May 4, 2009: Kenya’s textile manufacturing industry -- until recently one of the fastest growing segments of the economy -- is caving in to competitive pressure in key export markets, taking with it thousands of jobs that analysts say will take years to recover.

May 4, 2009: Kenya’s textile manufacturing industry -- until recently one of the fastest growing segments of the economy -- is caving in to competitive pressure in key export markets, taking with it thousands of jobs that analysts say will take years to recover.Data from the Kenya Apparel Manufacturers and Exporters Association (KAMEA) indicates that the industry, which four years ago had 36 players and employed more than 32,000 people, has shed nearly three quarters of those jobs after 21 players closed shop.

Industry insiders say a third of the remaining 15 players are under intense pressure and may close shop before the end of the year sweeping away a proportionate number of the remaining 12,000 jobs.

Such unravelling is expected to dampen hopes in the cotton sub-sector, which has only recently showed signs of recovery after nearly three decades in the doldrums.

Jaswinder Bedi, the KAMEA chairman, reckons that the industry is particularly vulnerable to increasing pressure for higher wages, competition from second hand garment imports and high cost of inputs.

The latest industry data is being published at a time when Nairobi is preparing to host the eighth Economic Forum of the Africa Growth and Opportunities Act (Agoa) in August.

Agoa is a US government legislation that was enacted in 2000 to provide a window for duty free and quota free market access to African manufacturers of textile and 6,000 other products.

The forum is an annual platform where countries that are eligible to export goods to the US under Agoa review the impact of the scheme and discuss new ways for participating countries to increase their trade volumes under the Act.

Under the Agoa, Kenyan apparel exports to the US increased from six million pieces worth $30 million in 2000 to 63.3 million pieces worth $240 in 2007.

Agoa was initially intended to end in 2008 but African exporters got a lifeline when it was extended to 2015.

A recent phase out of quarters in the international fabric and apparel trade under the World Trade Organisation has however made it more difficult for Kenyan exporters to penetrate the US market where they have to compete against seasoned low cost producers such as China.

Trade minister Amos Kimunya

Official statistics show that the sale of apparel in the US declined from $263 million in 2005 to $150 million in 2008 casting gloom over the future of the industry.

Trade minister Amos Kimunya

Official statistics show that the sale of apparel in the US declined from $263 million in 2005 to $150 million in 2008 casting gloom over the future of the industry. Mr Bedi attributes the dip in sales to a steady fall in global prices that have lowered the total worth of the industry.

In 2005, for instance, apparel exports were sold at a price of $4.39 per unit but this declined to $3.47 in 2008.

Trade minister Amos Kimunya says Kenya must increase the competitiveness of her apparel industry if it is to continue commanding sales in the US market.

“Although there is immediate need to make the Agoa more predictable, in the long-term, sustainability of our position the US and other export markets depends on increased competitiveness of our production,” Mr Kimunya says in a statement on the forthcoming Agoa forum.

But even as the government urges local manufacturers to increase competitiveness, new statistics indicate that Lesotho and Madagascar have overtaken Kenya as leading exporters of apparel to US under Agoa.

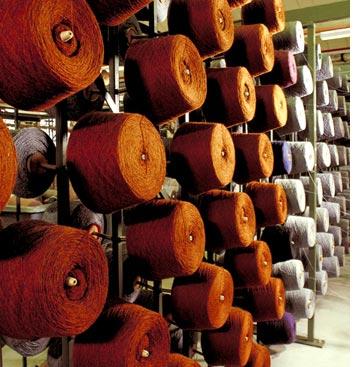

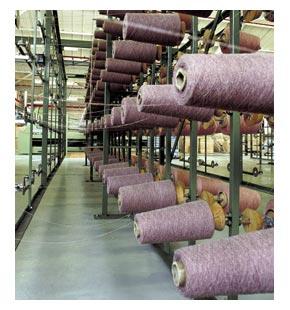

Economic survey 2008 indicates that the textile sub sector grew by 1.8 per cent in 2007 while the manufacture of cotton woven fabrics rose by 10 per cent from 8.4 million square metres to 9.3 million square metres.

Industry players say focus is now shifting to increasing domestic cotton production with the aim of easing the raw materials shortage and creating jobs in the sector.

Deliberate government action has seen Salawa Cotton Ginnery in Baringo reopen boosting cotton farming in the North Rift after years of a lull.

Cotton Development Authority managing director, Albert Chepyegon, says the government is offering farmers free seeds and pesticides in support of the industry. Besides, he said, plans are under way to pay farmers instantly upon delivery of cotton to the ginneries.

Local manufacturers say nothing short of government subsidies will enable the sub-sector to develop enough muscle to compete with large textile manufacturers from India and China.

“The industry sentiment is that the government of Kenya is not passionate about the sector and thereby does not motivate the players” said Mr. Bedi at a forum of textile companies operating under the Export Processing Zones.

The industry has yet to fully recover from lost orders resulting from the post-election violence setback they suffered in 2008.

The violence, which paralysed the transport system for nearly two months, left exporters with heaps of garment they could not ship out of the country.

Among the inputs that players want subsidized is electricity which accounts for 35 per cent of the total input of spinning firms and 20 per cent of all input of fabric manufacturers.

Among the inputs that players want subsidized is electricity which accounts for 35 per cent of the total input of spinning firms and 20 per cent of all input of fabric manufacturers. Kenyan firms pay approximately $0.17 per KWH while its competitors in China pay $0.4 KWH.

“How do we compete in the international markets when we are paying more than double on our key input for manufacturing the apparel. The government should consider waiving all electricity levies to textile firms” said Mr. Bedi.

The manufacturers want the government to adopt export credit guarantee schemes to shield exporters by offering pre-export finances.

Some are lobbying for forced funding programmes for the textile sector with shared risks between commercial banks and the government so as to avail the much needed cash injection into the textile firms facing closure.