This fall was a critical time for Loblaw Cos. Ltd.'s fledgling Joe Fresh Style apparel line. The grocer had been expanding its low-cost chic fashions to more superstores and beyond adult clothing to children's wear and lingerie. But while the retailer was touting such items as its trendy wrap jackets ($29) on its website, customers couldn't always find them at the store. Products were arriving at Loblaw superstores weeks, and sometimes more than a month, late.

“It's a good problem and a bad problem,” designer Joe Mimran, 54, said this week at his white-hued downtown Toronto studio in a converted microbrewery.

“It's been tough. … You can't let them [customers] down too often.”

Loblaw's systems are vastly improving now, Mr. Mimran insists, but it's an unusual spot for a celebrity fashion designer to find himself in. He's working for a grocery chain producing cheap chic. His Joe formula – a cornerstone of Loblaw's turnaround strategy – is taking off.

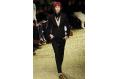

Joe Mimran in the Joe Fresh showroom. (Charla Jones/The Globe and Mail)

And yet he has been drawn into Loblaw's problems of getting merchandise to store shelves on time.

“It's a very, very promising line,” said Kaileen Millard-Ruff, fashion director at market researcher NPD and a keen Joe customer.

“But one of the biggest challenges has been getting product to the floor,” she said.

“Imagine what they could do if they could have the inventory where they want it, when they want it? It's nasty.”

David Howell, president of consulting firm Associate Marketing International, said he dropped by a Loblaw superstore in Mississauga last Wednesday afternoon – less than two weeks before Christmas – and the Joe section was three-quarters empty. By the end of the week, the shelves were well stocked.

There's a lot riding on getting Joe just right at Loblaw.

Galen G. Weston, the 34-year-old executive chairman of Loblaw and scion to the controlling Weston family, has vowed that the Joe products will reach $1-billion in annual sales by 2010. The retailer's apparel sales are targeted at $400-million by the end of this fiscal year – just 21 months after the Joe launch.

The company has plans to eventually branch out into Joe jewellery, cosmetics, fragrances and eyewear – all products, along with apparel, that carry higher profit margins than groceries.

It's foreign territory for a Canadian grocer to step into the cheap-chic fashion realm. Loblaw is taking a page from its nemesis, giant discounter Wal-Mart Stores Inc., which is rapidly expanding onto Loblaw's food turf in Canada.

Just as Joe apparel is named after its chief designer, Wal-Mart's Asda division in Britain had years earlier developed a trendy clothing line called George, named after its designer George Davies. It followed the fast-fashion recipe of quickly, and cheaply, copying designer runway styles for a mainstream consumer.

But while Wal-Mart's strength is distribution – getting products to the shelves on time – apparel has been a sore spot. For Loblaw, it's now an area in which it can shine, if it can fix its logistics, Mr. Howell said.

Dressed in a custom made dark plaid jacket, silver hair slicked back, Mr. Mimran is ready to apologize – but for the logistics, not for failing to meet demand. “If we're sold out, we're sold out. That's a good thing. I'm not going to apologize for that. Having the goods there at the right time when the consumer needs to have them, that I do apologize for and that is something obviously that we have to work harder to do.”

He predicted that the apparel operations would be, if not 100-per-cent, then 95-per-cent on track for the spring season, and already have been transformed.

And while he's pleased with the sales, especially in women's apparel, the revenue could have been a fairly significant number if systems were running smoothly, he said.

Part of the shift will come from the impact of about 40 employees on his team having recently moved to his downtown studio from Loblaw's Brampton, Ont., office 37 kilometres away. It symbolically consolidates all design activity with Mr. Mimran, for both Joe Fresh and Loblaw's President's Choice home products.

Having control of the brand is paramount for him. “In our industry if you try to do too much by committee you can end up with a very watered down notion of what the brand is.”

By all accounts, Mr. Mimran was a perfect choice of the wealthy Weston family to add flair to its grocery aisles. He already had ties with the family, having created private label styles for its high-end Holt Renfrew chain and President's Choice home decor products for Loblaw.

Known for a minimalist style, Mr. Mimran made his mark as co-founder in 1985 of Club Monaco, the hip fashion chain which was one of the original fast-fashion practitioners. Club Monaco was sold in 1999 to New York-based Ralph Lauren, and Mr. Mimran was shown the door about a year later when the financial results weakened amid an expansion.

His life has picked up tremendously since then. He and his second wife, designer Kimberley Newport-Mimran, 39, have become something of a power couple in Toronto.

He's got a hand in the upscale fashion world. He helped develop his wife's critically acclaimed Pink Tartan line, which sells at Holt's and prominent U.S. department stores such as Bloomingdale's – a far cry from cheap-chic Joe Fresh at Loblaw. And he's a partner with his long-time friend and associate Paul Sinclaire in another high end line called Tevrow + Chase (the middle names of Mr. Sinclaire and Mr. Mimran's youngest child) that they launched two years ago.

But Loblaw is his key focus these days. Being involved in the premium segment “gives us more fashion exposure,” he said. “We're much more able to predict, spot and respond to trends, which is a great competitive advantage. Having broad experience and broad perspective is a benefit in whatever role in life you choose. Why limit yourself?”