A garment factory in Baigou, Hebei province. China's small enterprises are facing increasing pressure from rising costs and some are closing their doors as a result. [Photo / China Daily]

Rising prices have not only been hitting consumers, but also small businesses, Chen Jia reports from the towns of Baigou and Rongcheng in Hebei province.

A decline in freight orders, which started in mid-May, has caused a number of problems for Zhang Yan, the owner of a delivery company .

Zhang owns 30 vans that mainly transport goods manufactured in Baigou town, Hebei province, a major production center for the luggage industry, 102 kilometers south of Beijing. The decline in orders convinced Zhang that a downturn in business was inevitable as bag makers were facing a contraction.

"Two of my clients shut down their businesses last month and some of the others have reduced production because of squeezed profit margins," said Zhang.

Baigou is famous in North China for producing leather bags and suitcases. The town, with a population of about 120,000, has more than 3,000 factories and workshops that churn out 65 million bags annually.

The rapid rise in labor costs and the soaring price of raw materials, together with the increasing cost of borrowing, has left small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) there facing a dilemma.

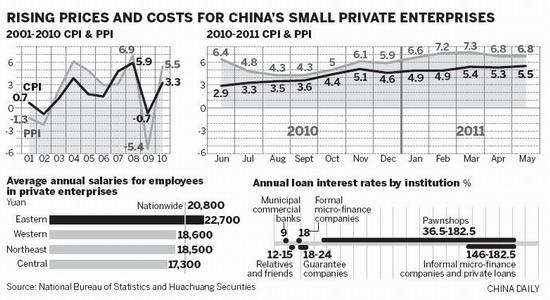

In June, inflation in China showed no signs of abating. The consumer price index, the main gauge of inflation, rose to 5.5 percent in May, and when the figures for June are released in the middle of next month, they're expected to confirm another increase.

Moreover, the Producer Price Index, which reflects changes in the prices of raw materials and other costs, came in at 6.8 percent in May, down from 7.3 percent in March, but still much higher than in September, when it was 4.3 percent.

Meanwhile, the authorities have cracked down on lending and the money supply to combat inflation, a move that has further increased the pressure on China's capital-thirsty small businesses. To make ends meet, some businesses have even been forced to use underground financing sources, which charge exorbitant interest rates. Moreover, wages have been rising continually in recent years, adding to corporate costs.

Along the main street of Baigou where many small workshops are situated, a number of the factory gates have been closed for some time.

"The price of leather increased about 20 percent and salaries have jumped by about 30 percent from the beginning of this year, but we didn't raise retail prices," Liu Hui, the owner of a local bag workshop, told China Daily. More local factories have begun using cheaper artificial leather as a raw material, said Liu.

Liu said: "I cannot say that production will drop this year, but profit will surely decrease. I hope the hard times won't last long."

The rising price of raw materials and limited access to regular bank loans have also encroached upon the only competitive edge possessed by these small-scale enterprises - low costs and retail prices.

Baigou is not the only place under threat. SMEs in Rongcheng, a county in Hebei province where 70 percent of the local GDP comes from the garment industry, are also facing similar difficulties.

Zhou Yancheng, the 43-year-old general manager at Aosen Clothing Ltd Co, has been running his business in the county for more than 10 years. The company's products are mainly exported to markets in Europe and South America.

"As far as I know, many of our previous clients have turned to Southeast Asia, where garment factories can offer lower prices," said Zhou, adding that orders from overseas decreased by about 30 percent in the first five months of this year.

"Now it is the most difficult time for me. It is very hard to borrow money from banks, while overseas orders were even lower than during the global financial crisis in 2008," Zhou said, with a sigh.

In one of his factories, 12 noisy assembly lines were running. "Since the beginning of this year, I have raised average annual salaries by 25 percent, from 24,000 yuan ($3,707) to 30,000 yuan," said Zhou. "It has become more difficult to hire people recently, and the cheap labor that once existed is no longer there."

Gu Shengzu, an economist and senior national legislator, said that companies hiring rural migrant workers have raised salaries by at least 20 percent nationwide since the beginning of the year.

Monetary tightening

When the country's consumer price index (CPI) surged to 5.4 percent in March - the first time that it has risen above 5 percent in almost three years - the authorities emphasized that fighting inflation is the government's top priority.

In order to soak up excess liquidity, the government has opted to reduce the availability of loans, as many think the over-abundance of money in the market has been instrumental in causing rising inflation.

Earlier this month, the People's Bank of China, the central bank, raised the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for commercial banks for the sixth time this year.

The increase came just five hours after the National Bureau of Statistics released data which showed that CPI rose to 5.5 percent in May, a 34-month high. At 21.5 percent, China's RRR is the highest in the world.

The authorities have been tightening the money supply for 10 months, and the country's more than 40 million small-scale enterprises, mostly private, have been feeling the pinch. Making meager profits, many of them have seen their cash flow drying up. In some cases, they have sought out underground lenders, who charge high interest rates.

"Now it is definitely winter for small and medium-sized companies," said Zhang Lijun of the Beijing branch of China Everbright Bank. "Because of the tight controls on credit, banks preferentially choose to lend money to big, State-owned enterprises," he said.

Small and medium-sized enterprises in Wenzhou, in East China's Zhejiang province, were among the first to suffer from the restrictions on lending.

Statistics from the Wenzhou Economic and Trade Commission show that between January and March the city's commercial banks made new loans worth a total of 23.82 billion yuan, 33.5 percent lower than in the same period in 2010. Of the local companies surveyed, 42.9 percent said they have faced a shortage of funds since the central bank further tightened the money supply last year.

The head of a lighter factory in Wenzhou - one of the city's main industries - who only gave his surname as Zhao, said he is considering closing his factory. "With the soaring prices of chemical raw materials, our net profit rate has decreased to 1 percent this year from 3 percent previously," he said.

"Many of the lighter manufacturers I know have closed their factories and opened guarantee companies, which involves lending at very high rates of interest," said Zhao. Guarantee companies make their profits by providing guarantees for borrowers, although in practice some of them also engage in lending between themselves, using funds garnered from banks.

Zhao is not alone in shifting from traditional manufacturing to investing in other areas. Media have reported that the number of companies registered with the local lighter industry association decreased to around 100 in 2011 from the peak of 3,000 some five years ago. And of those 100, more than half have cut production or simply ceased trading.

Yao Chuntao, a member of an entrepreneurs' association affiliated to the Shanghai Federation of Industry and Commerce, said that five of its 20 members have recently closed their factories and started running guarantee companies. He grudgingly admitted that most of these companies are actually engaged in unregulated money lending.

"The annual interest rate for this type of private lending can be as high as 50 percent, and for some short-term loans, it can even reach 80 percent," said Yao.

Most of the guarantee companies have borrowed money long term from other companies or banks and are lending the funds on a short-term basis, a method known as using "bridging loans", Yao said. "The leverage is very risky. If one borrower cannot pay back the money, the whole lending chain may rupture very quickly."

Economic shock

Because SMEs provide about 60 percent of the nation's industrial output and more than 70 percent of urban employment in China, economists are concerned that their predicament could cause a shock to the world's second-largest economy. The survey from the Wenzhou Economic and Trade Commission showed that in the first quarter of this year, one-fourth of the 35 respondent companies in 15 industries said they have suffered losses. Their combined profits in the first quarter decreased by 30 percent to an average 3.1 percent from the same period a year earlier.

In May, the main indicator of manufacturing activity, the Purchasing Managers' Index, decreased to a nine-month low of 52, sparking concerns that the Chinese economy may face the risk of a slowdown. A figure above 50 suggests expansion, whilst one below suggests contraction.

Zhou Dewen, the head of the Wenzhou Association of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, said that if the government doesn't ease its policy of monetary tightening, 40 percent of the city's small-scale enterprises may stop production or even go bankrupt as early as the second half of this year.

China must take prompt measures, such as tax cuts, to provide support for small companies, Gu Shengzu said. "(Tax cuts) would be a smarter method of maintaining social stability rather than simply easing monetary policy."

Earlier this month, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) announced a series of measures to allow greater access to bank loans for SMEs.

Geoffrey Choi, leader of the banking and capital markets department at Ernst & Young in China, said the CBRC's measures are likely to reduce the financial pressure on small businesses.

"The key is that the favorable policies need to continue for some time. Commercial banks are also required to improve their financial services to these private companies," he said.