The "coffee forest", skirting half of Zhukula village, Bingchuan county in Yunnan province, produces the best brew of Arabica. [China Daily]

The remote village of Zhukula in Yunnan was where coffee was first introduced in 1892, and it's still the best brew of Arabica you can find.

It's 5 am - time for Zhukula's villagers to get up.

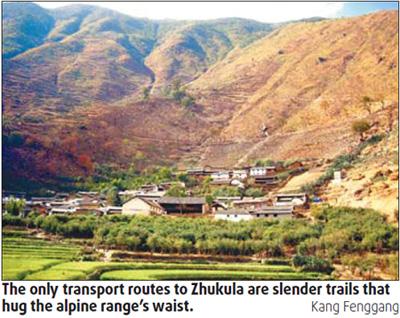

The inhabitants of this remote hamlet in Yunnan province have many mountains to climb before arriving at Pingchuan township's farmers' market around noon.

Because no road penetrates the mountains that seclude the settlement, the ethnically Yi farmers must lug their wares on their shoulders or sling them across horses' backs. The only transport routes are slender trails that hug the alpine range's waist.

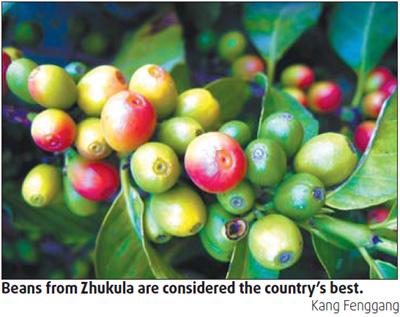

Their sacks are lumpy with walnuts and the beans of China's oldest coffee fields, recognized by the industry as the country's best.

"Coffee is to us what tea is to other Chinese," Zhukula's Party chief Qi Fenghua says.

It was through Zhukula that coffee entered China in 1892, when a French missionary left Vietnam to settle in the isolated village. Around the adobe church he built, he planted the seeds of his favorite brewed beverage.

It's unlikely he had any inkling these magic beans would grow to connect the tiny remote village to the country's giant coffee industry.

A Yi villager picks coffee beans in Zhukula. [China Daily]

The world's fastest growing market for the beverage still shares an umbilical connection to the place where the first beans were planted, despite its remoteness. Zhukula's coffee is bought by huge multinationals, such as Starbucks, Carrefour Group and Nestle. Its main purchaser is one of China's biggest coffee companies, Dehong Hogu Yunnan Coffee Co Ltd.

"Not only selling but also drinking coffee is entrenched in the lifestyle here," Qi says. "Every family does it."

Zhukula is home to 327 people from 83 households. Its dwellings are arranged like a throw of dice tumbling down a mountainside. All inhabitants are ethnically Yi, besides one Han.

Qi says the village's average per-capita annual income hovers around 6,000 yuan ($878), and mostly comes from selling coffee and walnuts, and working as migrant laborers.

The far-flung settlement is devoid of many modern amenities, like televisions. So, residents harvest, grind and boil their coffee harvests by hand.

Like most of Zhukula's clans, the family of 84-year-old Li Fusheng has grown, traded and imbibed coffee for four generations. His family of five tends 40 trees covering a 5.33-sq-km plot. Each tree produces about 5 kg of berries.

"Coffee has long been a part of life and who we are," Li says, while sipping a home-brewed cup in a courtyard home. He says most villagers drink about four cups a day.

Age has turned his voice into a croak and made his body seem to cave in on itself. He is one of the few residents old enough to remember the missionaries.

"There were three of them," Li recalls. "One drowned in 1949, while the other two returned to France after Binchuan county was liberated in 1950."

The settlement remains predominantly Christian, although the church building is an empty husk outside the balcony, where a few rows of wooden desks and benches are lined up in front of a blackboard - a classroom installed last year.

The first coffee tree the missionary planted died in 1997. But the rest of the 24 saplings still stand.

They proliferated because Zhukula's soil and climatic conditions are some of the world's most ideal for coffee cultivation. Today, the 1,370 trees of the "coffee forest" spread across 6.6 hectares, skirting half of the village.

Last year, they produced more than 4 tons of beans.

Their trunks and branches buttress a leafy ceiling bejeweled with clumps of red coffee berries. Three small children play among the trees. Nearby, an older boy peeks down through openings in the canopy.

Deeper in, a woman teeters on a ladder as she strips limbs of their ripe berries, causing the boughs to shiver. She drops handfuls of the ruby fruit into the reed basket lashed to her back.

But while coffee seems steeped into all dimensions of life in Zhukula, there is more money to be made from growing walnuts. Despite its celebrated quality and history, Zhukula's coffee sells for 4 yuan a kg, while walnuts bring in 27 to 30 yuan a kg.

"Because walnuts sell for so much more in the market, my family relies on them as our primary income source, while coffee provides extra money," 52-year-old Li Shuhua says.

Li's family of six owns more than 50 walnut trees, generating a total annual income of 30,000 yuan ($4,400), to which their coffee sales add 5,000 yuan a year.

The farmer vends his coffee to Hogu, which buys nearly all of Zhukula's beans, the company's general secretary Li Gongqin says.

"Zhukula's Arabica coffee is aromatic but not bitter, rich but not too strong," he says.

Last year, the company named the village "the source of Hogu coffee" and became its No 1 purchaser. It also provides 100 yuan in compensation to each household for conserving the "forest" as the birthplace of China's burgeoning coffee industry.

The country is the beverage's fastest growing market, and domestic consumption has increased by about 25 percent annually for the past several years.

Li doesn't expect the momentum to slow in the near future. "If we look 10 years ahead, China will probably cultivate about 1 million mu (1 mu is 1/15th of a hectare) of coffee," he says.

Since the first seedlings were planted in Zhukula, China's coffee trees have multiplied to cover 430,000 mu, about 40,000 of which were planted last year, Li says. Aside from 1,000 mu of the robusta variety grown in Hainan, the rest of the country's coffee comes from Yunnan, Li says.

He believes Chinese coffee could continue to grow in international acclaim, as many traditional production bases, such as Brazil, reduce output of the world's second-most traded commodity.

If so, it would be the culmination of a legacy in which the trail of China's coffee beans links the remote village of Zhukula to the globe.