Academic says US has had its punchbowl taken away from it

BEIJING - Barely a week goes by when one UK academic or another passes through Beijing in an attempt to persuade Chinese students to sign up for further education at their institution. Given that one in five people alive in the world today live in China and that, therefore, one in five geniuses are presumably Chinese, it is no surprise they find it fertile hunting ground.

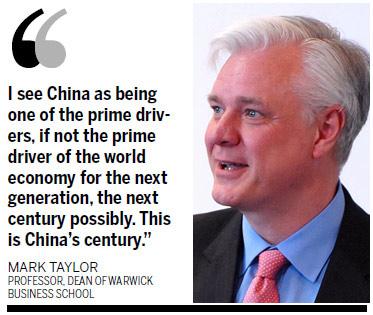

The latest questing scholar was Professor Mark Taylor, a leading international authority in open economy macroeconomics and international finance and dean at Warwick Business School.

His stated aim for the school is "to become Europe's leading university-based business school" with a mission "to create and disseminate world-class, cutting-edge research that is relevant in the sense of influencing organizations in the way business is done; to create world-class business leaders who are responsive to change and innovation whatever the size of the organization; to provide a return on investment for students and alumni and inform the way they think over their entire careers".

This is big talk from a big man both physically and academically. Taylor, 52, previously held chairs at City University Business School in London, at Liverpool University and at Dundee University, and has been a visiting professor at New York University. He was also a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, for five years and an economist at the Bank of England, and began his career as a foreign exchange dealer in the City of London.

Although his research interests are broad, he has a particular interest in empirical work on exchange rates and has made a number of important contributions in this area. He has most recently published work on the presence of non-linearity in real and nominal exchange rate movements and on the effectiveness of official foreign exchange market intervention. All this, of course, means that when he talks about China, his views are worth listening to. So what has he got to say?

"I see China as being one of the prime drivers, if not the prime driver of the world economy for the next generation, the next century possibly. This is China's century," he said in a recent interview.

"The consumer price index (CPI) came in at 4.4 percent in October. I don't think it's a great cause for concern because if you analyze those figures, most of the rise was in food prices. Chinese agricultural prices are still low by international standards so you would expect to see some redress in that area. And also there has to be some kind of redistribution of income towards farmers. So raising food prices is actually a good sign of redistributing income to farmers. Four-point-four percent growth in CPI against 9.6 percent growth in GDP is not that alarming. Also it's not that worrying because consumer demand is relatively weak in China."

But what of the future?

"China should think very hard about how it restructures its economy. The yuan has already revalued by about 2 percent since they abolished the peg. I would have thought a 2 to 3 percent revaluation over the next two to three years (would be ideal). And if in that period the economy could be restructured toward less reliance on export industries so there is an orderly transition, I think that would be a reasonable thing to do. Anything more than 4 percent would seriously damage the export industry of China, and why should China do that?

"I think it is in America's self interest to push for a rise in the yuan. There is a global interest in addressing these imbalances but I think it is more of a medium-term adjustment rather than a short-term adjustment. China I think ought to think of a readjustment over three to five years rather than the next one to two years so they can restructure their economy, move reliance away from exporting industries, perhaps try to boost consumer demand at home. You could think about competing more on quality rather than on price. You shouldn't worry too much about losing your export share if you are growing your own domestic economy.

"I think China's growth is sustainable for at least a generation or so. If you are talking about inflation of around 4.4 percent, growth of around 9 percent, that gives real growth of around 5 percent per annum. At that rate it would take 25 years to get to a comparable rate of GDP per capita of western economies, so I don't see any problem of growing at that rate for the foreseeable future.

"China's done extremely well in terms of its liberalization. If you contrast China with Russia, where there has been a complete free-for-all liberalization where you have this vast disparity in income and equality in Russia, China is very keen it doesn't make those mistakes," he said.

"Having a powerful and benign government certainly helps" in redistributing wealth, he added. "I think that's why China has done very well. They are right to be cautious on the speed, especially if you think about Russia: That's a salutary lesson in how not to liberalize. I think America has had the punchbowl taken away and wants everyone else to share in their hangover. There are some hard choices. There is a period of retrenchment taking place in the West and China can help redress that to some extent. But China should think about what is best for its own economy. Not single-mindedly but in terms of cooperating: A slow cooperation, a slow adjustment over the next three to five years, a slow restructuring is important. America has been the dominant global power for so long it is hard for them to come to terms with the new kid on the block."

As income is redistributed, as wages rise, the Chinese won't be able to compete on price alone. They will have to compete on quality, he said.

One product of Warwick Business School (WBS) is Tao Wang, now vice-president of 51job Inc, a leading human resource solutions provider in Beijing that serves domestic and multinational corporate clients through 26 offices in Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland.

Tao joined the business in April 2000 when it was a start-up company at the beginning of the Internet boom in China. He went to WBS in 1993, only the second MBA from the Chinese mainland to study there.

"With my first degree in mathematics and my second in engineering, I came to WBS with limited knowledge of business, finance or strategic thinking," he told an alumni newsletter. "When I began my studies, no one in China had really heard of Warwick or WBS. Since then I have been amazed how perceptions have changed. Now if people think about studying in the UK they know about Warwick To come to a brand new country to stay for a year to study was a real challenge. Although I was very confident about my learning abilities, I was somewhat nervous anyway and when I registered in the school, almost everyone I met informed me that the MBA in WBS was a very tough program. But I survived and studying at WBS was one of the most valuable experiences I have ever had. I loved the people and the experiences I had there and would not have missed it for anything."