This fall, fashion houses rolled out collections featuring materials and techniques that not only demonstrated the technical prowess of the mills, but also the creativity of the designers.

At Calvin Klein, Francisco Costa developed a bonded velvet with a rubberized finish, but softened the techy material by slashing it with laser cuts. "I wanted to see the surface evolve," he explains.

And that evolution, moving from sheer innovation toward more expressive garments, was key for many New York designers.

At Christian Cota, a blouse covered in individually printed and embroidered sequins looked practically Pointillist. For Y-3, Yohji Yamamoto called upon Brooklyn street artist Momo to add edge to a few separates with his graffiti-like work. "It's the streety parts of New York that inspire me," says Yamamoto. "Momo's art was a perfect companion to my vision."

In Milan, things were beautifully low-tech. Miuccia Prada's lush velvet brocades for Prada were produced on late-19th-century looms with a capacity of only 25 meters of fabric a day. Meanwhile, at Dolce & Gabbana, the designers' Surrealist bent was emphasized by woven matelasse (quilted fabric), puckering and hand applications of lace and moonstone-like disks.

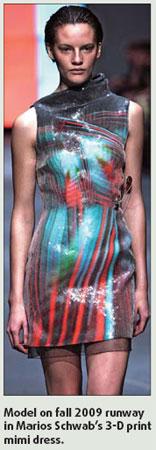

London's Marios Schwab, in contrast, used cyan and red anaglyphic 3-D prints on some of his dresses. Though they were coated with a layer of transparent sequins, the patterns took on dimension when show attendees saw them through 3-D glasses.

Paris designers took a more measured approach. Nicolas Ghesquiere softened his futurist vernacular for Balenciaga, using superluxe silk and detailed pearl embroidery. And John Galliano used fabrics to construct dreamy folkloric silhouettes.

Dries Van Noten took his inspiration from nature. He photocopied flowers, reptiles and leopards, then folded the images and copied them again before applying the Xerox-chic prints onto silk fabrics. By turning a piece of modern-day office life into textile art, he proved there's no time like the present to be creative.