Farmers try to beat drought but traditional ways endangered by more than just weather, Cao Li and Zhao Ruixue report in Shandong.

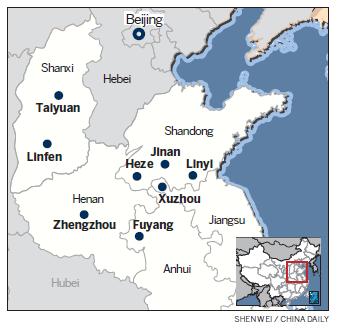

Snow falls quietly on parched wheat fields as electric generators roar to bring water from far away. Li Guangxue waits anxiously for water to arrive on his 3-mu (0.2-hectare) plot in the high-altitude fields of Wucun township in Shandong province.

"The wheat crops have had no water since they were sown. The damage is already done and the snow came too late and was too light," says Li, a 49-year-old farmer whose bronzed face bears testimony to a lifetime working the land of hilly Qufu, where he lives.He picks up a wheat plant with a shriveled root. "This is the worst drought I have ever seen."

There's more at risk than withering plants and a harvest that helps feed millions. A way of life is withering, too, as the costs of farming increase and the natural resources critical to farming are diverted to other uses.

Even after watering with the imported water, Li predicts a decline of 150 kilograms per mu in the harvest, which in a good year yields 500 kg. He expects to make about one-third of his usual profit, counting the investment in watering equipments.

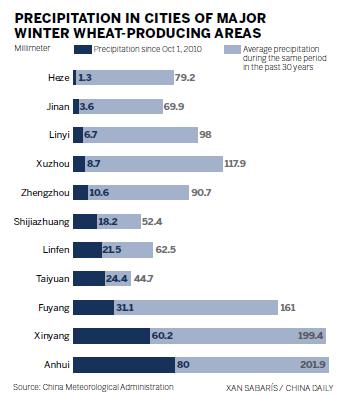

Li is just one of millions of farmers in northern China who are seeing their wheat plants wither in the most severe drought to hit the region in six decades. And no effective precipitation is forecast for the near future.

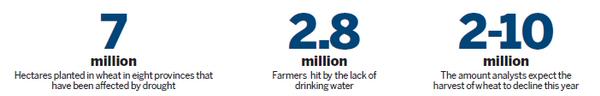

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, more than half of the 14 million hectares of wheat fields in eight provinces, from Shandong to Gansu, have been affected. Henan, Anhui and Hebei provinces have been hit badly. More than 2.8 million farmers and 2.5 million livestock feel the lack of drinking water.

Analysts expect the wheat harvest to decline by 2 million to 10 million tons this year; the 2010 harvest totaled 113 million tons. The drought is ramping up the price of wheat, which is having an impact both domestically and abroad, according to a report from the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization. The national average retail price of wheat flour in China was 4.42 yuan (66 cents) a kilogram in August and 4.8 yuan on Feb 4, a rise of 8.6 percent.

|

A farmer watches as water trickles into the furrows of his wheat field. This water came from a nearby reservoir, at Beichen village in suburban Jining, Shandong province. [Photo/China Daily] |

Can't wait for nature

Every village is mobilized to save the wheat. Li's town, which has relied on farming for generations, is just one of them. "I started farming when I was in the womb," he said.

Qufu is experiencing its worst drought in 200 years. And Wucun town has no nearby reservoirs, natural lakes or abundant underground water.

Qiao Guijun, the governor of Wucun, was busy on Sunday instructing workers to set up more electric generators and pipes. "We are piping water from three water resources 3 to 5 kilometers away and digging tunnels to divert more. We can't wait for the mercy of nature any more." The township government has spent more than 1 million yuan ($151,000) since November.

Nearly half of the town's 45.5-hectare wheat fields had been watered by Sunday.

Li Guangxue purchased plastic pipes to divert water to his land and diesel fuel to power generators. "The plastic pipe is much more expensive than last year," he said. He has spent about 800 yuan fighting the drought this season.

In a neighboring field, 60-year-old Kong Fanyou operated a newly purchased electric generator. He paid 1,000 yuan for it. "If I don't water the plants now, there will be no harvest at all."

For some farmers, equipment to combat the drought is costing more than their annual income. But there is help. In Yuncheng county, in Heze city, electrical engineer Diao Zhaochang stood at the entrance of Hehai village, waiting for calls to power the water piping. "We will generate electricity for whoever needs to water their wheat fields," Diao said.

Although Heze, the region's major wheat producer, sits on the northern bank of the Yellow River, it is limited in its use of the resource. The riverbed in some places has dropped, and limits on withdrawals have been imposed. Locals said that villagers dig wells every day to find new water sources for the thirsty crops.

Many officials say the drought will not have a lasting impact on production because more wheat has been planted for this year. But drought could be an ongoing problem.

| The roots on this wheat plant, held by farmer Li Guangxue, look like dried and dirty string. That's the work of the severe drought in northern China. [Photo/China Daily] |

Other threats

Scientists say China's rapid industrial development, economic growth and changing habits are having a serious impact on its environment and globally. But drought is historically common in China's north, and cyclical; 2009 was particularly harsh.

Zhu Guilin, vice-director of Jining Meteorological Bureau, said cold fronts from the north control the region, leaving no space for warm air or a mix of warm and cold that would produce precipitation. He concedes that there have been dramatic weather changes in recent years but said, "It is hard to say whether it has anything to do with climate change."

Water shortages in the north of China have long been a concern, prompting the government to introduce a project to divert water from southern China to the north. But industrialization and urbanization mean that water consumption is on the rise.

Environment experts report that per capita water consumption in urban households can be up to three times that in rural households. That doesn't include water consumed in luxury activities such as golf, which is gaining popularity in cities as people become wealthier.

In the bustling city center of Jining, an hour's drive from Wucun, city dwellers are virtually unaffected by water shortages less than 100 km away. It is business as usual for carwashes. Guests in restaurants are automatically served water; they don't have to ask for it, a practice sometimes used in drought-stricken regions in the United States.

Li Minghui, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences' institute of agricultural economics and development, said industrialization represents as serious a threat to the Chinese wheat industry as drought. Factories occupy farmland and their pollution threatens the environment and, as a result, farming.

"Digging wells and diverting water from rivers could relieve drought in the short term," he said, but they pose potential long-term risks. Officials admit they are digging wells deeper and deeper. In Gaoyi village in Hebei province, a crack in farmland that is 50 meters long and 1 meter deep is blamed on draining underground water.

But Li also said technology may help farmers address such problems even as city dwellers use more water. Industrialization facilitates farming with better technology and equipment, he said, allowing more farmers to leave villages to find city jobs without diminishing crop production.

He predicted that farmland will consolidate, which will make dealing with issues like drought more effective. "In the future, it will be big companies or the best farmers who take care of the farming."

|

Farmers pump water from a well to irrigate their wheat crops in Yuncheng county, Shandong province, last week. [Photo/China Daily]

|

Changing landscape

Yuncheng county, which was once a purely farming community, now boasts a successful textile industry. The population is aging. Young men drawn by economic growth leave for big cities to work and women work for textile factories, leaving the fields behind. Officials say it is hard to estimate the impact of those changes on farming now.

He Bangxiang, 40, stood in his field on Friday after watering his 3-mu wheat plot, but he will leave for Shanghai soon to build roads. He brings home about 10,000 yuan a year from that work, while the total wheat harvest, even in good years, gets his family about 1,500 yuan.

His neighbor He Jiancai, 43, is going to Beijing to work at construction site.

Zhai Deling, a resident of rural Wucun, is not worried about the drought. She once farmed wheat, but changed to berries, which are more profitable and need less water and care. She is restricted to just four hours of tap water a day in the morning, but saves the water each day in a large tank in her yard.

Her real investment is not with land, she said, but in her 19-year-old son. He attends university in Yantai, a developed coastal city. He is studying to become a technician and has no intention of returning to the family's 3-mu plot.

"It is up to him to decide his future," Zhai said. "I don't want him to go back to farming."