By John Ridding, Editor and Publisher, Financial Times Asia

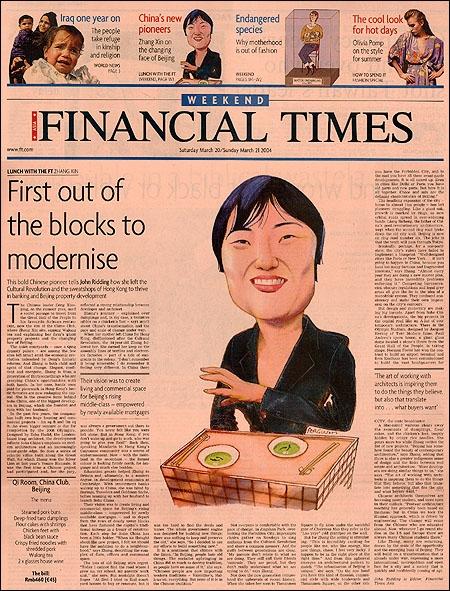

This bold Chinese pioneer tells John Ridding how she left the Cultural Revolution and the sweatshops of Hong Kong to thrive in banking and Beijing property development.

The Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, so the rumour goes, used a secret passage to travel from the Great Hall of the People to his favourite Sichuan restaurant, now the site of the China Club, where Zhang Xin sits, sipping Wulong tea and explaining her firm's giant property projects and the changing face of Beijing.

The quiet courtyards - once a Qing dynasty palace - are among the few sites left intact amid the economic revolution unleashed by Deng's historic reforms. And Zhang is both child and agent of that change. Elegant, confident and energetic, Zhang is from a generation of 30-somethings who are grasping China's new opportunities with both hands. In her case, hands once paid for piecework in Hong Kong's hectic factories are now reshaping the capital. She is the creative force behind Soho China, one of the biggest developers in Beijing, which she founded and runs with her husband.

In the past few years, the company has built two huge housing and commercial projects - 5 million sq ft and 7 million sq ft. An even bigger venture is due for completion by the 2008 Olympics. Designed by Zaha Hadid, the London-based Iraqi architect, the development reflects Soho China's emphasis on modern architecture and an increasingly avant-garde edge.

So does a series of eclectic villas built along the Great Wall, for which Zhang won the Silver Lion at last year's Venice Biennale. It was the first time a Chinese project had participated and, for the jury, reflected a strong relationship between developer and architect.

Zhang's journey - explained over dumplings and, in my case, a tentative nibble on a chicken's foot - says much about China's transformation and the pace and scale of change under way.

When her mother left China for Hong Kong, disillusioned after the Cultural Revolution, the 14-year-old Zhang followed her. She earned her keep on the assembly lines of textiles and electronics factories - part of a tide of emigrants to the colony. "I don't remember it being miserable; I do remember it feeling very different.

In China there was always a government out there to provide. You never felt like you were left alone. But in Hong Kong, if you don't wake up and go to work, who was going to give you food?" Back then, speaking Mandarin in Hong Kong's Cantonese community was a source of embarrassment. Now - with the mainland in the ascendant - the former colony is looking firmly north, for language and much else besides.

Education grants helped Zhang to Britain and, ultimately, to an MPhil in development economics at Cambridge. With the world's investment banks waking up to China, she was hired by Barings, Travelers and Goldman Sachs, before teaming up with her husband to launch Soho China.

Their vision was to create living and commercial space for Beijing's fast-rising middle-class - empowered by newly available mortgages - and to depart from the rows of dowdy tower blocks that have flattened the capital's traditional hutongs in a frenzy of construction. Each step for Soho China has been a little bolder. "When we thought about the new project, I felt we should have the ambition to do a neighbourhood," says Zhang, describing the complex of apartments, offices and communal space.

The loss of old Beijing stirs regret. "Today I cannot find the road where I grew up, my school, my parents' work unit," she says. But nostalgia doesn't linger. "At first I tried to find courtyard houses to buy or renovate, but it was too hard to find the deeds and leases. The whole government engine was designed for building new things; there was nothing to keep and preserve the old," she says. "So I decided to use my efforts to build something new."

It is a sentiment that chimes with the times. "In Beijing, people hate old things. The socialist upbringing in China did so much to destroy tradition, so people have no sense of it," she says. "Chinese people are now importing western traditions - Valentine's, Halloween, everything. But none of it is in the Chinese tradition."

Not everyone is comfortable with the pace of change. In Jingshan Park, overlooking the Forbidden City, impromptu choirs gather on Sundays to sing anthems from the Cultural Revolution and share a common memory. And the gulfs between generations are clear. "My parents don't relate to what we are doing. They still call their friends 'comrade'. They are proud, but they don't really understand what we are trying to do," says Zhang.

Nor does the new generation comprehend the upheavals of recent history. When she takes her sons to Tiananmen Square to fly kites under the watchful gaze of Chairman Mao they refer to the "Lao yeye" (old grandpa) on the wall.

But for Zhang the setting is stimulating. "This is incredibly exciting for people like me, who like energy, like new things, chaos. I feel very lucky. I happen to be in the right place at the right time." And from this upheaval emerges an architectural pattern to match. "The urban- isation of Beijing is unique," she says.

"On the one hand you have this kind of Russian, communist style with wide boulevards and Tiananmen Square; on the other side you have the Forbidden City, and to the east you have all these avant-garde developments. It is all mixed up. Even in cities like Delhi or Paris you have old parts and new parts.

But here it is all together. Chaos and mix are the defining characteristics of Beijing."

The headlong expansion of the city - now home to almost 14 million people - has left planners struggling in its wake. Like a giant oak, growth is marked by rings, as new orbital roads spread in ever-widening bands. Liang Sicheng, the father of China's post- revolutionary architecture, wept when the second ring road broke down the old city wall. Beijing is now on ring road number six. The joke is that the tenth will pass through Tokyo.

Ironically, perhaps, for a one-party state, the city's rulers have failed to implement a blueprint. "Well-designed cities like Paris or New York. it isn't going to happen in China, because you have too many factions and fragmented interests," says Zhang. "Almost every year they are doing a new master plan, and they have incredible problems enforcing it." Competing bureaucracies, obscure regulations and legal grey areas all give the lie to the idea of a monolithic system. They confound consistency and make their own impression on the city's contours.

But design and modernity are making big inroads. Apart from Soho China's developments, the major projects under way in the capital read like an A-list of contemporary architecture. There is the Olympic Stadium, designed by Jacques Herzog of Tate Modern fame. Paul Andreu's new opera house, a giant glass dome located a stone's throw from the Great Hall of the People, is taking shape. Norman Foster has won the contract to build a new airport terminal and Rem Koolhaas has been commissioned to build the vast new headquarters for CCTV, the state broadcaster.

A Mao-suited waitress clears away the remnants of dumplings, flour cakes, and the chicken's foot, ineptly hidden by crispy rice noodles. She pours more tea while Zhang recites the list of new projects. "Beijing has somehow found the beauty of contemporary architecture," says Zhang, adding that there is also a greater indigenous sense of design and the links between real estate and architecture.

"More developers are doing similar things to us," she says. "The art of working with architects is inspiring them to do the things that they believe, but also that translate into something that fits the city and what buyers want."

Chinese architects themselves are becoming more modern, and more open in their outlook. "Post-war architecture teaching has generally been based on Bauhaus. But in China we took the Russian approach, which is driven by engineering. The change will come from the Chinese who are educated abroad. Now, whenever I go round studios in the US and Europe there are always many Chinese students there."

Like Zhang, many are returning, drawn by the scale of the opportunity and the emerging buzz of Beijing. They will build on a transformation that is already under way, expressing a more international, metropolitan and open face for a city and a society that is quickly and confidently coming of age.