Birds are the most diverse clade on the planet, and the skull of the living bird is one of the most highly modified and morphologically variable regions of their skeleton. The large diversity of enantiornithine birds (a group closely related to the lineage that includes living birds) uncovered from Cretaceous age deposits around the world is considered the first major avian radiation. During the complex early evolutionary history of the modern bird, it appears many derived features of living birds evolved in parallel in other more primitive groups, and some areas of the skeleton evolved modifications before others, such as the wing and other skeletal elements important to flight. However, few comprehensive studies have been done to test this. Although many enantiornithine species are recognized, and most from the famous Jehol deposits of northeastern China, our specific knowledge of morphological variation, biology and ecology is still incomplete because the rate of fossil discoveries in China continues to be very high. Outside China, only three enantiornithine specimens preserve skull material, however the skull is commonly preserved in numerous Jehol specimens. Because in birds the skull includes the sole feeding apparatus (the beak or rostrum), understanding the enantiornithine skull can help reveal the biology of these extinct birds. However, no attempt to reconstruct and better understand the enantiornithine skull has been made in over a decade.

Together with Dr. Luis Chiappe from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, post-doctoral research of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jingmai O Connor conducted a study on all enantiornithine specimens that preserve skulls in order to summarize the morphological variation known for the clade. This comprehensive study revealed that, like modern birds and closely related non-avian dinosaurs, enantiornithines evolved a number of specializations for different life styles (mud-probing, fishing, etc); however, this study reveals that despite their species diversity, known taxa only occupy a very small portion of the morphospace filled by living birds. Modern birds have very specialized skulls, classified into three groups referring to taxa with very short beaks (brevirostrine), very long beaks (longirostrine), and those in between (mesorostrine); all enantiornithines fall into the mesorostrine category, which is inferred to be the primitive condition for all birds. Although one group of enantiornithines has elongated rostra compared to the others, the proportions do not approach the extreme elongation seen in some living birds (i.e. pelicans). Their work was published in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology 9(1:135-147).

Comparisons were made with the skull of Early Cretaceous basal ornithurine birds; this group includes living birds and is also the sister-group to enantiornithines. Based on these comparisons, O Connor and Chiappe are able to infer what the skull of the common ancestor of these two groups looked like. It was toothed, the premaxilla (bone that forms the tip of the upper jaw in birds) was small, as it is in non-avian dinosaurs (large in living birds) and the cranium retained a post-orbital bone (which is absent in living birds but very big in closely related dinosaurs); the mandibular bones (lower jaw) were unfused and the dentary lacked the forked articulation present in living birds. Overall, the ornithothoracine (enantiornithines + ornithurines) skull, compared to the flight apparatus, which has many advances over more primitive birds (e.g. keeled breast bone, shoulder bones unfused, hand reduced), remained largely unmodified and reminiscent of Archaeopteryx and closely related non-avian dinosaurs (e.g. Microraptor, Meilong). However, the skulls of a few enantiornithine specimens do possess modifications present in modern birds; these specializations (e.g. caudally forked articulation of the dentary and a fully fused mandible, a beak, and an enlarged premaxilla) were evolved convergently (in parallel) in the two major lineages of birds (enantiornithines + ornithurines), and some were also evolved independently by non-avian dinosaurs as well (e.g. the beak in derived oviraptors). This is one of the reasons is it is very difficult to understand bird origins and relationships.

One of the most interesting aspects of the enantiornithine skull is their teeth. Despite tooth reduction in more basal birds (e.g. Sapeornis, Confuciusornis and Jeholornis), enantiornithines preserve a wide range of tooth morphologies. In the Mesozoic, it appears only the enantiornithines (among birds) were actively using teeth to feed. Early Cretaceous members of the lineage that includes modern birds (ornithurines) are either toothless or have only very small teeth; however, they often preserve stomach contents and thus scientists can infer their diet. Unfortunately, stomach contents are not preserved for any Jehol enantiornithine specimen and tooth morphology is the only way to infer diet. The huge diversity of known morphologies and distributions in the jaw (ranging from numerous low-crowned peg-like teeth all along the jaw, to only a few recurved, laterally compressed teeth located at the tip of the mouth) indicates active selection for different uses, and hints at a wide range of dietary preferences including fish-eating, insect eating, mud-probing for soft arthropods, and a diet of hard items (durophagy).

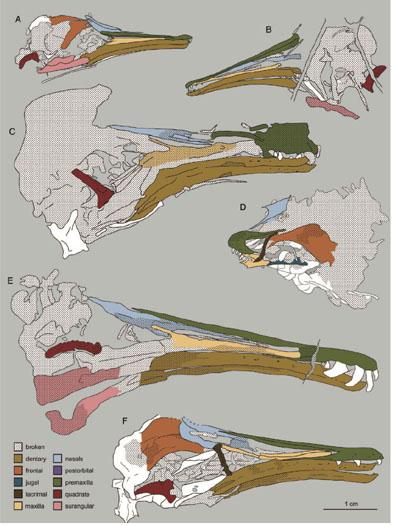

Fig.1: Camera lucida drawings of select enantiornithine skulls: A, Rapaxavis pani, DNHM D2522; B, Longirostravis hani, IVPP V1130; C, Longipteryx chaoyangensis, IVPP V 12325; D, Eoenantiornis buhleri, IVPP 11537; E, Longipteryx sp., DNHM D2889; F, Longipteryx chaoyangensis, IVPP V12552; G, .Shenqiornis mengi, DNHM D2951; H, Pengornis houi, IVPP 15336; I, Alethoalaornis agitornis, LPM 00009; J, Cathayornis yandica, IVPP V9769; K, Dapingfangornis sentisorhinus, LPM 00039; L, M, Gobipteryx minuta, IGM-100/1011, righl and left lateral views.(Image by O Connor JK)

Related News

Photos

More>>trade

- Conclusion Ceremony of the Workshop on Corruption Prevention of Asian and

- He Yong Stressed at the National Experience Exchange Conference of Deepening

- He Guoqiang Stressed at the First Session of the Joint Conference of Corruption

- NBPC Office Holds a Special Lecture on UN Convention Against Corruption and its

- National Experience-Sharing Conference on Deepening Government Affairs Publicity

market

- The Second Conference of States Parties to the United Nations Convention against

- Representatives of the Workshop of Corruption Prevention for Asian and African

- The Workshop of Corruption Prevention for Asian and African Countries Came Back

- He Yong Met With Representatives of the Workshop of Corruption Prevention for

- The Workshop of Corruption Prevention for Asian and African Countries Successful

finance

- The First Phase of Special Discussion of the Workshop of Corruption Prevention

- Students of the Workshop of Civil Servants of Hong Kong Visited NBCP

- Fujian convenes working conference on corruption prevention

- National Roving Seminar on PCT Held in Xi'an

- Shaanxi IP Administration Launches Patent Administrative Law-Enforcement