Brazilian model Gisele Bundchen watches the first night of the Carnival parade in Rio de Janeiro's Sambadrome February 22, 2009.

On a street in Rio's Ipanema beach neighborhood, Juju Maravilha, dressed in a sultry gold and green sequined gown topped off by a headdress of yellow feathers, takes less than five seconds to ponder a question.

"The soul of Carnival? Why it is here, darling," he coos, pointing at a crowd of thousands gathered for one of Rio de Janeiro's more than 200 informal street marches that give life to the yearly bacchanal of music, flesh, dance and drink.

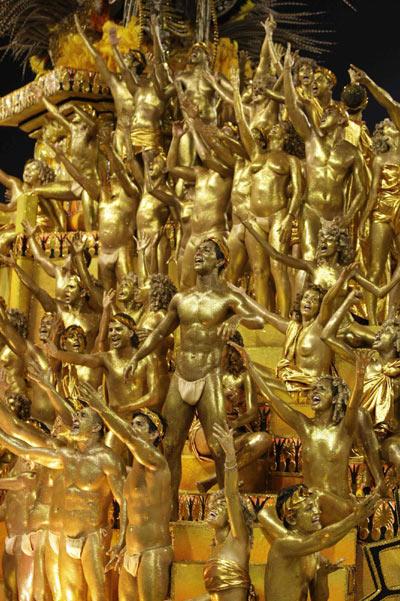

The showcase event of Rio's Carnival is undoubtedly the two-night parades put on by traditional samba schools — ornate spectacles costing up to $2.5 million each with thousands of drummers, dancers and meticulously designed floats that begin Sunday night.

But locals and tourists in the know say the true golden center of Carnival lies in the parties — known as "bandas," which play the same traditional songs each year, and "blocos," which mix up the music each time. With tickets to the samba school parade running upward of $1,000, these free parties keep Brazil's No. 1 tourist attraction accessible to all.

"The origins of Carnival are in the streets," said Paulo Montenegro, a 48-year-old lawyer taking part in Friday's "Hit On Me, I'm Willing" bloco. "That is why blocos are so important — it is free, democratic, and passes on the traditions of Carnival."

The parties occur each weekend for three weeks leading up to Carnival, but began rolling nonstop Friday afternoon. As the last revelers dragged themselves home at sunrise Saturday, some 500,000 people crowded into Rio's center to celebrate the 90th year of the Black Ball Krewe — one of the most traditional and beloved.

In the Banda de Ipanema samba troupe's first march, about 30,000 people shuffled behind musicians and cross-dressing dancers done up as Carmen Miranda, the Brazilian singer who helped export samba to the world in the 1940s.

"It's a great cultural manifestation. You see children, older women, men, girls, gays, straights — it's a beautiful democracy of the streets," said Juju Maravilha, or "Marvelous Juju," before turning on his heels and posing for a photo with a family.

Rio's blocos are a tradition going back about 100 years and exist in nearly every part of the city of 6 million. Unlike luxurious Carnival parties attended by the elite and hosted in posh hotels, they're open to anyone who shows up with a smile and feet ready to dance.

"It's the most beautiful part of Carnival, and here you will see all the tribes," said Joao Jadiole, a 35-year-old mechanical engineer from Rio, as he danced behind the Banda de Ipanema, shirtless, a can of beer in each hand. "The banda is peace, love, life, liveliness — everything that is wonderful about this city."

There is little method to the madness, but the blocos begin with a "concentration": a vaguely adhered-to appointment for gathering at a plaza, a street corner, wherever.

Banda de Ipanema met on a recent Saturday at 4 p.m. in one of the neighborhood's main plazas. This being Brazil, where the only event that begins on time is lunch break, by 4:20 only a few tourists and a horde of beer vendors were there.

Around 4:30, band members began showing up, trumpeters started tooting their horns, drummers began pounding out rhythms and hundreds of people — from young families to elderly women covered in silver glitter and dressed in skimpy bikinis — surrounded the musicians.

By 5:00, after playing several traditional Carnival songs to which the crowd lustily sang along, the band began making its way down the street toward Ipanema beach and the party quickly hit a fever pitch that lasted for several hours.

Banda de Ipanema, founded in 1965 under the shadow of Brazil's military dictatorship, prides itself on irreverent political satire.

Daniel Sbruzzi, a 62-year-old who was well into his suds as the party began, said he dressed up as a female "cousin" of President Barack Obama.

"Obama is going to be a revolutionary with no negative sides. Only positive," Sbruzzi said, hiking up his blue hula skirt and righting his long, blond wig. "He is an idol for the world, and I wanted to express how he makes us all feel like we are part of his family."

Irane Carneiro, who declined to give her age but appeared to be in her 60s, wore a red miniskirt, a gold tank top, at least four pounds of beads, a feather headdress and a good inch of makeup. She tried to explain the importance of the event, which she has attended since its inception.

"If a person loves to be happy, to live life, to leave their problems behind and take to the street with thousands of friends where for a moment everything is wonderful, then they will understand the true face of Rio de Janeiro's Carnival," she said.