by Mark Graham

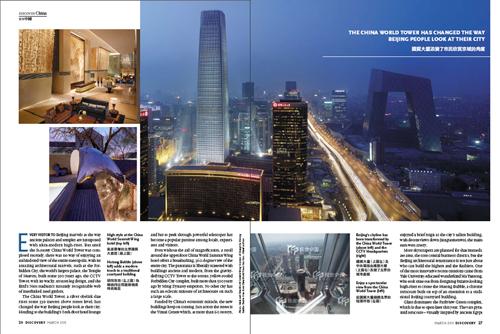

Every visitor to Beijing marvels at the way ancient palaces and temples are juxtaposed with ultra-modern high-rises. But until the 81-storey China World Tower was completed recently, there was no way of enjoying an unhindered view of the entire metropolis, with its amazing architectural marvels, such as the For-bidden City, the world s largest palace, the Temple of Heaven, built some 500 years ago, the CCTV Tower, with its wacky, trouser-leg design, and the Bird s Nest stadium s instantly recognisable web of interlinked steel girders.

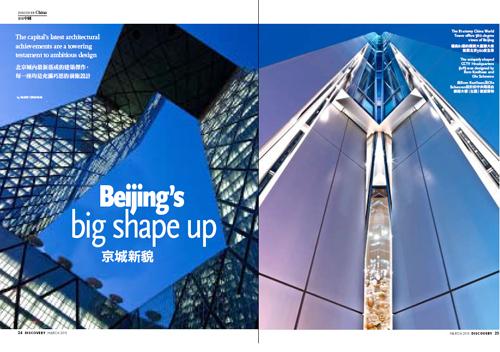

The China World Tower, a silver obelisk that rises some 330 metres above street level, has changed the way Beijing people look at their city. Heading to the building s 80th-floor hotel lounge and bar to peek through powerful telescopes has become popular pastime among locals, expatriates and visitors.

Even without the aid of magnification, a stroll around the upper-floor China World Summit Wing hotel offers a breathtaking, 360-degree view of the entire city. The panorama is liberally scattered with buildings ancient and modern, from the gravity-defying CCTV Tower to the serene, yellow-roofed Forbidden City complex, built more than 500 years ago by Ming Dynasty emperors. No other city has such an eclectic mixture of architecture on such a large scale.

Funded by China s economic miracle, the new buildings keep on coming. Just across the street is the Yintai Centre which, at more than 60 storeys,enjoyed a brief reign as the city s tallest building, with decent views down Jianguomenwai, the main east-west artery.

More skyscrapers are planned for that immediate area, the core central business district, but the Beijing architectural renaissance is not just about who can build the highest and the flashiest. One of the most innovative recent creations came from Yale University-educated wunderkind Ma Yansong, who took time out from designing bizarre-looking high-rises to create the Hutong Bubble, a chrome structure built on top of an extension to a tradi-tional Beijing courtyard building.

Glass dominates the Parkview Green complex, which is due to open later this year. The vast pyra-mid structure visually inspired by ancient Egypt rather than imperial China claims to be one of the most eco-friendly buildings in the city, using only half the energy of a similar-sized conventional office building. This feat is achieved by its double-glass exterior which can store thermal energy.

The four Parkview Green office towers are housed inside the giant pyramid, along with restaurants and shops. Dotted around the complex will be more than 40 sculptures by Salvador Dali, known as the Clot Collection, created by the Spanish surrealist late in life.

Also inside the complex will be a boutique hotel with 100 suite-sized rooms, courtesy of complex owners, the Hong Kong-based Parkview Group, which also has hotels in Singapore and France.

Farther north, a 10-minute drive away, is the Sanlitun Soho office-and-shopping complex in Beijing s buzzing Sanlitun district. Renowned Japanese architect KengoKuma, who also designed the nearby Opposite House hotel, a minimalist marvel, says he was striving to make the buildings as harmonious as possible with plenty of water features and greenery. The nine gleaming towers of Sanlitun Soho are arranged around a sunken pedestrian precinct which has a babbling brook running through it a relaxing contrast to the always-bustling main street above.

Once renowned for its dive bars, Sanlitun has evolved into the most vibrant part of the city. The scruffy, cheap-beer outlets have been joined by the Village shopping, dining and entertainment complex that shows malls do not have to be sterile and uniform. The latest section to open, Village North, offers generous, open public spaces and sunken piazzas, and is designed to stage outdoor summer entertainment, a novelty in Beijing

where developers are normally parsimonious when incorporating public space into their schemes. The design is based loosely on the siheyuan style, which is found in the older parts of the capital, where entire families live in rooms arranged around a central courtyard.

It is a neat nod to the past in a city that is heading to the future at breakneck speed. What makes the recent building boom in Beijing so remarkable is that nothing much of significance had happened, architecture-wise, for the past 50 years, since the grimly utilitarian Great Hall of the People was built in Tiananmen Square. Then came the successful Olympic Games bid, sparking a building frenzy that saw the city change more in five years than the previous 500.

As Beijing continues to look to the future, there is no sign of it abating yet.