The economy may be floundering, but at last week's graduate shows, creativity flourished. Harriet Walker rounds up the highlights of the student season

The economy may be floundering, but at last week's graduate shows, creativity flourished. Harriet Walker rounds up the highlights of the student season

When Alexander McQueen showed his graduate collection in 1994, fashion editor and impresario Isabella Blow bought it in its entirety and set him on the road to international recognition as one of the most talented fashion visionaries of the twentieth – and twenty first – century.

"The last recession brought a burst of creativity," says Willie Walters, course director of the BA fashion degree at London's Central St. Martin's. "Young designers understood there were no jobs out there, but they soldiered on with a hope and a prayer. It takes hard times for creativity to really be appreciated."

These are hard times indeed in which to be a young designer, but the graduate shows in London last week saw passionate displays of ingenuity and resilience, as well as hard work and natural talent. After the boom years of the late Nineties that saw British graduates taking some of the top jobs in the industry – with Galliano at Dior, McQueen at Givenchy, and Phoebe Philo followed by Stella McCartney at Chloé – it seems fashion's wheel of fortune has gone full circle, and while the job market may be inert, the reaction amongst young British designers is anything but.

Graduates seemed freed up by the commercial shrinkage and were able to express themselves more conceptually. It showed in their many different takes on deconstruction: Yun Jeong Yang at London College of Fashion showed reconfigured skirt suits that morphed into overcoats, and at the Royal College of Art, Jae Wan Park's traditional menswear collection featured extra sleeves worked into suits as lapels, and jackets with waistcoats attached at the back. It's a method of questioning the role of the designer in a culture used to excess and now cutting back, a way of ushering in the 'new' by developing a different mode of dressing and creating other forms of garment, just like Yohji Yamamoto did in the Eighties, the last time we had more than we needed or could afford.

Anatomical imagery was another trope used to the same effect, both unnervingly and with a sense of humour. Central St. Martin's graduate Kye showed a sweet knitted jumper decorated with a to-scale representation of the model's digestive system. Sarah Benning, from the University of Westminster, had leggings really earning their soubriquet, painting them and rubber shift dresses with detailed Vesalian renderings of muscles and tendons, while the RCA's Matthew Miller made bibs for his tuxedo shirts out of skeletal bone cut-outs, the arms of which swung free next to the model's. CSM knitwear student Caroline Jarvis showed a baby pink sweater embellished with a plastic spine, perhaps to remind us that in even the most romantically-minded of men there need also be a bit of backbone.

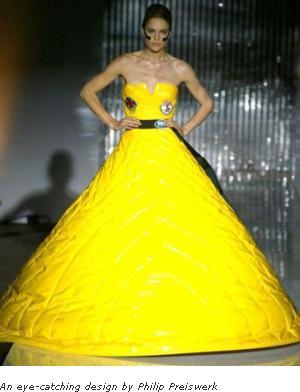

Opulence was a variant refutal of the economic gloom though. In a show of extreme media savvy, fashion and marketing student Philip Preiswerk at CSM presented a collection inspired by Kill Bill and made up of six enormous, crinoline dresses in various eye-popping shapes and colours. These were show pieces indeed: singer and directional clothes horse Lady GaGa has reportedly been in touch with Preiswerk about purchasing or commissioning his designs. It may be an extreme case in point, but it's proof that there's still a lot of value attached to British fashion graduates, who are pored over by this restless global industry.

"There's so much tribalism in the UK," says Richard Bradbury, CEO of Graduate Fashion Week sponsor River Island, "and it's that diversity coming out of our universities that makes the UK very appealing , whether to Gucci or Prada, or Nike or Puma." Now in their fifth year of sponsorship, River Island boasts an impressive selection of GFW alumni in their creative team and has recently launched a range of pieces by graduates for their stores; like ethically sourced meat, you can track who has worked on each piece and how they started out. "We typically take in a lot of graduates every year," adds Bradbury. "We're a fashion business and we need fresh talent coming in." There was talent in abundance in London last week, cementing its reputation as creative capital, where new names and raw talent are not only nurtured but held up as exemplars. "If fashion is personal expression through clothing, then Britain is its head and heart, and the graduates are its lifeblood," says milliner Stephen Jones poetically.

There was a sense at the shows of a laying bare of the very design process itself. Many graduates used layering to show off the technical intricacies of their pieces. At the RCA, Anna Ruberg used large interlinked swatches of suede to create dresses held together, it seemed, by the very holes in the pattern. And winner of the LCF fashion textiles award Alicija Aputyte showed jackets and tops with 'tunnels' in them, through which belts and cords were visibly threaded, to create a confluence with the inside and out of the pieces and therefore with the ideas involved in their genesis.

And when the talent weren't showing off their skills, they were modestly hiding them in subtle and elegant pieces. A crop of designers looked to the minimalism of the early Nineties – a recession trend if ever there was one – and showed pared down silhouettes made from neoprene (in the case of Neil Young at CSM) and austere boiled wool, as at LCF's Hannah Beth Stenberg. Siofra Murphy at the RCA gave us new, or luxe, minimalism in discreet futuristic shapes made from elaborately textured and printed fabrics, mixing "over-decoration in a tasteful way" with "starkness and a measured linear approach." If this is a sophisticated shell into which we can retreat in hard times, then some designers also offered heavy-duty armour to fend off the financial apocalypse – Asger Juel Larsen had male models clad in chain mail vests and hoods at LCF, and Kim Choong-Wilkins at the RCA protected effete models in voluminous and ironically bourgeois Oxford bags with chain mail knits.

It should be clear then, that fashion's class of 2009 are ready to face whatever the industry and the economy may throw at them. "In times like this, our students get more and more creative," asserts Lucinda Chambers, fashion director of British Vogue. "After all, in this country, we're used to doing things on no money."