"Experiment is the character of China today-from the economic system to the political system to the way of living, the way of doing business, everything is happening for the first time. And that spirit is carried out into the urbanization process," says Zhang Xin. "If you look at [new buildings in] Shanghai, they were mostly designed by what we call the big American design firms, with good quality but rather banal modern architecture,Beijing is taking a different route. The top avant-garde architects are working in Beijing and their work will represent a different quality of city outlook."

Beijing's unprecedented Building boom will transform the cityscape by the opening of the 2008 Olympic Games. And with some of the west's most influential and avant-garde designers behind the projects, the skyline promises to be spectacular. But even as locals wait for the wonders to emerge, critics are asking: 'What price, Progress?'

In the 14th century, the master builders of Beijing constructed an imperial city along cosmological principles, centred on an axis made up of the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven and the Temple of the Sun, a metropolis imbued with symbolic meaning. Clustered around the imperial core were the hutongs, the warren of laneways composed of siheyuan, the walled courtyards where the people of the Northern Capital lived. It has remained much that way since Until now.

Old Beijing is being transformed dramatically. Spurred by the 2008 Olympic Games, new China is imposing a modern high-rise metropolis of glass, steel, concrete and titanium on the old gird of the imperial city. The world's brightest and boldest avant-garde architects, mostly from the west, have been commissioned to shape Beijing's future. The effects will be startling. By 2008, 19 new buildings will have reshaped the cityscape.

The wave of construction is reminiscent of the frenzy of cathedral building in Europe's major cities in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. The Games will change the way Beijing looks forever, bringing as fundamental an urban transformation to the Chinese capital as the cathedrals did to Chartres, Paris and Florence. Rumour and innuendo are swirling around these projects in much the same way as they surrounded the building of the great edifices of Canterbury and Strasbourg, when whispers of master builders with arcane ways, ecclesiastical excess and dark forces accompanied the back-breaking construction of the Gothic symbols of power in Europe.

On the mainland, there is talk the money has dried up for Rem Koolhaas' building for state broadcaster CCTV and funding for Jacques Herzog and Pierre de suggest CCTV has abandoned the project because it will not be ready in time for the Olympics, when the wyes of the world would be on it. Then there are unfounded rumours the huge CCTV building is so structurally complex the engineers cannot build it. And yet another whisper says the district government, which owns the site, has cold feet about giving so much land and face to a government broadcaster, preferring instead the BBC's more modest combination of a downtown studio and large, suburban production facilities.

The gossip is proof that something fundamental is happening to Beijing's skyline. This kind of construction normally happens only after a war. Marco Polo said of medieval Beijing that there was "so great a number of houses and people, no man could tell the number". He should take a look in four years, when the 19 Olympic projects are finished, creating some of the world's most spectacular buildings. Transforming Beijing is a test of endurance worthy of the Games themselves: 300,000 city residents have been officially relocated and normal city life is regularly put on hold to make way for the building boom. This is not a facelift; this is a US 75 billion regeneration. Even familiar landmarks-the Forbidden City, the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace, the Ming Tombs and the Great Wall-are being spruced up for the Games.

"Experiment is the character of China today-from the economic system to the political system to the way of living, the way of doing business, everything is happening for the first time. And that spirit is carried out into the urbanization process," says Zhang Xin, a Beijing native who grew up in Hong Kong and London. With her real-estate-developer husband Pan Shiyi, Zhang runs her company SOHO China, regarded as one of Asia's most progressive. In the past few years, SOHO has built two huge housing and commercial projects and last year won a Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale for a series of eclectic villas, called Commune, along the Great Wall. Zhang has just given British-born Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid one million square metres to create a futuristic swarm of residential blocks.

"Experiment is the character of China today-from the economic system to the political system to the way of living, the way of doing business, everything is happening for the first time. And that spirit is carried out into the urbanization process," says Zhang Xin, a Beijing native who grew up in Hong Kong and London. With her real-estate-developer husband Pan Shiyi, Zhang runs her company SOHO China, regarded as one of Asia's most progressive. In the past few years, SOHO has built two huge housing and commercial projects and last year won a Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale for a series of eclectic villas, called Commune, along the Great Wall. Zhang has just given British-born Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid one million square metres to create a futuristic swarm of residential blocks.From the Olympic Stadium (top left and top) to the CCTV complex (left) and a futuristic residential complex (above), Beijing's planned buildings have captured the public's imagination-and angered critics.

The firm's CBD headquarters are in a precinct of new white towers with abundant glass. Zhang's interest in the artistic side of building is evidenced by the catalogues scattered around the office, attesting to exhibitions by Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol. She says Beijing is the only Asian city introducing so much unconventional architecture to its landscape.

"If you look at [new buildings in] Shanghai, they were mostly designed by what we call the big American design firms, with good quality but rather banal modern architecture," she says. "Beijing is taking a different route. The top avant-garde architects are working in Beijing and their work will represent a different quality of city outlook."

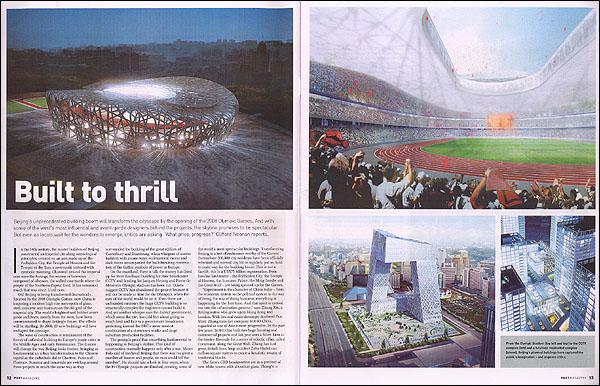

The Olympic Stadium (above and below) has been described by its designers as "like a bird's nest with its interwoven twigs".

"I THINK THE CHINESE PEOPLE UNDERSTAND THAT IT'S A STRENGTH TO OPEN THEMSELVES [UP] AND TO ASK PEOPLE FROM THE OUTSIDE TO WORK[THERE]"

Central to the city's transformation are vast jnfrastructural upgrades. One of the main avenues in Beijing, Dongzhimen, will have a new 800,000-square metre railway station, which will be the terminus of the future express railway to Beijing airport, as well as a connection to the subway network, a covered bus depot and a residential and office development.

Andrew Chan, managing director of consultants Davis Langdon & Seah, which conducts quantity surveying on many of the new buildings, says the boom is driven by factors other than the Olympics. "There is the effect of China joining the World Trade Organisation. Developers are foreseeing demand for commercial space and they are optimistic about facilities related to WTO," SAYS Chan.

"Shanghai is ahead of Beijing by AT LEAST 20 years in construction, which means Beijing has huge space for development, Beijing has a very goof future. Most economic cycles usually only last a certain time, but the Beijing building boom could last 10 or 15 years for several reasons. As well as the WTO, you have the Olympic Games, which will keep stimulating Beijing's development. Then the government strategy is to make the economy have healthy growth, so all this should make the cycle longer. There are some problems too pollution, water shortages and corruption are always a headache for the foreign investor. But it is improving."

The influential journal Building Design recently published a list of the top five power brokers in world architecture and four of the five people named are either building in Beijing or in some way linked to its revolution in urban rejuvenation. The list includes Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss-based duo who renovated a London power station to create the Tate Modern in 2000 and built an 80 million Prada store that opened in Tokyo this year. Herzog and de Meuron are building the centre-piece of the Beijing Games, a huge bird's nest structure that will be the Olympic Stadium. It promises to become the icon of the event, with 100,000 seats afterwards.

"The stadium's appearance is pure structure," says the firm. "Fa?ade and structure are identical. The structural elements mutually support each other and converge into a grid-like formation-almost like a bird's nest with its interwoven twigs. The spatial effect of the stadium is novel and radical yet simple and of an almost archaic immediacy, thus creating a unique historical landmark for the Olympics2008."

The influential journal Building Design recently published a list of the top five power brokers in world architecture and four of the five people named are either building in Beijing or in some way linked to its revolution in urban rejuvenation. The list includes Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss-based duo who renovated a London power station to create the Tate Modern in 2000 and built an 80 million Prada store that opened in Tokyo this year. Herzog and de Meuron are building the centre-piece of the Beijing Games, a huge bird's nest structure that will be the Olympic Stadium. It promises to become the icon of the event, with 100,000 seats afterwards.

"The stadium's appearance is pure structure," says the firm. "Fa?ade and structure are identical. The structural elements mutually support each other and converge into a grid-like formation-almost like a bird's nest with its interwoven twigs. The spatial effect of the stadium is novel and radical yet simple and of an almost archaic immediacy, thus creating a unique historical landmark for the Olympics2008."The bird's nest description has struck a chord with Beijingers, who refer to it as such. The 500 million stadium has a grey exterior and red interior(inspired by the colours of traditional courtyard homes), and a roll-on roof to protect against summer rain. It looks like a ball of string lit from behind. The design was chosen overwhelmingly by an international jury over finalists from China and Japan and there was anger at the decision to import overseas talent.But some academics maintain home-grown architects are not ready to take on the tougher agendas of contemporary architecture from social to technological issues, and need to grow out of the Beaux-Arts and Soviet styles commonly taught in architecture schools.

"I think the Chinese people understand that it's a strength to open themselves [up] and to ask people from the outside to work [there]," Pierre de Meuron said recently Jacques Herzog wants the building to be in the tradition of great Chinese architecture. "And we also wanted something that would be structure, space and ornament at the same time," Herzog said "We were inspired by antique Chinese ceramic vases with cracks. And that's why it has a bird's nest structure too."

Next in the Magazine's list is China's President Hu Jintao. "Hu has unrivalled power in the world to hire the best architects on the biggest and boldest projects available anywhere And he takes a real personal interest," the journal wrote. "His Expansionist and outward-looking policies are fuelling an exploding marker for western architects as China transforms from a largely rural economy into an industrialized nation of 1.3 billion souls."

Then comes Sir Norman Foster, Foster, familiar to Hong Kong for his much-admired Chek Lap Kok airport terminal and the landmark HSBC headquarters, and also named as a contender to build a huge roof over the proposed Cultural Centre for West Kowloon. Foster will do for Beijing's Reichstag when he builds a second terminal there, modelled on the mythical Chinese dragon, with a shining red body and yellow-green tail.

No list of movers and shakers in architecture is complete without Dutch iconoclast Koolhaas, who has become known, flippantly, as the Sid Vicious of contemporary architecture. His project for CCTV, despite the rumour mill, will be one of the truly amazing buildings of the construction boom. Some have labelled the structure a "twisted doughnut"; a huge, 1980s-styled, brightly coloured letter Z. It will be 230 metres high, a continuous loop without right angles and is due to be finished by 2007. A companion building next door is shaped like a big boot and will provide more than 500,000 square metres of studios, offices, exhibition space and a hotel. It is located in an earthquake zone and is designed to withstand a "level three" earthquake-expected once every 2,500 years.

Koolhaas is a gifted theorist, a cultured iconoclast who founded the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in London in 1975, He has been compared with fellow designer Le Corbusier for his willingness to tackle the big issues in world architecture today. "Architecture," Koolhaas has said, "is a hazardous mixture of omnipotence and impotence." In a profession known for producing eccentric geniuses, Koolhaas has legendary status. The list of Koolhaas buildings may not be long but what he has built is highly impressive: the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam, the Educatorium student centre in Utrecht and a house for a severely disabled man in Bordeaux. His credentials as the world's coolest architect are impeccable: the constant traveling; the popularity of his books with intellectuals all over the world; his teaching job at Harvard.

Ole Scheeren, the OMA partner in charge of the CCTV project, points out half the team is Chinese, with 20 of them working in OMA's Rotterdam offices. "The project is a combined effort of the two cultures rather than a product developed in the west and just shipped over to China" he says. "That has never happened before. Working on this project has been really interesting for us."

Also set to feature on the skyline is Frenchman Paul Andreu's contentious National Theatre, dubbed variously as the "duck egg" or the "eggshell", which is due to open diagonally opposite the Forbidden City next year. The theatre will cover nearly 119,000 square metres in the heart of Beijing next to Tiananmen Square. The shell is made of titanium and glass and will be lit by different coloured lights at various times of the day.

Sir Norman Foster's design for Beijing's new airport terminal (above and below) is based on the mythical Chinese dragon, with its shiny red body and yellow-green tail.

Then there is the 120million Olympic swimming stadium, dubbed the Water Cube, built by Ove Arup Engineering Group in collaboration with the Shenzhen Design Institute. Experts say it represents a construction challenge. The building's rectangular frame supports a complex web, which apparently is inspired by the patterns made by soap bubbles. Arup says the design, by Australian firm PTW, has evolved to allow ease of construction.

Some local architects are concerned the introduction of foreign ideas will erase much of what is intrinsically Chinese about the city, while developers make a quick buck. Zhou Rong, who teaches at Beijng's Tsinghua University, is one critic.

"CITIES ARE VERY LIKE HUMAN BEINGS.WOULD YOU BE PREPARED TO GIVE UP ALL YOUR MEMORIES AS THE PRICE FOR DRIVING A MERCEDES-BENZ? PROBABLY NOT. SO WHY DO WE ALLOW THIS HAPPEN TO OUR CITY"

Paul Andreu's National Theatre (above), dubbed the "duck egg" by locals, and the stunning "water cube" swimming stadium (below).

"Cities are very like human beings. Would you be prepared to give up all your memories as the price for driving a Mercedes-Benz? Probably not. So why do we allow this happen to our city?" says Zhou. "Some of what's happening on these sites cuts off the city's memory. Beijing is losing its cultural and historical sense. Its Chinese characteristics are lost. Going by the rate at which Beijing is losing its hutongs-about 900 a year-there will hardly be any hutongs left by 2008. If Beijing keeps developing at this speed, it will become an extremely flat city with no sense of historical depth."

The leveling of the hutongs-and the relocation of the communities that live in them-is a sensitive issue. Many people see their destruction as the destruction of a way life. There have been reports of developers ignoring protection orders on buildings, evicting residents and knocking down the old buildings that were supposed to be retained. In February, Beijing mayor Wang Qishan admitted there had been illegal demolitions and evictions.

Nevertheless, Zhou welcomes some of the new buildings and seems happy with the freedom of expression they symbolize after so many years of Beaux-Arts and Soviet-style architecture. "I like some of the new buildings: the state opera house, the new CCTV tower, especially the Olympic 'bird's nest'-that's one of the finest examples of modern architecture in the world," he says.

Professor Wu Yaodong, of the Tsinghua Architecture and Design Institute, regrets a Chinese architect's design was not chosen for the national stadium, but he is pleased the mainland's building industry is opening up to new ideas and methods. "Introducing new construction designs to China shouldn't necessarily be in competition wirh maintaining traditional Chinese characteristics. We should learn from our foreign counterparts, from their good methods," says Wu.

Either way, it looks increasingly as if those in favour of the skyscrapers have won the argument over whether or not Beijing should be a high-rise city. Chinese-born architect, I. M. Pei, on a visit to Beijing a few years age, bemoaned the quest to build ever higher, "I said long ago, you should be able to look out over the walls of the Forbiden City and see nothing but blue sky. Of course, now it's grey sky, buy see sky."