Curled steel plates rust while lying idle in an iron and steel factory in East China's Jiangsu province. China's steel output was 567 million tons in 2009, much more than actual demand for the year in the domestic market. [China Foto Press]

Economists fear manufacturers and developers may be producing goods and infrastructure nobody wants, report Andrew Moody and Lan Lan in Beijing

Once the red ribbon is cut on any new project, it would involve a huge loss of face in China for it not to go ahead.

The ever-looming potential dark side of China's 4 trillion yuan stimulus package is that many schemes under construction could be serving only to create capacity for which there may be no obvious demand.

This does not just involve questionable infrastructure projects such as roads to nowhere, airports to where no one wants to fly or vacant commercial office blocks - now seen in many of China's cities - but also new factories and industrial plant producing goods that nobody wants to buy.

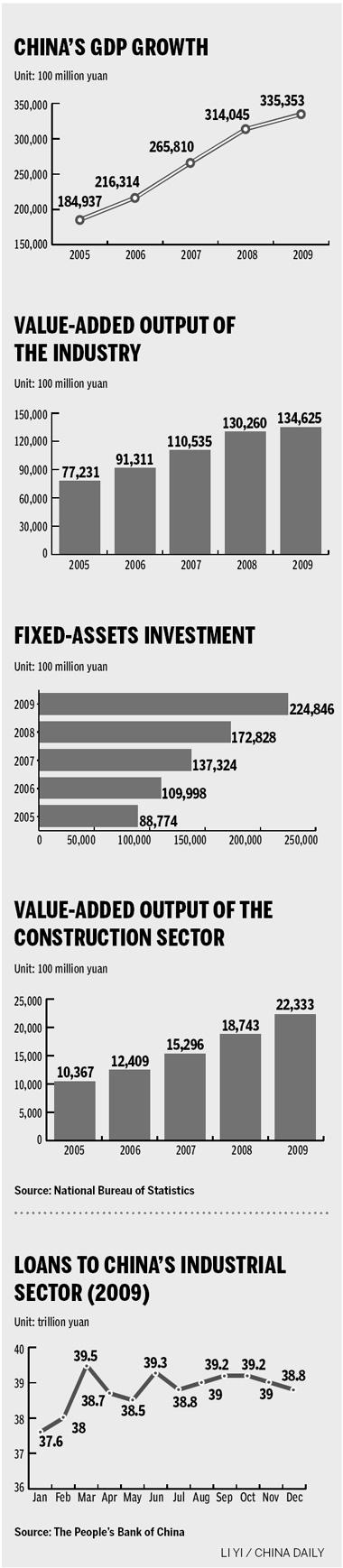

The problem has been building up for some time. China's gross industrial output (mainly heavy industry production) grew at a rate of 1.6 times that of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) in the five years up to 2008, according to a recent report by international strategy consultants Roland Berger and the European Chamber, which represents major European companies.

In other words, the production capacity of the economy was growing at a faster rate than demand in the domestic economy could bear.

Excessive supply

The only possible safety valve was for much of this production to go for export, creating a surge in supply and potentially destabilizing prices.

A big concern recently has been steel production, with China creating 58 million tons of extra capacity in the first half of last year when global demand was expected to decline by 14.9 percent.

China's State Council has been acutely aware of the problem of overcapacity, saying in a recent statement that local governments were often "blindly" making "duplicated investments".

Bernhard Hartmann, partner and managing director of international management consultant A.T. Kearney in China, said that one aspect of the burden of overcapacity was cultural.

"You can imagine the loss of face there would be if the guy had cut the red band and everything had started and then someone said: 'Let's stop'."

He added the problem was exacerbated by the speed with which major schemes can be constructed and a general lack of co-ordination across the country.

"In China major projects can be built in a matter of months, whereas in the West they might take five years to put up," he said.

"If eight cities were building technology parks, all eight would be built before anyone could go back on the decision.

In the West, when you got to park number six and a feasibility study revealed there was no demand for it, it would simply not go ahead."

Charles-Edouard Bouee, president and managing partner of Roland Berger Strategy Consultants in China, said the problem of overcapacity in China had been exacerbated by the deep recession in the West.

"Industrial overcapacity has a strong impact on companies at every stage of the supply chain and on end users. As demand for China's exports has plummeted in the US and Europe and fixed asset investment has risen sharply in some sectors, the problem of overcapacity has been amplified," he said.

The State Council recently highlighted six key industries in which overcapacity was a problem, namely, iron and steel, cement, glass, coal chemical, poly-crystalline silicon (used in the solar energy industry) and wind power equipment.

One sector also struggling with overcapacity is aluminum in which China is now the world's leading producer. China now has 20 million tons of primary aluminum capacity, yet in 2008 only 67.5 percent - 13.5 million tons - was utilized.

Aluminum Corporation of China (Chinalco), the country's largest aluminum producer, recorded a loss of 4.6 billion yuan in 2009 as prices fell, largely due to over-supply on world markets.

The company closed two production lines in Central China's Henan province in January this year.

Lu Youqing, vice-president of the company, said recently the company needed to diversify out of aluminum.

"We must expand into copper and other metals as this is the key to our survival," he said.

"The impact of overcapacity is subtle but far reaching, affecting dozens of industries and damaging economic growth not only in China but worldwide," said Joerg Wuttke, president of the European Chamber.

Peter Markey, a mining analyst at international accountants Ernst & Young based in Shanghai, however, believes there is evidence of the overcapacity in mining and metals sector easing this year.

"Demand has picked up quite a lot but there are still some pockets of overcapacity and it is not like offices, motorways or railway links, " he said.

He said the government has made a number of moves to control capacity in the steel industry, but sometimes they are met with resistance.

"It has been trying to shut down older plants, steel mills that were built 10 to 15 years ago that consume too much electricity, but they are often the only factory in a particular area and there is no guarantee that their replacement is going to be in the same place, so there are a lot of local pressures," he added.

Wu Changqi, professor of strategic management at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University, said one of the results of the stimulus package was to put on hold decisions to cut back on excess capacity.

"With cheap finance being available firms have been able to prolong the phasing out of certain outdated capacity. I think the stimulus package has inevitably put off making necessary restructuring decisions," he said.

Wu added that it was not an easy process for an economy to rid itself of overcapacity, citing the great economist Joseph Schumpeter, who said it often required some big external shock.

"This was evidenced after the World War II when a lot of old capacity was destroyed. Before the war there was very little innovation but after it companies were forced to modernize. It was in this period that you saw the emergence of Japan," he added.

Wu said the flood of money being pumped into the economy had created an artificial situation.

"In normal circumstances, if someone running a firm makes bad decision he will be penalized. He could go bankrupt. His assets would be bought up and allocated elsewhere. This is actually a creative destruction process which isn't happening right now," he said.

There are faults in the system, which lead to overcapacity, said Zhou Dadi, former director-general of the Energy and Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission, the macroeconomic management agency under the State Council and now a leading international expert in energy efficiency.

Some local governments in China just add capacity because they feel they are judged by how much economic growth they are generating, he said.

"Under a regime where general domestic growth and capital increment are regarded as the main indicators of economic growth this will happen," he added.

"Some local governments are just striving to expand their interests by adding production capacity. Overcapacity is therefore inevitable."

Zhou added that if this continues unchecked, Chinese companies would only get involved in price wars in international markets, which would ultimately damage them.

"The real big problem lies in that the expanded capacity will lead to a price war among Chinese companies in overseas markets. As a result, Chinese companies' average profit margin will shrink," he said.

Hou Qingyang contributed to this story.