China boasts more billionaires than anywhere else in the world, according to the 2010 China Rich List.

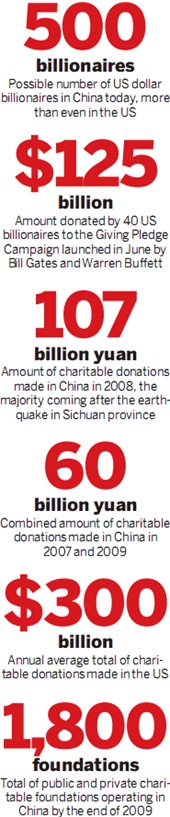

The de facto who's who of Chinese business, which is compiled and analyzed by Hurun Report, puts the number of people with a wealth of $1 billion or more at "between 400 and 500", surpassing even the United States.

Yet, the big question today is not about the size of their wallets but the size of their hearts - and whether China's superrich can measure up to Western philanthropic standards?

Although recent high-profile donations suggest the answer might be yes, some billionaires, or yiwan fuweng, still argue it is their duty to amass more money for themselves before they give it away to others.

About 50 of the country's wealthiest were used as a litmus test of China's generosity on Sept 29, when American billionaire philanthropists Bill Gates and Warren Buffett hosted a charity dinner in Beijing.

Before arriving, the duo had successfully convinced 40 US billionaires to donate at least half of their wealth - as much as $125 billion - under the Giving Pledge Campaign launched in June.

Despite widespread media speculation that some Chinese tycoons avoided the Beijing dinner because they feared being pressured to donate, Gates and Buffett said in a news conference afterward that more than two-thirds of those who were invited attended.

In fact, they went on to tell reporters that wealthy Chinese have "no reluctance" in talking about philanthropy. "I was amazed, really, at how similar the questions and discussions and all that was to the dinners we had in the US," Buffett told the New York Times after returning stateside. "The same motivations tend to exist. The mechanism for manifesting those motivations may differ from country to country."

Chen Guangbiao, chairman of Jiangsu Huangpu Renewable Resources Utilization, was the first in China to respond to the philanthropic call sent out by Gates and Buffett this year.

In an open letter to the pair posted on his company's website on Sept 5, Chen, who is 406th on the latest China Rich List, pledged that every penny of his fortune - approximately 5 billion yuan ($752 million) - will go to charity after his death.

He was followed by Feng Jun, president of Beijing Aigo Digital Technology, who pledged to donate everything to worthy causes before he dies.

Sharing the wealth

All-out donation is nothing new in China. In April this year, Yu Pengnian, an 88-year-old hotelier and real estate entrepreneur in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, gave 8.2 billion yuan in assets to a charitable foundation he set up.

Yet, such cases are still rare in a country where the elite has arisen almost entirely from nothing over the last 30 years. In China, philanthropy still takes a back seat to the pursuit of wealth.

Many Chinese entrepreneurs, including Zong Qinghou, chairman and chief executive of China's leading beverage maker, Wahaha Group, and No 1 on this year's Hurun Report rich list, openly argue that accumulating larger fortunes is more important, as it helps raise the country's employment rate and fosters economic growth.

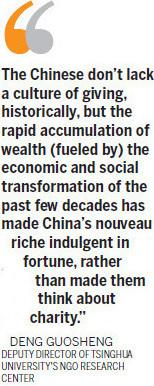

"Although China ranks as the world's largest luxury market, among many other areas, philanthropy is still a young sector here," said Deng Guosheng, deputy director of Tsinghua University's Non-Governmental Organization Research Center.

In China, the combined total of donations made in 2007 and 2009 was roughly 60 billion yuan. In the US, where per capita GDP is 10 times more than that of China, charities receive an annual average of $300 billion.

"The Chinese don't lack a culture of giving, historically," explained Deng, "but the rapid accumulation of wealth (fueled by) the economic and social transformation of the past few decades has made China's nouveau riche indulgent in fortune, rather than made them think about charity."

Wealthy people are also less willing to donate for fear of being pushed into the media spotlight and having their motives questioned, he added.

Many of the rich and famous in China have been scrutinized despite their proclaimed good intentions.

Chen once sparked controversy when he stood behind a wall of bank notes to announce his charity trip to poor rural areas in western regions of China.

He later said the move was designed to put pressure on others and spearhead a change in values.

"With the widening gap between rich and poor, China's wealthy class has become resented and, in many cases, misunderstood," said Deng. "If they don't donate, they are considered indifferent; if they give money away, there must be a selfish motive behind it.

"How can that social mentality encourage philanthropy?" he asked.

Ultimately, China has yet to build a healthy environment for charity, one that fosters an active and reputable community of foundations that can act as a platform for the rich and general public to help people in need, say experts.

Although there are no specific laws or regulations banning the establishment of public foundations, in practice most applications fail unless the organization is affiliated with a government department.

Those that actually acquire support from an authority and get the green light to collect donations are subject to official expropriation and tend to lose credibility with the public, said Deng.Examples abound of public foundations falling short of expectation and even being found to be involved in corruption.

Three months after the massive earthquake hit Yushu, a Tibetan autonomous prefecture in Qinghai province, last April, five government departments jointly issued a circular requiring all public foundations to pass on donations to the provincial government for "better and more efficient distribution of disaster relief funds".

The circular specified the use, management, distribution, supervision and reporting of the funds.

Despite the document's clarity, the move triggered a heated debate in the charity sector, with many arguing that authorities "should not intervene in the operation of charity foundations", as it would be difficult to effectively supervise the flow of money.

Shenzhen entrepreneur Yu said he also learned hard lessons some years ago when he found that ambulances he donated to several hospitals in inland provinces had been converted into sedans to chauffeur government officials.

"Very few of China's growing number of charity organizations and foundations tell donors where their money has gone.

"It's easy for local authorities to take advantage of that," said Yu.

Deng agreed and added: "It's not that the wealthy don't want to donate money, they just don't believe in the independence of public foundations in China, which have long been blamed for a lack of transparency and efficiency."

Efforts to operate independent of government agencies is also difficult, such as is the case with the One Foundation, which was launched in 2007 by Chinese movie star Li Lianjie - known in the West as Jet Li - as a project attached to the Red Cross Society of China.

In an interview last month with China Central Television, the State broadcaster, Li said the One Foundation - so called because of the idea that everyone can afford to donate 1 yuan every month - had hit a bottleneck in its development as it could not get approval to register as a public foundation.

The charitable group could be heading for a premature end, Li warned, explaining that once its three-year contract with the Red Cross expires it will be prevented from direct public fundraising.

Even though it is affiliated with the Red Cross, Li said the One Foundation still does not enjoy the full rights to use the donations it receives, and is also hindered by other restrictions.

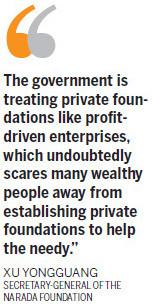

"Philanthropy must overcome the institutional challenges in order to mature," said Xu Yongguang, secretary-general of the Narada Foundation, a private organization sponsored by Shanghai Narada Group that is committed to public welfare projects.

Meanwhile, China's tax system also works against the development of philanthropic practices, Xu said. As a private foundation, Narada pays income tax if its fund makes a gain, perhaps from an investment, said the secretary-general.

Meanwhile, a company donor is only entitled to a maximum tax reduction equal to 12 percent of its annual profits if the money is not given to a government-backed public foundation, the number of which is very few.

"The government is treating private foundations like profit-driven enterprises, which undoubtedly scares many wealthy people away from establishing private foundations to help the needy," said Xu, who also claimed the lack of professional talents had resulted in most charitable foundations in China being highly inefficient.

China has only 1,000 public foundations and about 800 private ones, according to official statistics released at the end of last year. The latter has been developing at a fast rate in recent years, said Xu, who urged the government to take the opportunity by tapping further into the private capital of the wealthy class. China also lacks inheritance tax to push the rich to do the good, he added.

For Deng, the country still needs to mobilize the general public if philanthropy is going to mature.

Almost 60 percent of donations in China come from businesses or the wealthy elite (there is much overlap between personal and corporate philanthropy), while in the US more than 70 percent comes from the public, said the professor.

"We should realize that philanthropy is not a privilege of the rich but the responsibility of all," added Deng. "Charity is not just about giving your money away - it can be in the form of any voluntary work, however small."