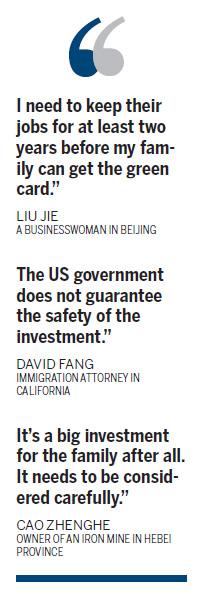

"I need to keep their jobs for at least two years before my family can get the green card," said Liu Jie, a businesswoman in Beijing whose biggest concern about choosing an EB-5 regional center program is whether she can get her permanent green card.

To succeed, her investment needs to secure 10 jobs for locals in a region with a high unemployment rate for at least two years before her conditional green card can become a permanent green card. And the business has to be profitable so that she can get her money back after five years.

In the promotions and brochures, immigration consultants, lawyers and representatives from regional centers carefully paint a rosy picture to their clients, most of whom are unfamiliar with US investment. They avoid talking about any risk or any negatives.

"Regional centers tend to oversimplify the process of investment immigration," Fang said. "And immigration agencies in the Chinese mainland are also new to the investment immigration themselves."

Some consultants at the sessions like to say that the risk is minimal because the program is backed by the US government, but Fang warns that this statement is an exaggeration. The US government does not guarantee the safety of the investment, he said.

Those wishing to join the EB-5 program will need minimum assets of at least 10 million yuan ($1.48 million) Zhao Jiangcheng, an immigration consultant of Beijing Worldway Immigration Service Co., told the prospective clients who were hesitating.

"The worst-case scenario is that even if the investment fails, your life will not be affected severely," he said.

Most of the investors are quite wealthy and $500,000 represents only a small portion of their wealth. Liu Jie, for example, said she would sell a few apartments to pay for her part of the investment immigration program.

Many of her friends went to study in the United States in the 1990s and stayed there after graduation. One of her friends is a research fellow in the United States, "but I don't want to stay in the lab every day like her," Liu said.

When the real estate prices began to drop slowly in Beijing, she decided to give up her American dream.

"I don't know what to do there," she said.

For Cao Zhenghe, who is determined to make an investment for a green card, the American dream is a bit different. He doesn't want his son to be an American citizen because a green card would be better for family business in the future.

"What if he came back to do business in China? I can't help him get a Chinese green card if he became an American."

Cao is trying to find Chinese people who succeeded in getting their permanent green cards and got their investment back after five years, but so far, he has been unable to find them.

He would love a piece of America for his family and for his business, but wants to be smart about venturing into this.

"It's a big investment for the family after all," he said. "It needs to be considered carefully."