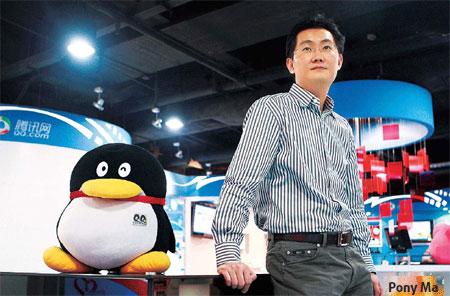

Pony Ma is a mystery to many. He seldom accepts interviews, but his name appears in the media almost daily. He (whose Chinese name is Ma Huateng takes his English nickname from his surname, Ma which means "horse" in Chinese) is rarely involved in any public debates, yet due to his success some in China's Internet industry regard him as a "public enemy".

As the founder and CEO of Tencent, China's largest instant messaging company, Ma always smiles, but more like a shy fresh graduate, rather than a sophisticated and charismatic leader. That presents a sharp contrast to his aggressive counterparts such as Charles Zhang from Sohu.com Inc or Jack Ma from Alibaba Group who aren't shy about reminding people of their unique existence.

Tencent has not only survived but also grandly prospered during the past ten years. By the third quarter of last year, active user numbers of QQ, Tencent's flagship instant messaging software, reached 350 million, 50 million more than the entire population in the United States.

Its business ranges from instant messaging, e-commerce, portal websites and games, to products such as toys and sportswear. They all helping boost Tencent's market value to double that of Baidu Inc, Alibaba, Sohu.com, Sina.com and Shanda Interactive Entertainment combined.

However, Ma, 38, contends that his success derives from being a copycat. "When we were a small company, we needed to stand on the shoulders of giants to grow up," he said, paraphrasing a quote attributed to Isaac Newton: "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

"But copying others can't make you great. So the key is how to localize a great idea and create domestic innovation," he said in a recent rare press conference for a limited number of media representatives.

Starting from copying

Like many of other Chinese Internet start-ups, Ma's success started with ideas from foreign companies.

In 1998, Ma quit his first employer, Runxun Communications, a telecom service company and established his own company in Shenzhen with his five classmates doing a paging business for domestic telecom operators.

On one occasion Ma saw a presentation for ICQ (homophone for 'I seek you'), the world's first Internet-wide instant messaging service developed by an Israeli company in 1996. (Before that, people could only send digital messages via e-mail).

Although ICQ was very popular in western countries at the time, it had no Chinese edition. Inspired by the idea and the popularity of pagers (China's beeper subscriber base reached 46.74 million by the end of 1999) in China, Ma and his team soon worked out a similar software program in February 1999 with Chinese interface and named it OICQ (Open ICQ).

In fact, Ma initially did not expect that his new software would make him rich. At the time, his goal was to sell the software to telecom operators to adopt it as part of their paging service. But since few companies were willing to pay an adequate price, Ma decided to keep it.

He then made a bold move to post the software on the Internet allowing users to download it for free, which later sparked an explosive user growth. By the end of 1999, nine months after the software was first released, OICQ's registered user number surpassed 1 million, making it one of the largest instant messaging software in China.

Name game problems

At the same time while Ma's business was getting on track, Tencent also started to be scrutinized by other companies.

In March 2000, AOL (American Online), which bought ICQ in 1998 for $407 million, filed a lawsuit with the National Arbitration Forum in the United States accusing OICQ's domain names OICQ.com and OICQ.net of violating ICQ's intellectual property rights.

Because of the similarity between OICQ and ICQ, Tencent quickly lost the case and had to shut down OICQ's websites. In the next two years, Tencent.com became the main entrance for OICQ's users.

After the case, Ma started thinking of changing product names to avoid further lawsuits.

In December 2000, Tencent released its latest version of OICQ and the software name was formally changed to QQ (nickname for OICQ). At the same time, Ma voluntarily omitted most of OICQ's previous avatar images that were directly ripped from famous Disney cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck.

Although these measures raised little discomfort among its users, they worked well to help Tencent avoid further lawsuits and paved the way for the company's future success.

Becoming profitable

Although QQ successfully gained a great number of users by 1999, technically it could hardly be called a business as Ma hadn't been able to find a way to cash in with its huge user base. At that time Tencent had some other business from local telecom carriers, but its revenue could not afford the surging cost in servers and bandwidth brought about by the flood of QQ users.

"We knew our product had a future, but at that time we just couldn't afford it," Ma remembered. In order to solve the problem, Ma asked for bank loans and even talked to others about selling the company.

After a few futile tries, Ma started to look for investments from venture capitalists. In 2000, the US investment firm IDC and Hong Kong telecom carrier Pacific Century CyberWorks (PCCW) decided to invest $2.2 million for 40 percent stake. That gave Tencent the ability to support more users and, more importantly, provided Ma the necessary time to find out a way to generate revenue from millions of QQ users.

Soon, Ma kicked off his first try.

By 2000, beeper users declined significantly and mobile phone started to become popular in China. Feeling the potential of this new market, Ma quickly worked out a service that enabled QQ users to send messages directly to other people's handsets. He then successfully convinced local telecom operators to share revenue through message fees. In Tencent's early days, this service contributed over 80 percent to the company's total revenue.

Tasting his first success, Ma quickly rolled out other value-added services such as virtual images and games and tried to promote online advertisements on QQ software. He also built up Tencent's own payment system: QQ coin, resolving its reliance on telecom carriers to generate revenue.

By 2001, Tencent started to make a profit and its registered users surpassed 500 million.

Changing tactics

Although he gained huge users, Ma soon came across a new crisis. By 2002, QQ became very popular among Chinese people, especially students. A QQ account, which consists of digital numbers and randomly allocated by Tencent to its users, became a status symbol.

In some places, special QQ account numbers, such as 88888 or 66666 (6 and 8 are lucky numbers in China) were sold, or stolen and then sold, at a high price in the black-market. Some users even registered tens of QQ accounts in one day in order to get their favorite account numbers. In 2002, register users increased almost 1 million every day.

Feeling the pressure in surging costs, Ma decided to charge fees for the account registering service.

In 2002, Tencent gradually reduced the capability of its free account registration service and made it possible for users to register accounts through telephones and short text messages.

Unexpectedly, this move quickly angered most QQ users, who regarded it as a fundamental change of QQ's long-held free policy. Many argue that because Tencent already had revenue from ads on QQ, it should not charge for just registering an account.

As a result, many of QQ users started to leave and turn to newly emerged instant messaging software such as Langma UC (acquired by Sina in 2004 for $36 million) and POPO from NetEast. Other players such as Microsoft's MSN messenger, Yahoo! messenger and ICQ also started expanding in China.

In response, Ma had to resume QQ's free registration and continued charging for avatars, virtual gifts and other online services.

Diversification

After that, Ma started to diversify its business. In 2003, Tencent released its own portal website QQ.com and entered the online game market. In the following year, Tencent was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, helping Ma to become one of the richest people in China's IT industry.

In 2005, the company launched its C2C platform Paipai.com and putting itself in direct competition with e-commerce giant Alibaba.

"China's Internet users will continue to grow at a significant speed in the next three years but there will be fewer spaces for new players when user numbers reach 500 million," said Ma. "So it's stupid not to invest now."