Five Chinese women: Some are smart, rich, and running the show; others just want a piece of the booming economy.

THE MAOIST SLOGAN "WOMEN HOLD UP HALF THE SKY" has adorned the walls of buildings in China for more than 50 years. Indeed, the Communist Party's official support for women's equality has fostered a visible and growing cadre of educated and successful professional women. It has also helped undermine a 2,000-year-old mindset, dating back to feudal times, that women are inferior to men. Today women compete with men at the best universities. There's woman boss at China's largest steel company. And 1.5 million female entrepreneurs run small and medium-sized businesses, 98% of which, according to Lu Xiaofen, editor of China Women's Daily, turn a profit-"which shows we are good with money."

But apart from a lucky elite with MBAs and the ability to raise millions of dollars from foreign investors, the vast majority of women in the workforce in China don't have it so easy. "Most small-business owners have very little opportunity for growth," says Lu. "Government policies do not favor them, making it difficult to get approval for a loan." The success of a relatively small number of women masks deeper problems of discrimination, which begin in the crib. Boy babies are still prized more highly than girl babies. Maoist rhetoric notwithstanding, women are more likely to lose their jobs when state enterprises close down. And in the county side a disproportionate number of women are denied higher education. More and more of them, migrant workers from poor villages, flood into China's cities to fill the jobs at the bottom-a bottom occupied overwhelmingly by wonen.

Still, education and economic progress offer the best hope for Chinese women. And as the five examples featured in these pages show, from the factory floor to the boardroom, women are doing an outstanding job holding up their half of the economic sky.

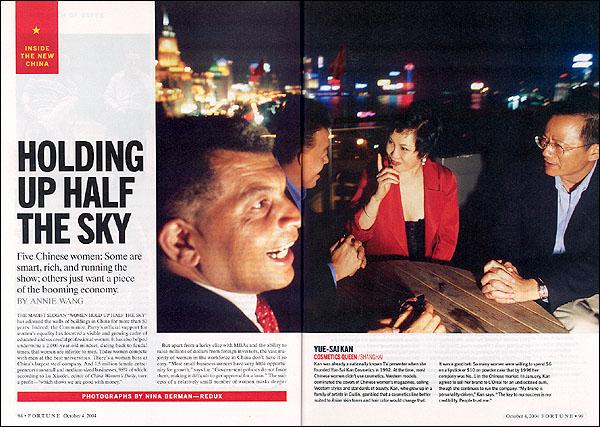

YUE-SAI KAN

COSMETICS QUEEN/SHANGHAI

Kan was already a nationally known TV presenter when she founded Yue-Sai Kan Cosmetics in 1992. At the time, most Chinese women didn't use cosmetics. Western models dominated the covers of Chinese women's magazines, selling Western styles and standards of beauty. Kan, who grew up in a family of artists in Guilin, gambled that a cosmetics line better suited to Asian skin tones and hair color would change that.

It was a good bet: So many women were willing to spend 6 on a lipstick or 10 on powder cake that by 1996 her company was No.1 in the Chinese market. In January, Kan agreed to sell her brand to L'Oreal for an undisclosed sum, though she continues to run the company. "My brand is personality-driven," Kan says. "The key to my success is my credibility. People trust me."

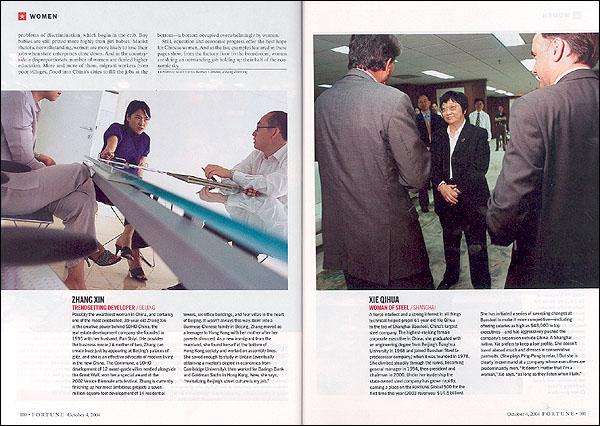

ZHANG XIN

TRENDSETTING DEVELOPER/BEIJING

Possibly the wealthiest woman in China, and certainly one of the most celebrated, 39-year-old Zhang Xin is the creative power behind SOHO China, the real estate development company she founded in 1995 with her husband, Pan Shiyi.(He provides the business moxie.) A mother of two, Zhang can create buzz just by appearing at Beijing's palaces of glitz, and she is an effective advocate of modern living in the new China. The Commune, a SOHO development of 12 avant-garde villas nestled alongside the Great Wall, won her a special award at the 2002 Venice Biennale arts festival. Zhang is currently finishing up her most ambitious project: a seven-million-square-foot development of 14 residential towers, six office buildings, and four villas in the heart of Beijing. It wasn't always this way. Born into a Burmese-Chinese family in Beijing, Zhang moved as a teenager to Hong Kong with her mother after her parents divorced. As a new immigrant from the mainland, she found herself at the bottom of Hong Kong society and worked on assembly lines. She saved enough to study in Britain (eventually obtaining a master's degree in economics from Cambridge University), then worked for Barings Bank and Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong. Now, she says, "revitalizing Beijing's street culture is my job."

XIE QIHUA WOMAN OF STEEL/SHANGHAI

A fierce intellect and a strong interest in all things technical helped propel 61-year -old Xie Qihua to the top of Shanghai Baosteel, China's largest steel company. The highest-ranking female corporate executive in China, she graduated with an engineering degree from Beijing's Tsinghua University in 1968 and joined Baoshan Steel (a predecessor company) when it was founded in 1978. She climbed steadily through the ranks, becoming general manager in 1994, then president and chairman in 2000. Under her leadership state-owned steel company has grown rapidly, earning a place on the FORTUNE Global 500 for the first time this year (2003 revenues: 14.5 billion).

She has initiated a series of sweeping changes at Baostel to make it more competitive-including offering salaries as high as 48,000 to top executives-and has aggressively pushed the company's expansion outside China. A Shanghai native, Xie prefers to keep a low profile. She doesn't travel abroad much and dresses in conservative pantsuits. (She Plays Ping-Pong to relax.) But she is clearly in command at a company whose executives are predominantly men. "It doesn't matter that I'm a woman," Xie says. "as long as they listen when I talk."

HONG HUANG

HONG HUANGPUBLISHING CHIC/BEIJING

If Hong Huang has her way, Chinese youth will identify more with Prada than with Mao. And as China's trendiest magazine publisher, she helps them point their feet in the right direction. Her office is a slice of downtown Manhattan in Beijing: an old factory stripped to floorboards and bare walls and full of beautiful people. From there Hong 43, publishes Time Out Beijing (she's launching a Shanghai edition too), a Chinese language Seventeen, and her flagship women's glossy, ILook,, through which she introduces her readers to Louis Vuitton handbags, Armani suits, and Gucci shoes. Hong may not have known designer labels growing up, but she did know privilege-her mother was a diplomat who taught English to the late Chairman Mao, and her stepfather was the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Partly educated in the U.S., Hong met her first husband in the States but soon left him-and later two other husband, She's certainly not shy about asserting her views on men, marriage, and sex, and her autobiography, A Wayward Girl From an Aristocratic Family, was a national bestseller. Today Hong believes that a dose of selfishness and materialism can be healthy-and change the thinking of future Chinese generations.

LI HONG

FACTORY WORKER/SHENZHEN

Even with seven roommates and countless fellow factory workers, Li Hong, 26, is very much alone. Her husband works at another factory two hours away, and her 8-year-old child lives with Li's parents back home in a small village in Henan province; she sees them once a year. Li and her husband communicate via phone calls and text messaging. (Her cellphone cost her 200-almost two months' wages.) It's not exactly what she dreamed of when she left home, but Li isn't complaining. A workday is usually eight hours long, 11 if the sweater factory is busy. She lives above the factory in a cramped room that serves as bedroom, bathroom, and closet for eight women, and she eats almost all her meals in an employer-subsidized canteen in the factory's courtyard. From the window of her room, Li can see Shenzhen's skyscrapers glittering in the distance. For fun? There's a park nearby where Li watches locals learn to dance. She manages to send home a little of the 115 she earns each month and hopes to save enough from what's left to one day return to her village for good. In the meantime, her family will have to wait.