"You wouldn't do a building like this for a developer in Australia. They'd just say, 'Let's make it vertical, let's make everything the same'. Here, people are not trying to find reasons not to do things. They're actually trying to find how to do it."

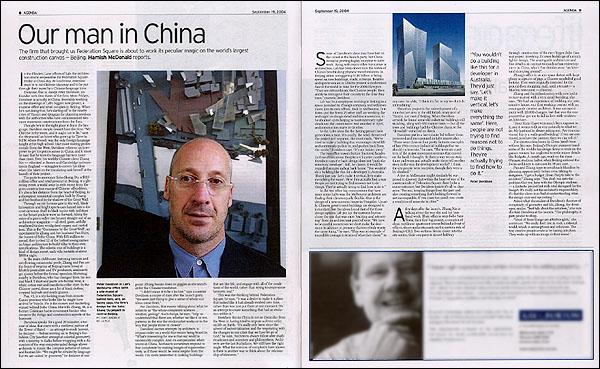

PETER DAVIDSON

Peter Davidson in Lab's Melbourne office (with a site model of Federation Square behind him). |

In the Flinders Lane offices of Lab, the architecture studio responsible for Federation Square, Friday is China day. At lunchtime, everyone stays in to eat Chinese takeaway and to be put through their paces by a Chinese language tutor. Everyone, that is, except Peter Davidson, co-founder with Don Bates of the firm. Most Fridays, Davidson is actually in China, feverishly working on the drawings of Lab's biggest new project, a massive office and retail complex in Beijing. When he's not doing that, he's darting off to the nearby cities of Tianjin and Qingdao for planning sessions with the authorities who have commissioned two more enormous constructions from the firm.

Though he's in the right place to learn the language, Davidson simply doesn't have the time. "My Chinese is the worst, and it ought not to be," says the 48-year-old architect who grew up in Taree in NSW, where French was the only foreign language taught at his high school. Like most visiting professionals from the West, Davidson relies on an interpreter to get his points across in China, and it must be said that he tests the language barriers more than most. Even his worldly Chinese client Zhang Xin - educated at Sussex and Cambridge universities in England - struggles to convey his ideas when she takes on the translating task herself at the launch of their project.

The party to announce Soho Shang Du, a $115 million office and retail precinct in Beijing, is a glittering event, a world away in style terms from the grim construction mania of Chinese officialdom. It's also a fair distance from the heart of Beijing, in a showpiece residential complex built by Zhang and her husband in the shadow of the Great Wall.

Through an old fortress-gate in the wall, black limousines and bright sports cars funnel into a discreet driveway. Staff in black tunics with red stars on the breast pockets wave us forward. Along the sides of a green valley rise houses straight out of an architecture magazine - all steel, glass, artfully weathered timber, verdigrised copper, and rusted iron.

This is the "Commune by the Great Wall", an experiment by Zhang and her husband Pan Shiyi, the bosses of Soho China. With $35 million to spend, they invited 12 of the hottest young names in Asian architecture to build villas to their own specifications. The eclectic mix of buildings is a kind of design resort, each villa rentable at about $800 a night.

In the main clubhouse, featuring terraces and overflowing ornamental pools, Zhang and Pan are the focus of swarms of Beijing's new breed of lifestyle journalists and TV producers, anxious to get quotes before the formal speeches. Hovering nearby is Davidson, who has changed from his normal black T-shirt and pants into formal wear, a white cotton suit and mandarin-collar shirt. In the Chinese crowd, there are a lot of black clothes, cropped haircuts and nerdy glasses.

Pan, 41, is a shy-looking man from remote Gansu province who looks like he might have arrived by bicycle. He is the money and marketing wizard behind Soho China. His wife Zhang, 38, is a former Goldman Sachs investment banker who oversees the design and construction aspects of the business.

Davidson speaks for a good 20 minutes, a torrent of ideas that starts with a medieval picture of the Tower of Babel - an attempt to reach heaven, he declares - before moving on to Beijing's Forbidden City (another attempt at celestial geometry), with a sidestep to Kafka before wrapping with a discussion of the way computer-aided design allows architects to mimic the complex patterns of nature and human life. "We might be divided by language but we are united by geometry," he declares at one point. Zhang breaks down in giggles as she searches for the Chinese translation.

"I didn't mean it to be a lecture," says a contrite Davidson a couple of days after the launch party. "We were just trying to give a sense of where our ideas come from."

The design for Soho China's latest project, Soho Shang Du in central Beijing. |

Davidson decries attempts by architects to impose order on a world that resists being boxed in. "What's interesting for me is that our world is undeniably complex. And it's compounded when you're in China. Architects sometimes respond to that complexity by making images of super-reductivity, as if these would be some respite from the world. I'm more interested in making buildings that are like life, and engage with all of the conditions of the world, rather than trying to create some hermetic seal."

This was the thinking behind Federation Square, he says. "It was a desire to make it a place that looked like it had already evolved over time, rather than was just put there at one moment. It's an attempt to create something that had an evolution within it."

Davidson thinks China is not so dissimilar from the West in having tried to impose a divine order on life on Earth. "It's really only been since the advent of industrialisation and the negotiating with the changes in our cities that we have let go of God," he says. "Architects always follow after mathematicians and scientists and philosophers. Architects are the last Euclydians. We still have the right angle. What the sciences of complexity have shown is there is another way to think about the relationship of elements."

Some of Davidson's ideas may have lost on the crowd at the launch party, but China overall is proving highly receptive to Lab's work. Along with many other top names in architecture, Lab has been drawn into the vortex of China's breathtaking physical transformation. In Beijing alone, a staggering $110 billion is being spent on new buildings, roads, subways, theatres and sports venues in a bid to present a modernised face to the world in time for the 2008 Olympics. "They are extraordinary, the Chinese people, their ability to re-imagine their country in the time they have," marvels Davidson.

Lab has four employees working in Beijing in a space provided by Zhang's company, and will soon move into its own offices. Back in Melbourne, Don Bates and the firm's 25 other staff are working day and night on design detail and documentation, to be shunted up to Beijing to meet extremely tight deadlines: the commission was awarded in April, and construction starts in October.

So far, Lab's ideas for the Beijing project have gone down a treat. Unusually, the retail element of the project isn't separate, like most malls. "We've tried to make a building that encourages street life and continually pulls it in, and pushes back from the inside," Davidson says. "It's not hidden away."

The two office towers feature fractured facades in three dimensions. Despite a 4.5 metre cantilever, Davidson says the basic design does not "push the structural envelope". Still, he claims, it would be regarded as quite radical back home. "You wouldn't do a building like this for a developer in Australia. They'd just say, 'Let's make it vertical, let's make everything the same'. Here they actually find a way. People are not trying to find reasons not to do things. They're actually trying to find how to do it."

In the two other big commissions that have since come Lab's way, the Melbourne architects are finding their clients equally flexible. One is the design of a new customs house in Hongdao. Usually, Chinese government buildings are designed to intimidate, but Davidson found that of the three design options Lab put up, the customs bureau chose the one that was most "exciting and interesting" from an architectural point of view.

"We have to be careful sometimes we don't make the decisions in advance or presume that everybody wants the same thing," he says. "This was an example of incredible courage in terms of what they chose." In any case, he adds, "I think it's fair to say we don't do intimidating".

The other project is the redevelopment of a nine-hectare area in the old British treaty port of Tianjin, just east of Beijing. When Davidson arrived, he found some old industrial buildings still standing, along with 950 mature trees - but all the trees and buildings had the Chinese character for "demolish" stencilled on them.

Davidson put in a last-minute bid to have them preserved and incorporated in Lab's masterplan. "These were three or four pretty fantastic examples of late 19th century industrial buildings that we should try to retain," he says. "The trees are a pattern of the major movement systems that existed on the land. I thought, 'Is there a way we can take those pathways and actually make them tell another story in the way the development works?' I think the city people were receptive, though they were a bit shocked."

Davidson put in a last-minute bid to have them preserved and incorporated in Lab's masterplan. "These were three or four pretty fantastic examples of late 19th century industrial buildings that we should try to retain," he says. "The trees are a pattern of the major movement systems that existed on the land. I thought, 'Is there a way we can take those pathways and actually make them tell another story in the way the development works?' I think the city people were receptive, though they were a bit shocked."A few in Melbourne might similarly be surprised to discover that within the heart of one of the masterminds of Federation Square there lurks a conservationist, but Davidson insists it's all in character. "For me, keeping things from the past and also creating something that's looking forward is not incompatible. If you erase too much you create a condition of amnesia in cities."

Afew days after the launch, Zhang Xin is talking about the way she and her husband work. Their office is atop Soho New Town, their first big project, a complex of clean rectilinear apartment towers behind a front of offices, shops and restaurants on the eastern side of Beijing's CBD. Two or three blocks closer into the city centre, their company is almost halfway through construction of the even bigger Soho Jianwai project, involving 23 tower buildings of a much lighter design. The avant-garde architecture and fine detail is in contrast to much urban redevelopment in China, which Pan derides as an "architectural dumping ground".

Zhang's office is an airy space dotted with large glossy sculptures of pigs, a Chinese symbol of good fortune. They were originally intended for the ground-floor shopping mall, until a tenant - a Muslim restaurant - objected.

Zhang and Pan's fascination with new architecture started with a very small building, she says. "We had an experience of building our own country house, our first working contact with an avant-garde creative architect. It was an experiment with 20,000 changes, but that was the one project that got me to fall in love with modern architecture.

"Since then I have very much been exposed to it, and it seems to fit in very naturally to what we do. My husband is always asking me, 'Are you convinced this is a really good building? If you are convinced, you have the passion, then we can sell it'."

The construction boom in China hasn't been without hiccups. Beijing's Olympic planners hired some of the world's top design firms to work on the games venues, but neglected to settle minor details like budgets. A month ago, work on the main Olympic stadium halted when Beijing ordered the Swiss architects to cut costs by 40 per cent.

Pan and Zhang hope to avoid such blunders by planning appropriately before even talking to designers. "I get a budget (from Pan) to take to the architect," Zhang says. "You don't run into the problem that you have with the Olympic stadium - a fantastic project but with total disregard for the budget. It's really not the architect's responsibility, it's that the client is so bad at understanding what the design may end up costing."

Asked what she makes of Davidson's theories of complexity, of geometry and life, Zhang, the developer, smiles. "Just talk about the intuition," she says she told Davidson at the launch. "The philosophy, it puts people to sleep.

"Most of these things are afterthoughts," she continues. "We really don't live in such a rational world, which is assumptions and solutions. The way creative people create is by having intuition. They wake up with an image in their mind."