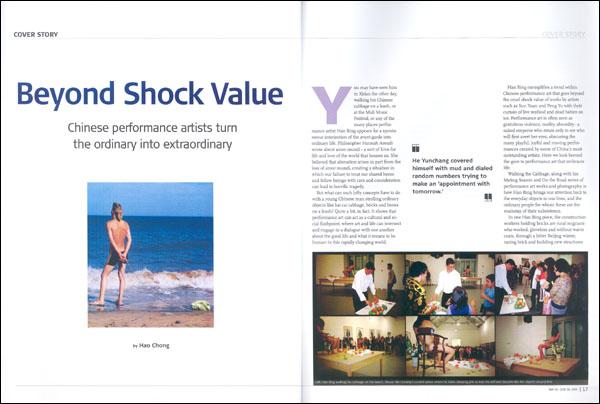

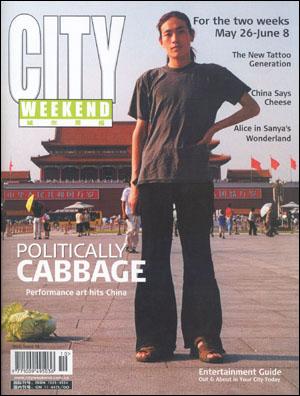

You may have seen him in Xidan the other day, walking his Chinese cabbage on a leash, or at the Midi Music Festival, or any of the many places performance artist Han Bing appears for a spontaneous interjection of the avant-garde into ordinary life. Philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote about amor mundi - a sort of Eros for life and love of the world that houses us. She believed that alienation arises in part from the loss of amor mundi, creating a situation in which our failure to treat our shared home and fellow beings with care and consideration can lead to horrific tragedy.

But what can such lofty concepts have to do with a young Chinese man strolling ordinary objects like bai cai cabbage, bricks and bones on a leash? Quite a bit, in fact, and as such, it shows that performance art can act as a cultural and social flashpoint, where art and life can intersect and engage in a dialogue with one another about the good life and what it means to be human in this rapidly changing world.

Han Bing exemplifies a trend within Chinese performance art that goes beyond the cruel shock value of works by artists such as Sun Yuan and Peng Yu with their curtain of live seafood and dead babies on ice. Performance art is often seen as gratuitous violence, nudity, absurdity - a naked emperor who struts only to see who will first avert her eyes, obscuring the many playful, joyful and moving performances created by some of China's most outstanding artists. Here we look beyond the gore to a performance art that embraces life.

Walking the Cabbage, along with his Mating Season and On the Road series of performance art works and photography, is how Han Bing brings our attention back to the everyday objects in our lives, and the ordinary people for whom these are the mainstay of their subsistence. Bricks were introduced as the architectural answer to modernity in 1980s China. Quickly, however, like so many ordinary peoples' hopes that were raised and then shattered by the onslaught of capitalism with Chinese characteristic, mass lay-offs, rural displacement, dislocation and the growing gulf between rich and poor, bricks became yet another symbol of backwardness, yet another form of refuse for migrants to collect from razed buildings.

In one Han Bing piece, the construction workers holding bricks are rural migrants who worked, gloveless and without warm coats, through a bitter Beijing winter, razing brick and building new structures of steel, concrete and glass, and in the end did not even get paid. In Mating Season No. 9, at 798 Art Factory's 2005 Dashanzi International Art Festival, Han Bing lay curled around a chunk of rubble, surrounded by clumps of cotton, naked save an opaque stocking. He left a note asking the crowd where warmth could be found in this prosperous yet indifferent time.

Other Mating Season performances involved Han Bing hugging the shoes of foreigners at a foreign language institute, reminding us that the ground beneath our feet is common ground. Last weekend he brought a flock of strangers together in Tongxian outside the Tanling Gallery to stand together hugging their shoes and remembering their common roots.

Other Mating Season performances involved Han Bing hugging the shoes of foreigners at a foreign language institute, reminding us that the ground beneath our feet is common ground. Last weekend he brought a flock of strangers together in Tongxian outside the Tanling Gallery to stand together hugging their shoes and remembering their common roots.Most moving, however, is a picture of his extended family in their home village in Jiangsu, standing together and clutching cabbages, the most basic staple food, tight to their chests. This powerful image speaks of home, comfort, solidarity, survival and strength through love.

Ma Liuming, a world-renowned artist from Hubei, was one of China's first performance artists to gain international attention and perform across the globe. As a member of the edgy Beijing East Village artist colony, he participated in the celebrated Making the Unnamed Mountain a Meter Higher (1994), and went on to cultivate Fen-Ma Liuming, a persona that embodied gender ambiguity, creating space for self-making in the cracks between traditional gender categories.

In a series of nude performances, with his face made-up like a woman, Fen-Ma Liuming became the incarnation of possibility for transcendence of the categories that define, constrain and divide us. Inviting the audience to participate in the performances, he suggests that we can each take part in the making of the order of things.

One of his most powerful performances was a walk along the Great Wall (1998 and 2004), in which Fen-Ma Liuming traversed this historically symbolic line between civilization and barbarianism, almost hovering above it, showing it to be nothing but a human edifice, on which the shoots of weeds, grass and tiny flowers had tenaciously grown, forcing themselves through the cracks in what once seemed monolithic.

His current series (since 2001) involves dialogues with works of artists ranging from Cezanne to Beuys, and features a mediation on the artist himself as an object of art. By taking sleeping pills, the artist's self and conscious volition gradually disappear, until he is no different from the apples on the table or the carved chair on which he sits.

Yunnanese He Yunchang is another artist whose work contains elements of will power, humor and joy. Ah Chang is famed for his absurd yet touching attempts at the impossible, such as moving a mountain by attaching ropes to the ground and pulling with all his might for half an hour (1996), covering himself with mud and dialing random numbers trying to make an "appointment with tomorrow,"(1998) or trying to out-drink or out-wrestle a hundred people in a row. In Dialogue with Water (1999), He hung upside down from a crane over the Lianghe River in Yunnan, and used a knife to cut the river in half for 30 minutes.

Another kind of dialogue with nature is currently taking place at edgy real estate baron Pan Shiyi's Jianwai Soho in Beijing. On May 1st, Shandong poet Ye Fu ascended a manmade bird's nest in the plaza there to live in the unnatural "nature" of the capital for a month. Organized by Shanghainese art critic and curator Zhu Qi, this month long performance is exceptional in that millions of people are observing Ye Fu's daily experiences via the worldwide web on www.sohu.com.

Ordinary people are participating in the performance, ranging from a day laborer, to Shen Tong, a well-known lawyer, interpreter and art connoisseur, who spent her birthday living for a day in the "nest," and debated our reliance on material social comforts. How will this experience change Ye Fu, before he comes back down into society at the end of the May? Each of us can to take part, and fulfill the most important aspect of the spectacle - stimulating public discussion about the role of art in our everyday lives and society.