Just three months after his visit to China in November 2003, the Australian architect Peter Davidson was invited by Pan Shiyi, the CEO of Beijing s largest real estate developer, Soho China, to submit a design for the company s newest retail and residential development.

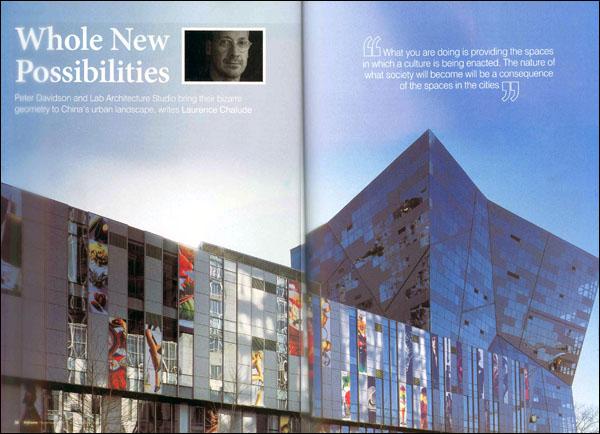

A Whole new part of the world opened its door to me, the soft-spoken architect says of the Soho Shangdu project. Despite a host of strong contenders, Davidson s striking stealth-like design, featuring a black, crystalline facade lined with white neon, won the competition.

Not long after, calls came in from other parts of China. To get the opportunity to experience that was an utter privilege.

It was not the first time opportunity had knocked. Only three and a half years after the formation of his firm, Lab Architecture Studio, Davidson won his first big project: the transformation of Melbourne s Federation Square into a new urban and cultural center.

For any firm, but especially for one that had previously specialized in small interior design projects, it was the opportunity of a lifetime. This was our first building of any scale, a project that was engaged with every level of politics, with the media, and with current debates, which fundamentally changes how you work as an architect, he says.

Everything was at stake. In the small interior jobs I did, none of those things were ever at stake.

The project was a stunning success, creating a set of nine separate cultural and commercial buildings with a combined area of 45,000 square meters, each one with a distinctive, fractal-based design, with the same apparently erratic shapes repeating at different scales.

For Davidson and company, it was the public embrace of the project that gave the firm the confidence it needed to embark on further large-scale urban construction Square to celebrate their national days, he says. For me to have been able to make something where everybody felt like there was something for them was one of the huge rewards.

For the Soho Shangdu project, located on the edge of the CBD, the main task was to make sure the building related to, and engaged with, the street life around it, rather than radically altering the area. Meeting with inhabitants from one of the housing blocks on Dongdaqiao Lu at the beginning of construction illustrated for Davidson the ongoing tensions between brazenly modern architecture and old Beijing.

Everybody in those apartment blocks on Dongdaqiao was really concerned with some of the developments, and whether they were going to be forced to move when they didn t want to. He was rewarded at the grand opening, when those same residents approached him to say that, despite its bold, futuristic style, the building did not overpower its neighbors.

One concern Davidson has is that Beijing is striving towards the modern perhaps a little too fast. In many respects I think they want to renew too much. He compares the current Chinese developments to European movements from an earlier period. We made exactly the same mistakes, Davidson says with regard to the redevelopment of cities, such as those that created slums in London between and after the world wars.

We were trying to eradicate the past to create this new mission and China is kind of reenacting those same movements, rather than learning from our experiences. Renovating and refurnishing, embracing contrasts and diversity, rather than demolishing the old, would be his preference.

I just don t think everything has to go.

But for an architect pushing the boundaries of geometrical design, China s openness to modern architecture is also irresistible. The possibilities in China are helping us understand whole new possibilities for what we can do as architects, not just in China, but also in other places where we work.

He explains this creativity-evident, for example, in Herzog and De Meuron s Olympic stadium and OMA s CCTV building-as the result of a strange mixture of naivety and inexperience, he says. They re kind of open to new ideas, and haven t yet got a series of norms set in place that close down possibilities.

There s also the issue of low labor costs. Davidson says this means there are certain construction projects that are only possible in China; but low-cost labor raises concerns as well. The vast majority of what is being built is not of great quality, he says.

Unfortunately, however, building more slowly is not going to be an option.

While Davidson looks to continue his work in China-projects are ongoing in Yantai and Nanjing-his firm maintains a global view, with offices in Melbourne, Dubai and Landon. With his partner Donald Bates, Davidson currently employs a staff of around 50 people. Despite this involvement in urbanization and the building of high-priced skyscrapers, Davidson remains determined to work across a whole range of scales, from the design of furniture to city planning.

Almost as a matter of principle we don t specialize-so that every time you come to something you actually have to investigate and rethink it through.

Related News

Photos

More>>trade

market

- SOHO China - Pan Shiyi: Superb location and design are critical attributes

- South China Morning Post - Soho China chief feels secure in the spotlight Pan

- CNN - Zhang Xin: Building Beijing

- The Wall Street Journal Asia - Property Firm sets sights on Beijing and Shanghai

- South China Morning Post - SOHO China to expand after winter sleep