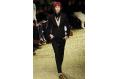

A model presents a creation by German designer Tomas Maier for Bottega Veneta

Since the 1960s explosion of jeans and hippie culture, which made gloves look hopelessly outdated, they have languished on the sidelines of fashion, but that is now definitely set to change.

Forget practicality, gloves are making a comeback as an affordable fashion accessory -- far, far cheaper than the "brag" bags sported by the wives and girlfriends of footballers.

Designer Manuel Rubio says what today's new young clientele want is originality: gloves have become "a fashion object, an object of desire."

"The days of traditional utilitarian gloves in black and brown to keep out the cold are long gone."

A model displays a creation by Italian designer Ettore Billotta

Rubio and partner Nadine Carel were approached by Olivier Causse, great-grandson of the founder of France's oldest glove-makers Causse, founded in 1892, to breathe new life into the family firm in the village of Millau, in the Aveyron region of southwest France.

Millau has been since the Middle Ages the world's centre of glove-making. There is an impeccable logic as to why: in a word, Roquefort. To supply the ewes' milk needed to make the famous blue cheese, lambs were slaughtered soon after birth when their pelts were too small to be turned into anything bigger than a pair of gloves.

In its heyday Millau turned out nearly five million pairs of gloves a year and exported all over the world, but in the 1960s glove-making went into free-fall because of radical social changes.

Karl Lagerfeld is seen during a press conference

The corner was turned in the mid 1990s, Rubio believes, when he and Carel were establishing their own label and realised a whole new generation of customers were interested in gloves as fashion statements, not because of social convention or practicality.

To revive the fortunes of Causse they turned for help to the top Parisian hotelier Jean-Louis Costes, also from the Aveyron, and were amply rewarded. Costes not only stumped up 25 percent of the capital needed but also persuaded his friend Gerard Boissin with whom he relaunched the distinctive Laguiole knives, to do the same, so the company's future is assured.

It was nearly too late. By 2003, there were only a handful of people who still had the skills to make fine gloves. It takes between three and five years for people to acquire the necessary expertise and there were no longer any apprenticeships or schools in France which taught glove-making.

A model walks on the runway at the Christian Audigier Spring 2008 fashion show

From the outset Causse had to have a policy of training -- and now has trained about 20 of its 40 staff.

"Gloves are actually very complex to make. A simple classic glove takes a minimum of two hours, more like four and on average our gloves take eight hours. There is no upper limit for a couture glove, it can take days," Rubio says.

From stretching the pelt to give the glove its essential elasticity and cutting, which is always done by men, to the fine stitching, never more than a millimetre in diameter, which is undertaken by women, there can be as many as 100 different operations involved. One step wrong and a glove is discarded.

From its new premises designed by a top architect, Causse produces 25,000 pairs of gloves a year, but with virtually the same tools as 100 years ago. The only difference is that sewing machines are now electric.

A model presents a creation by British designer John Galliano for Christian Dior

Nearly 80 percent of production is for high fashion's luxury houses, notably Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Hermes. But Rubio is hoping the balance will change, as Causse has just opened a shop for its own label gloves in the prestigious Rue Castigilione, in the heart of Paris' fashion district, a stone's throw from Chanel's headquarters and the Ritz and Intercontinental hotels which host many of the couture catwalk shows,

And Rubio acknowledges the benefits of working with the top luxury brands, because the research they do on their behalf is honing their own workforce's skills.

Chanel's designer Karl Lagerfeld is a big fan, who recently put in an order for no fewer than 200 pairs, all made to his special specifications with just the last digit removed.

"People in Millau live and breathe gloves. They are so glad that somebody is trying to restore it to its former glory," Rubio says.