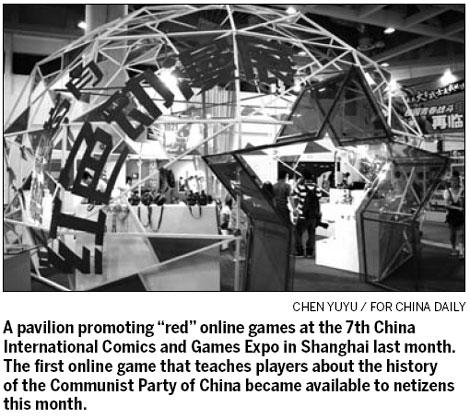

At an Internet cafe in Shanghai the other day, Wu Wencong made a routine appearance online. A hardcore online gamer, this time he selected a character that was out of the ordinary for him. It was not a warrior or a monster but a communist youth.

Wu named his avatar "Xiao Li". The young man's task was to organize villagers to fight a publicity war against enemies. Xiao Li had to fulfill a list of tasks to win the hearts of his fellow workers so that they continue farming and handing out leaflets. In this way he earns more credits.

Named after a well-known Chinese revolutionary book, the game Xinghuo (A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire) aims to indoctrinate players with classical communist theory.

Wu registered his identity on the game's website on Aug 3, the third day after its launch. "It sounds excellent. I have played so many Western games that make little sense in the real world. Another perspective is necessary to keep my sensibilities balanced," Wu told China Daily.

Not everyone predicts a rosy prospect for the "red" game, not even its designer, Ma Xiang, executive director of Shanghai Online Information Technology Co Ltd.

The idea originated with the establishment of the Shanghai Serious Game Industry Development Union, a nonprofit organization that spreads the notion that games can be designed for a purpose other than pure entertainment, Ma said.

"Games can be guides, textbooks, medical facilities - anything you can think of," the proud 31-year-old added. "This year being the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, we think it will be a meaningful initiative to rekindle communist zeal."

Researchers were given free rein over the past three months thanks to support from the Shanghai municipal government. The game offers historical background about the revolutionary base in Northwest China's Shaanxi province, where the late leader Mao Zedong lived for more than a decade during the civil war (1927-1936) and the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945). It also provides biographies of key figures.

Ma and his colleague Wang Qi took a long time to create a plot. As the general manager of a gaming studio, Wang said his team of 22 were undecided about whether they should stick to historical truth or simply reflect the revolutionary spirit.

"We didn't want to make mistakes in the history so we downplayed details and opted for a grand narrative," Wang said. The game does not highlight specific episodes, such as the Long March or Pingjin Campaign, but the revolutionary age in general.

To seasoned players, the game-play may not be particularly sophisticated or exciting. Images of heroes look like 1930s wood prints. Unlike bloody zero-sum games, Xinghuo encourages players to pass on communist theories and to coexist peacefully.

"It doesn't appeal to me at all, and I won't even consider playing it," said Yong Jun, a senior at a Shanghai university. "I am far from a model student at school, and I dislike having those doctrines preached to me during games."

Wang Ying, 55, took a different view. The recent retiree said she would give it a try because it aroused a sense of nostalgia and recaptured the spirit of a bygone age when millions of ordinary Chinese successfully fought in China's communist revolution.

According to statistics compiled by Analysys International, a domestic Internet research firm, older game players have started to become mainstream Internet users.

"Currently, 12.5 percent of online gamers are more than 30 years old. As traditional forms of entertainment including movies and TV series go 'red', there should be a solid user base in this market segment," Yu Yi, an Internet specialist with Analysys, told China Daily.

Zheng Chongxuan, a researcher with Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, doubted the game would achieve its desired goals after its sizzling debut.

"It may seem to be a creative move, but the game may fail to maintain the interest of young players because it is not a communist history quiz," Zheng said. "Rather than an integral part of the game, the historical narrative section has some paragraphs only available to those who complete certain missions, which makes the literature part clich-ridden."

Ma and Wang know these by heart. They didn't bother to set a target audience and don't expect big business from the game. It is "an attempt to foster a bit of comradely backbone in modern China's increasingly materialistic society", said Wang.

They insist they have found an intricate balance between the market and politics. "If Americans can sing their national anthem in rap, why can't we tell the glorious communist history in games? The game is by no means perfect, but it is a trial product through which we are looking to move forward," Ma said.