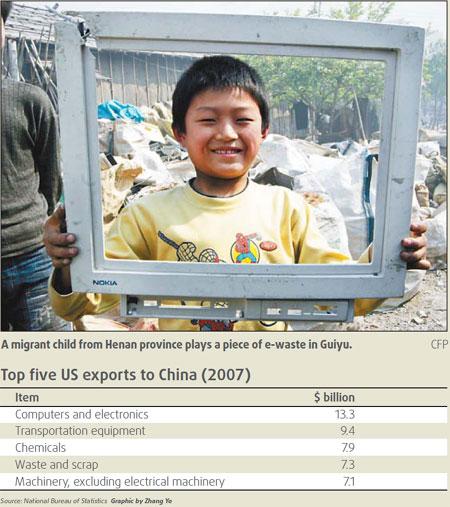

Officials in Guiyu of Guangdong province were baffled last fall when "60 Minutes" reported that the village of Guiyu was drowning in toxic e-waste.

"This is an entire village of electronic components," marveled CBS correspondent Scott Pelley. "It's the most amazing thing!"

The report was amazing to local officials because many of the practices it exposed had been outlawed since 2005.

Also, it wasn't Guiyu.

"Guiyu has been dealing with the pollution problem since 2000. These efforts were re-doubled in 2005, when Guiyu was named a 'pilot town' for recycling by the National Development and Reform Commission," Lian Wuming, head of the Guiyu township government, told China Business Weekly last week. "These effort have paid off," he said.

Since 2006, Guiyu has spent more than 100 million yuan to improve recycling practices and treat pollution, according to Lian. The burning of plastic and other waste cited in the CBS report has essentially been stopped, he said. "Key pollutants are now under control, and practices such as randomly burning wastes and extracting precious metals via melting or acid baths have basically been stopped."

Recyclers in Guiyu deny that their town is a dumping ground for foreign countries, as reported on CBS. And according to Zheng Junmian, director of Guiyu's general office, the report wasn't even filmed there. The village that amazed Pelley was actually nearby Puning.

No one denies that Guiyu, Puning, and many other villages involved in the recycling business are polluted. "The current pollution problem is caused by the treatment of e-waste in primitive household workshops, dating back to the 1980s," Lian said.

He conceded that some such workshops "are still illegally extracting precious metals in a very simple and backward way," but said that last year alone, the town shut down 80 workshops and prosecuted 400 cases of illegal burning.

Most of the e-waste in Guiyu and neighboring towns comes from Guangdong and Zhejiang, according to local recyclers.

"I don't think any of the e-waste here comes from overseas. Chinese customs is on the lookout for e-waste and they keep it out," said Chen Yinghong, the owner of a recycling shop in the coastal city of Shantou.

"And the e-waste we're recycling is nowhere near as toxic and polluting as some of the media report. You can see with your own eyes what's going on," Chen said.

Chen's shop has ten employees, each of whom makes about 1000 yuan per month. They pick the computer components apart by hand, using small hand tools. This method is more labor-intensive and therefore more expensive than earlier methods, Chen said, but it is also safer.

None of Chen's family or employees has had health problems related to recycling, he said. A local doctor, who identified himself as "Lin", added that few if any of his patients seem to have suffered from pollution.

Business is slow right now for Chen and recyclers throughout China.

"Metal prices have nose-dived by at least 60 percent in the past half-year due to the global financial crisis," Chen said.

"We've actually been running at a loss for the past few months," he added. "I don't intend to sell any more recycled metals until the price goes up."

About 40 percent of the shops involved in recycling e-waste in Guiyu have either cut back or shut down, according to Lian. Still, recycling accounts for 90 percent of Guiyu's revenue.

While business is slow, Guiyu is continuing to upgrade its recycling industry. The town has already set up 10 new recycling centers, each capable of processing material worth 10 million yuan a year without significant pollution.

With a budget of 2.2 billion yuan, Guiyu hopes to establish itself as a recycling hub, incorporating 3000 household workshops with a capacity of 1.4 million tons of e-waste annually.

In the meantime, however, the global slowdown has hit China's recyclers hard. Much of the e-waste processed in Guangdong used to come from other parts of the country, where computers and other appliances were ripped down and shipped south for processing.

That trade has all but stopped. In villages like Houbajia, outside Beijing, recyclers sit idly in their shops, waiting for metal prices to recover.

"I'm broke," said scrap collector Zhou Gang last week, puffing a cigarette while slowly dismantling a broken computer.

Zhou borrowed $10,000 from his family to get into the recycling business. Now, all he has to show for that is a mountain of e-waste that is hardly worth recycling.

"Back in 2003, guys used to make $100,000 a year doing this. Now, we can't afford $70 a month to rent a house," lamented Gao Xing, who shares a yard with Zhou and 10 other households.

"The economic crisis hit us all of a sudden," he said.

Scrap dealers typically collect e-waste by bicycle and process it as inexpensively as possible. Environmentally friendly methods are more expensive, but once they are mandated, experts believe the prospects for recycling in China are bright.

"Regulation will put safe recycling operations on a sound financial footing," said Wang Yong, an executive with the Huaxing Environment Protection Development Co Ltd in Beijing.

"Once that happens, the potential rewards for recycling enterprises are enormous," he said.