To save money, Fan Guoliang skips lunch, but not study, by Weiming Lake.

(Photos: Guo Yingguang)

Peking University, Mar. 3, 2011: Vegetable vendor Fan Guoliang sits in a class with 20 Peking University (PKU) undergraduates learning about the 305 poems in The Book of Songs.

"I know I look messy," Fan says, scratching his head and combing his hair with his fingers.

"I don't want to disgrace the university or disrespect the professor here."

Fan's 15-square-meter apartment at the base of Fragrant Hill has no heating or hot water yet.

"They will come and install the heating facility," Fan repeats every few minutes, "then I can shower and shave."

Yesterday the 52-year-old sat in on a class about the Analects.

At 14 years old, third-grade school dropout Fan left his village by Lanxi, a county-level city under the prefecture of Jinhua, Zhejiang Province and went to work in Jiangxi Province.

Back then Fan never could have imagined going back to school, let alone attending the top institute of higher education in China for classics. He is a more practical man.

When Fan came back to his hometown in 1977, he found his land had been taken by the local government. He survived by selling tofu and vegetables.

It was in 2008 when his family decided to renovate their ancestral grave that they unearthed something that forever altered the course of Fan's humble life.

Fan discovered he was the 28th generation descendant of Fan Jun, a prominent Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) scholar and teacher of Zhu Xi, a leading figure in Neo-Confucianism.

"Twenty out of the 250 jinshi (Forbidden City palace examination graduates) in Lanxi's history came from our family," Fan says.

"I would like to be able to understand the life story and works of my ancestor."

The former peasant now devotes all his spare time to researching the works of ancestor Fan Jun.

"I stopped having dinner with my wife," he says. "I always eat and study together."

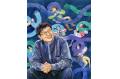

Vegetable vendor Fan Guoliang at class

Predicament

With few reading resources, Fan's research progressed slowly. Then in September 2010, he met Liu Zhe, a fellow villager on the Internet. Fan's predicament reminded Liu of his own.

Liu flunked the college entrance examination in 1989 and missed out on his limited chances of a higher education.

This Zhejiang Province peasant did not give up on his dream of becoming a writer and a researcher.

Fascinated by Cao Juren, a contemporary literary figure with a controversial political background, Liu sent out more than 100 letters to Chinese literature departments across the country.

Liu's letter caught the attention of Zhang Ligen, former administrative dean of PKU s Department of Chinese Literature.

"Liu had a good style of writing," Zhang says, "and his interest in research was sincere.

"It would be a pity if he stayed in the village as a peasant all the rest of his life."

Encouraged by Zhang, Liu came to Beijing in 1996 and was permitted to sit in on classes by Qian Liqun, a prominent scholar of contemporary literature.

Compared with Fan, Liu Zhe's first winter accommodation was even tougher.

He survived in an abandoned apartment without electricity or heating where "even the ink froze."

The bookish young Liu got a job as a manual laborer and later shifted bricks at demolition sites between classes.

Lucky

Liu feels lucky to be allowed to study at PKU.

"There are three jewels at PKU: the library, the courses and the academic lectures," Liu says.

Liu revels in the resources the university makes available to him.

Soon he will celebrate his 15th year "on the cusp of PKU," a nomenclature he proposed in 2001 to describe those who pursue scholarship at the university without ever enrolling.

By studying hard and sitting in on literature courses for more than a decade, Liu has succeeded in publishing more than 500 articles in newspapers and magazines.

Liu's intellectual thirst has expanded to embrace an ever-broader interest in history, philosophy and even business management.

Through endless efforts participating in students' associations and seminars, Liu has built up a network of friendships with PKU students, professors and staff. His next goal is to become a successful Confucian businessman, he says.

With a book recently published and media attention attracted to the struggles of these informal scholars on the cusp, the community of outsiders continues to grow at the university where Liu is like the information hub.

People come from all over the country to consult him on where to rent a cheap apartment, how to acquire a university library pass, dining card or syllabus.

The majority of this new cusp community have a concrete ambition to fulfill: To move from the edge as a sit-in student to eventually earn a seat at the lecture hall as a legitimate, fully qualified student.

Gambling

At Triangle Place, an information exchange on campus, advertising for cheap dorms and apartments are addressed to those who have come to PKU to try their luck at the graduate school entrance examination.

"I knew a grad student once who spent three years here preparing to get into grad school," says Wang Zongyu, a professor at Department of Philosophy and religious studies.

"When he finished the master's program, he spent another three years getting into the PhD program.

"It's like gambling and sometimes ideals can be illusions. The college entrance examination system has magnified the importance of higher education."

Computer science major Zhang Xiaodong regards the cusp phenomenon as a problematic tradition.

"Some classes offered by the Guanghua School of Management and Department of Psychology are full," Zhang says. "Because of the sit-in students, PKU students sometimes cannot get a seat."

While PKU opens its doors to destitute sit-in students, it also attracts Master's in Business Administration aspirants paying tuition of over 60,000 yuan a year: Parked in front of the library can be seen a BMW 5, a Mini Cooper and various types of expensive SUV.

"Academics used to lead the lifestyle of nobility," Wang says. "Like the Confucian saying: Rites do not extend to the common people.

"But now knowledge has become a kind of conspicuous consumption option. Well-off businessmen come to PKU for short-term training courses on business ethics, for example."

In a 2005 article, Professor Chen Pingyuan, dean of Department of Chinese Literature encouraged outsiders to pursue knowledge and research.

"An ideal university should be open to all citizens," he wrote. "Inequality in education is a form of societal injustice."

Chen also acknowledged that although PKU has a healthy academic environment, the institution is often viewed through rose-tinted spectacles. In reality, the historical glories of so-called "PKU spirit" can be a bit distracting, Chen wrote.

As the birthplace of the May Fourth Movement, PKU still enjoys renown among dewy-eyed Chinese mainland residents for its progressive history and as a pioneer in promoting science and democracy.

The broader reality today is a more practical, market-driven institution, although the university still cherishes its liberal intellectual tradition.

In the 1980s and 1990s, PKU was more a place where people came to change their identity, Wang explains.

"For example if you were a peasant, after education you would become a cadre."

Fan now enjoys a certain celebrity around campus, often accompanied by university staff or followed by reporters from local newspapers or state-run television.

"Maybe after all the coverage, I will get my land back when I return to my town," Fan murmurs.

Philosophy professor Wang harbors serious reservations and doubts about the academic interest of many involved in the cusp community attending university.

"Going to PKU can act as a cover for some other deeper desire," he says.

"In the old days, people sought material wealth, a career or peace of mind at the temple.

"In modern times, people look for the same things at a university, be they material or spiritual solaces."

Reported by: Wang Fanfan

Edited by: Arthars

Source: Global Times