Youngsters feel the pain as partners vetted to protect interests. Yu Ran reports from Shanghai.

On the outside, Wang Yue looks like a man who has it all: he drives a smart BMW car, he wears sharp Armani suits and he carries designer Gucci bags.

Yet, there is one thing he cannot have - the woman he loves. The 26-year-old was forced by his wealthy Shanghai family to split from his girlfriend of four years "because we're not a good match", or in other words, because she came from a poor background.

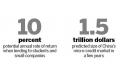

Like in the West, rich Chinese parents have become increasingly involved in their children's love lives, mostly to protect their assets from what sociologists and lawyers say is a "growing culture of materialism".

With the demand for prenuptial agreements rising nationwide, and not just among the rich, many fuerdai - the Chinese term for children born to powerful families - are starting to feel the pressure.

"I don't think I'm lucky enough to meet someone my parents and I both like, so I'd rather stay single," said Wang, who manages a five-star hotel in the metropolis.

"I'm going to concentrate on my work instead. It's the best solution for all of us."

According to the fuerdai who talked to China Daily about their experiences, China's first generation of self-made millionaires are particularly concerned about their children dating people raised in the countryside.

Wang, whose father owns several hotels and holiday resorts and whose mother is a real estate investor, said his parents were "visibly disgusted" when they met his ex, Xiao Mo.

"She is just an ordinary girl from a small town in Sichuan province," he said, his eyes lighting up as explained how they met while studying at Wuhan University in Hubei province. "We saw each other at a party of a mutual friend. It was love at first sight," he said, smiling.

His parents did not share his enthusiasm. "I never expected such an intense reaction," said Wang, recalling the time he took Xiao to meet his parents in the summer of 2007. "When they heard about her background, they were so disappointed. They warned me that the relationship would never work out."

In 2009, after years of fighting, Wang decided to break up with Xiao, who by then had moved back to Sichuan. The final straw had been when his parents threatened to sever financial ties with the couple if they married.

"My parents put too much pressure on us, just because I'm rich," he added.

For money or love?

For money or love?

Faced with the prospect of their child marrying someone "unsuitable", wealthy parents usually resort to one of two options: engineer a breakup or demand a prenuptial agreement.

With inheritances worth billions of yuan at stake, "prenups" are designed to prevent fuerdai from falling prey to gold-diggers.

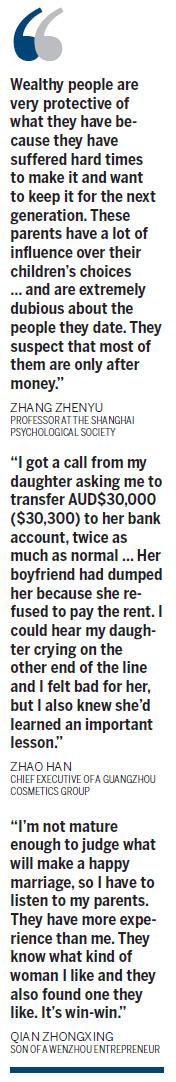

"Wealthy people are very protective of what they have because they have suffered hard times to make it and want to keep it for the next generation," said professor Zhang Zhenyu at the Shanghai Psychological Society. "These parents have a lot of influence over their children's choices and are extremely dubious about the people they date.

"They suspect that most of them are only after money."

In fact, judging by a three-month study to measure the attitudes of almost 1,000 students in South China's Guangdong province, they have good reason to be cautious.

Roughly 60 percent of females polled by researchers with the Women's Federation of Guangzhou admitted they want to marry a fuerdai who stands to inherit a large sum of money from his parents. More than half of male respondents shared the same sentiment.

"Many college students are more than willing to find love with people from rich families as they want to have a comfortable life without working too hard for it," said Liu Shuqian, a professor of ethics at Guangzhou University.

Zhao Han, chief executive of a Guangzhou cosmetics group with more than 500 million yuan ($75.5 million) in assets, said she was fearful when her daughter Deng Tingting went to study in New Zealand in 2004.

"Being far from home, I was really worried that she would be cheated by someone as she has been spoiled and is naive," she said.

The fear eventually became a reality when Deng moved to Sydney, Australia, two years later and started seeing a man from Dalian in Northeast China's Liaoning province.

"I got a call from my daughter asking me to transfer AUD$30,000 ($30,300) a month to her bank account, twice as much as normal," recalled Zhao. "I soon found out she was paying her boyfriend's living expenses."

She refused to increase the allowance and demanded Deng break off the relationship. A week later, she got another call.

"Her boyfriend had dumped her because she refused to pay the rent," said Zhao. "I could hear my daughter crying on the other end of the line and I felt bad for her, but I also knew she'd learned an important lesson."

Now 25, Deng is back in China and working for her mother's business. Like many fuerdai, she has delegated the task of finding a partner to her family.

"I arrange regular blind dates for her with men who meet my requirements of a good family background and fixed assets," said her mother, Zhao. "The only exception is if my daughter finds a man she likes. Even then, he must agree to sign a prenup, as well as give up any job and leisure activities with friends.

"If he's willing to do all these things for my daughter, I'm willing to cover his living expenses for life."

Finding the one

Rich parents like Zhao are increasingly playing matchmaker for their offspring, with varying success.

Although Wang Yue in Shanghai has so far rejected all of the partners "approved" by his family, Qian Zhongxing said his mother has helped him find true love.

After also being forced to split up with a girlfriend from the countryside this year, he is now planning to marry a woman introduced to him by his parents.

"I'm not mature enough to judge what will make a happy marriage," said the 28-year-old, "so I have to listen to my parents. They have more experience than me.

"They know what kind of woman I like and they also found one they like. It's win-win," said Qian, who recently took over his father's trading company and four clothes factories in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province. "I'm lucky to have found the one." The wedding is planned for next August.

Several parents are also enlisting the help of their children's friends to find suitable matches.

Amateur matchmaker Chen Qixia, 46, said she regularly organizes blind dates between wealthy friends in her native Wenzhou. So far, she has successfully forged two fuerdai couples and has become well known among the business community.

"I only offer my assistance to the sons and daughters of good friends, as I have a better idea of what they want," she said. "When we say well-matched, we're talking about similar educational backgrounds and whether their parents have the same amount of fixed assets and property."

However even for well-matched fuerdai couples, Chen insists prenuptial agreements are still vital to prevent conflicts in the event of a divorce.

According to data provided by a Shanghai law firm, almost 90 percent of the divorce disputes it handles between people without prenups are over the division of property.

"Scientifically speaking," said Zhang at the Shanghai Psychological Society, "shared attitudes and values, as well as similar upbringings and education backgrounds, can potentially provide the foundations for a solid married life.

"However, although a parent's desire to find a good match (for their child) is wise, it's not essential," he added.

Names of fuerdai and their parents have been altered on request.