[By Zhou Tao/Shanghai Daily]

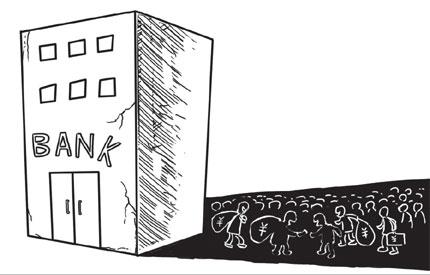

For a long time Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province, a hub of private enterprises, has arguably been a poster child of China's robust private sector. Yet the recent cash flow debacle that unfolded there has seriously called that perspective into doubt.Twenty-nine business owners have fled Wenzhou, leaving behind a huge pile of outstanding debts. As of August, the aggregate number of debt defaults had surged 25.73 percent from the same period last year and the money at stake amounted to over 5 billion yuan (US$733 million).

The desperate situation has prompted the central government to intervene to bail out Wenzhou's struggling small firms.

Given this bleak picture, the booming underground financing in Wenzhou is an anomaly. The Wenzhou branch of People's Bank of China, the country's central bank, found in a recent survey that "shadow banks" in Wenzhou have 110 billion yuan at their disposal, with 89 percent of local families and individuals and nearly 60 percent of firms involved in the credit trade.

The central bank's conclusion is that "underground financing has become the primary investment alternative to real estate." Shadow funding has pulled in huge funds for private equities in some locales. The promise of high return, at a staggering ratio of 10 or even 100 times the original investment, has attracted money-rich investors tired of the sluggish stock and property markets.

Cash-strapped banks have no choice but to release high-risk financial products to win back customers drawn to the lucrative shadow credit business. At a time when credit tightening has considerably cramped the money flow, we can still see some investment projects netting more money than expected.

This is an indication that China doesn't really have a cash flow problem. A lot of idle money has even poured into the commodities market and pushed up prices of agricultural products and industrial raw materials - the last thing state regulator wants to see.

The speculative run has complicated efforts to combat inflation and forced the central bank to roll out measures aimed at draining liquidity. But the contrast between a cash-strapped Wenzhou and a cash-awash Wenzhou has called to mind the limits of credit tightening.

A majority of the medium and small enterprises that suffer a credit crunch today are those impacted by the nation's industrial overhaul in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. They are regarded as redundant and obsolete because of their high operational costs, vast energy consumption, severe pollution and low output.

The increase of fuel and utility prices and the rapid appreciation of the yuan, together with the forced brownouts to meet green goals in some areas, combine to make life more difficult for them. Many expected these small companies, with high maneuverability, to lead the industrial restructuring and upgrading. That's not happening. What we see instead is they are tripped by predicaments of the transition.

Some companies withdrew from the real economy long ago. With industrial capital and cheap bank loans secured through collateral, they have invested in real estate, commodities, art collection, vintage wines, and private equities in anticipation of high yields. But if these investment choices don't work out, credit problems arise. The indebted businesses have to either sell their assets or borrow on usurious terms to service loans. They appear to have chosen the second option to fill funding shortfalls.

1 2 Next