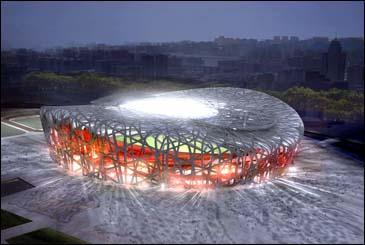

Nicknamed `bird's nest' due to its giant lattice-work of angled metal girders, the Olympic stadium is taking shape in Beijing. The government has scaled back the budget, promising a stadium on a more modest scale.

Hurtling forward,the nation reimagines itself by importing design from around the world.

They've been called invaders, impractical eggheads and barbarians intent on destroying the feng shui, the ancient art of harmony and balance. They are tripping over themselves to work in Beijing. And, like it or not, they're remaking the face of China.

As the Middle Kingdom bounds onto the world stage, it's turning wholesale to foreign architects to trumpet its arrival. The ``foreign devils,'' as outsiders were once called, not only lend prestige and glamor to a project, they also bring design expertise and a knowledge of materials that many of their Chinese counterparts still lack.

With explosive economic growth in its pocket and the 2008 Beijing Olympics on the horizon, the world's most populous country is on a building spree dwarfing those that remade New York and Chicago in the early decades of the 20th century.

All the bobbing and weaving of construction cranes has such global architectural stars as IM Pei, Rem Koolhaas and Norman Foster, along with many of their not-so-famous brethren, clamoring for a piece of the action. The big attraction is an eager client with money to burn and a willingness to entertain all sorts of out-there designs.

``People see China as the Wild West,'' says Zhang Xin, a developer and design expert whose pioneering SOHO apartment complexes are reshaping Beijing. ``It's the land of cowboys.''

A look across the Beijing or Shanghai skyline also calls to mind a sci-fi landscape, one crowded with pagoda-hat skyscrapers, roofs that suggest stealth bombers, and buildings topped by gaudy pink balls and what look like cruise missiles. Moviemakers searching for a 22nd century set find themselves gravitating toward Shanghai, Asia's flashiest city, which now boasts 6,000 buildings more than 10 stories high, along with the world's only commercial maglev [for ``magnetic levitation''] train and the world's tallest hotel.

This rapid transformation of China's cityscapes is not without controversy, however. Take Beijing's National Grand Theater - or, as it's been variously dubbed, ``the eggshell,'' ``the blob'' and ``the tomb.'' The oblong dome, sitting astride Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City, is scheduled to be finished next year on some of Beijing's choicest real estate.

For many traditionalists, the arts complex, designed by French architect Paul Andreu, epitomizes all that's wrong with the foreign invasion of design talent. After four years of work and US$365 million (HK$2.85 billion), the titanium and glass behemoth, critics say, looks like a traditional Chinese tomb - hardly the right feng shui for the spiritual heart of China.

Chinese architects have petitioned Beijing to scrap the project. Environmentalists have slammed its high anticipated maintenance costs. And engineers have argued that it's unsafe, a charge fueled when an Andreu-designed airport terminal in Paris collapsed in May, killing four people. Although investigators have blamed the accident on the terminal's construction rather than its design, the hullabaloo sparked another nickname for the Beijing project: ``the broken egg.''

Andreu takes it all in stride. ``I have nothing against the eggshell nickname,'' he says. ``An egg has a thin shell that is very strong. And it's a very simple form with enormous promise of life and complexity. With three halls and lots of circulation, I hope this project is a promise of life.''

The national theater is far from the only space-age structure raising eyebrows here. There's also the showcase Beijing Olympic Stadium by the Swiss team of Jacques Herzon and Pierre de Meuron, famous for Tokyo's Prada store and London's Tate Modern museum. Like the arts complex, the 100,000-seat ``bird's nest'' stadium, made of interlocking bands of gray steel covered with a transparent membrane and a retractable roof, has been hit for its price tag and unusual design. The government recently scaled back the budget by almost half, to US$274 million, and slowed construction, promising to finish the stadium on a more modest scale.

But perhaps the most eye-catching project fueling this debate over the limits of modernity is the Chinese Central Television headquarters in Beijing's central business district. It resembles two L-shaped towers leaning against each other to create a continuous loop.

The design by the Dutch firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), led by Koolhaas, has endured years of public debate and seen its projected cost double to US$600 million, a huge figure in a nation where farmers earn less than US$300 a year.

It's so technically complex that scores of engineers reportedly required more than a year to work out the stresses on the supporting I-beams. Yet despite heaps of criticism, several delayed groundbreakings and rumors that Premier Wen Jiabao wanted to kill the project given the high price tag, the 55-story structure finally got the go-ahead in September. Ole Scheeren, an OMA partner, sees the design as a hybrid of futuristic elements and geometric forms found in ancient Chinese tradition. But the shape is less important in its own right, he says, than how it will influence the way people use the building.

Scheeren argues that OMA's biggest contribution lies in creating communal spaces and a natural flow that will draw disparate parts of the network together, redefining the work environment. ``This is very important when judging it,'' he says. ``That's how the shape was born.''

Even as critics slam these and other high-profile projects, defenders counter that the loudest complaints are coming from those who enjoyed a domestic monopoly before the foreign invasion and who resent the competition. Furthermore, these advocates contend, China was in need of a shake-up after decades of isolation. Much of what conservatives view as traditional architecture is foreign anyway, they add, and includes many Soviet-inspired socialist designs adapted originally from French beaux-arts models to glorify Marxism, itself a German ideology.

``This kind of debate on how to integrate the new and the old is good for China,'' Wang Weiqiang, an architecture professor at Tongji University in Shanghai, says. ``We'll never return to wearing traditional Chinese robes. But even if we wear Western suits, we're still Chinese.''

Good building projects often incite controversy in any country, others say, pointing to the glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre by American architect Pei; it initially came under blistering attack from the French, only to emerge as an indispensable and well-loved Paris landmark.

Still, although China may be producing some of the newest architecture around, its system doesn't always ensure the best structural results. The country's transition from communism has left a legacy of corruption, questionable land ownership, an opaque legal system, shoddy construction methods and limited experience commissioning large projects.

In the public sector, decisions are often made by Communist Party officials who see impressive buildings as key to a promotion. Then they assign a few bureaucrats with limited knowledge of contracting, cost control, project management, aesthetics or problem solving to carry out those decisions.

Some of this happens with government projects anywhere, but critics say the problems in China are compounded by the lack of democracy or taxpayer scrutiny under its top-down governing system.

Nearly every foreign architect in China for any stretch of time can recount his or her share of nightmares. Jon Jerde, the American architect famous for his innovative approach to shopping centers, including Minnesota's Mall of America and the Universal CityWalk, has completed several successful projects in China over the last decade. Mention the Super Brand Mall in Shanghai's Pudong district, though, just across the Huangpu River from the historic Bund, and Jerde lets out an immediate groan.

Originally envisioned as a shopping center ensconced in a lush park built around a heavily trafficked ferry terminal, the project ran into trouble almost immediately. The developer encountered financial problems and dropped out, regulators kept raising the bar, the owners scaled back the design to just another big-box shopping center, and Jerde was given the boot.

A few years later, when the developers realized they were going to lose their shirts, they rehired Jerde. He tried his best to patch the project together at the eleventh hour. But in a death knell, city planners relocated the ferry terminal so passengers flowed into another developer's mall, ruining the entire premise.

``It was a wake-up call how awful things can get in China,'' Jerde says. ``It was a horrible experience.''

The pressure to do things quickly and cheaply means far less follow-up work. Jerde Associates tends to bill as many as 40,000 hours on a major project, but in China, that figure is generally closer to 8,000. And many of those hours are spent persuading a client not to dispense with all the trees, wandering paths, waterways and other features that make a project distinctive, as developers rush to fill every square inch with shops.

``We fight these same issues on every project,'' David Moreno, Jerde's design principal, says. ``We have to battle the forces pushing for dumbbell shopping malls.'' Some foreign architects respond by selling cookie-cutter designs they've created elsewhere, with little deference to local considerations.

``You see these Northern European-style steep roofs, meant to keep the snow off, being built in southern China,'' says Xing Tonghe, chief architect with the Shanghai architectural firm Xian Dai, which helped design the critically acclaimed Jin Mao building in Shanghai, China's tallest, with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

``It's ridiculous.''

China's building spree has also spurred an ongoing debate over preservation. Although the country arguably invented city planning thousands of years ago, as evidenced by the well-ordered grids of its ancient capital cities, its headlong impatience to become world class overnight often results in messy patchworks, as traditional courtyard homes are razed, the faster the better, to make way for skyscrapers as flashy as possible.

``It's not the first time the whole nation has suffered from a bout of overconfidence,'' Zhou Rong, assistant dean of the architecture school at Beijing's Qinghua University, says. ``In the 1950s, you had the Great Leap Forward, as China argued it could catch up with Britain in five years, the US in 10. Now they're trying to do that all over again.''