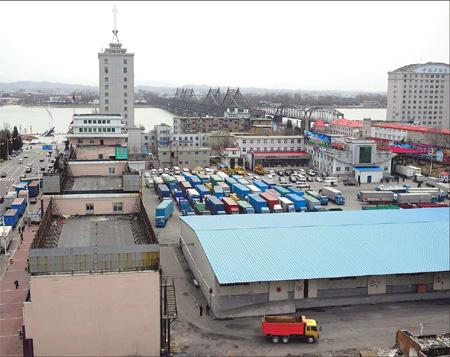

Trucks line up as they wait to go through the port at Dandong, Liaoning province. The border trade between China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea is booming in this coastal city. [Feng Yongbin and Chen Hao / China Daily]

Trucks line up as they wait to go through the port at Dandong, Liaoning province. The border trade between China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea is booming in this coastal city. [Feng Yongbin and Chen Hao / China Daily]

It was early in the morning, and like most retailers in Dandong, Liaoning province, Sun was busily packing up mountains of goods to send to her customers in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

"The day after tomorrow is a birthday celebration of their late leader Kim Il-sung," Sun (she declined to give her first name) said in April as she piled bread, watermelons and other food into boxes. "I received orders for more than 100,000 yuan ($14,000) last week.

"Koreans like big festivals because food, clothes and other necessities will be given out," she said.

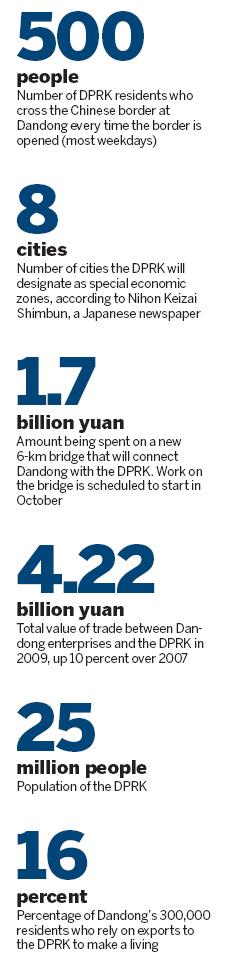

More than 500 people from the DPRK arrive in Dandong to stock up on vital supplies every time the border is opened during weekdays and stores here are already doing roaring trade.

However, Chinese retailers predict even better times after news that officials in Pyongyang plan to open up more cities to outside investment.

According to reports last month by Nihon Keizai Shimbun, a Japanese newspaper, the DPRK will designate eight cities - including the capital Pyongyang and Chongjin - as special economic zones. It is one of the biggest moves by the reclusive nation to open up since Rajin, a port neighboring Huichun in Jilin province, was given the status in 1991.

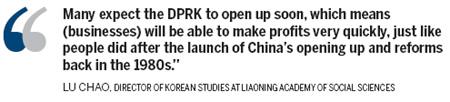

The move is part of the DPRK's desire to attract as much foreign capital as possible to aid its economic development, said Lu Chao, director of Korean studies at Liaoning Academy of Social Sciences.

Following the currency reform last year, analysts say the DPRK leadership is forging ahead with the opening up process. The country is now in talks to rent two islets to Chinese enterprises for commercial use over the next 50 years.

For the growing number of traders in Dandong, the move could bring even more business their way.

"Many expect the DPRK to open up soon, which means (businesses) will be able to make profits very quickly, just like people did after the launch of China's opening up and reforms back in the 1980s," said Lu, who believes the new zones will reinvigorate the domestic market and lead to a sharp rise in the demand for imported goods.

"Border trade is good for both countries, so it should be encouraged," he said.

Future Chinese investors will likely open bases in Dandong and one, if not several, of the DPRK's special economic zones, he predicted, adding that they will eye long-term profits rather than simply concentrate on short-term opportunities.

Plans have already been unveiled for an international trade and commerce center in Dandong, as well as for a second bridge to link China with the DPRK across the Yalu River. Work on the 1.7-billion-yuan, 6-km crossing, which will connect with the Trans-Siberian Railway, will begin in October and is expected to take three years to complete.

"Dandong will serve as the hub of bilateral ties in trade, investment and tourism," said Zhao Liansheng, the city's mayor.

Official statistics show more than 70 percent of bilateral trade between the two countries is handled in Dandong. The trade with the DPRK was worth more than 4.22 billion yuan last year, up by 10 percent over 2007, show figures from the city's foreign trade and economic cooperation bureau.

No cash on delivery

Shiwei Street, just behind the city's customs offices, is known locally as "Korean Street" for its abundance of stores catering to customers sent from the DPRK. Although there is no official figure on exactly how many there are, China Daily reporters witnessed at least 50 retailers loading goods onto trucks when they visited the street in April.

Sun, a tall but thin woman in her 50s, has run a business here for about 10 years. Shelves in her modest, 20-square-meter store are lined with goods ranging from fizzy drinks and chewing gum to socks and gas cookers.

Her success is not purely due to the variety of products she offers. Her guangxi, or good connections, have also helped.

One of her most regular customers is an official from the DPRK's Ministry of State Security, whom Sun was introduced to by relatives working in the city's immigration inspection unit. This relationship means her store can make up to 80,000 yuan a year.

A retailer loads boxes of fruit and vegetables ready to be sent to customers in the DPRK.

A retailer loads boxes of fruit and vegetables ready to be sent to customers in the DPRK.

Yet one thing remains a major concern for traders on the Korean Street: The risk of not getting paid.

The DPRK's purchasing officials often pay for goods after they are shipped out but retailers say they have no idea if an official will suddenly be called back to the country. Often officials are not even informed before their recall.

A storeowner who did not want to be identified said that, several years ago, he received an order for 100 tons of wheat flour but was unable to find the official who placed it after he sent it across the border.

However, most retailers argued this is an extreme case and generally there has been few problems with payment.

"Trust is crucial here," stressed Sun, who said the officials she deals with are usually on three-year rotations. "Although, the (DPRK's) staff rotation system can be problematic."

The key to a stable partnership is to make friends with the customers, she said, adding that the people she trades with "always tell me who will pay for the goods, no matter who stays or is called away".

Businesses dealing in larger commodities, such as building materials, are more cautious, however.

At the city's Haixin Metal Company, a clerk named Zhang said her company only ships its products once the buyer - mostly Koreans - has either paid in cash or through a bank transfer.

However, she added that trade with the DPRK was becoming harder because of the amount of "intelligence work" being carried out in Dandong is driving down prices.

A source who did not want to be identified said Pyongyang has sent dozens of people whose job is to find out the factory cost of products, information that would give the country's purchasing agents an advantage when it came to negotiating prices with suppliers.

"They come for two or three years and then just disappear back to their own country," said the source.

To maintain a stable relationship with its Korean customers, Zhang said Haixin Metal only ever quotes its rock-bottom prices.

The DPRK consulate general in Shenyang, capital of Liaoning, did not respond to China Daily's requests for a comment.

Profit margins have also been squeezed by the increased competition that has inevitably come with the rise in demand in the DPRK. An accountant named Wang at Haixin Metal said although the business brings in more than 10 million yuan, its net profit has fallen to just 100,000 yuan.

"If we ask for even an extra 50 yuan per ton of rolled steel plate, officials from the DPRK will drop us because they have many options to pay less," said Zhang.

Fierce competition has, however, increased the need for good service, say retailers, who often load the goods on to trucks themselves and will try to ship ahead of schedule.

"Many people are getting into the export industry in Dandong and are waiting for the opportunity when the DPRK finally opens up," said Zhang.

There is no official figure on how many of the 300,000 or so who live in Dandong rely on exports to the DPRK - a country of roughly 25 million - to make a living, but retailers suggested it was about 16 percent.

Exchanges between China and its neighbor have risen dramatically in recent times. Most electrical devices used in the DPRK, such as refrigerators and air-conditioners, were made in China.

In total, 300 vehicles carrying goods and tourists crossed the China-DPRK border last year - 220 from China, 80 from the DPRK, said Ma Gengsheng, chief of staff at Dandong Frontier Defense Inspection Station. In 1990, just two cars crossed into China from the DPRK.

However, despite the increased trade, investing in the DPRK still offers huge risks, said Wang Tingge, president of Huashang International Investment in Dandong.

"It's essential to do the research," he said. "We deal in projects worth more than $100,000 every day. In each case, we have to get guarantees for our clients from the DPRK that any policy related to a project they are investing in will not change. If it does, projects could be doomed to failure."

More cover stories