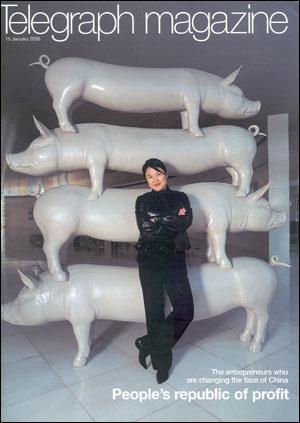

Visitors to Zhang Xin's sweeping mezzanine offices in downtown Beijing are greeted on arrival by a pair of life-size white pigs. There is another pair of pigs standing sentry down the corridor, and a sculpture of four pigs stacked on top on each other like porcine Chinese acrobats by a giant window. In China pigs symbolize good fortune, so I ask Zhang if this is the significance. "Not really," she replies. "They are one of the artworks we commissioned. I think the artist just likes pigs."

This idiosyncratic touch is typical of SOHO China, the property development company that 39-year-old Zhang founded with her husband, Pan Shiyi. The company has made a name for itself by breaking with the drab proletarian past and infusing China's modern architecture scene with an audacious, offbeat energy. Zhang has been dubbed a "young urban visionary" and a "dynamic trendsetter". In October, Fortune magazine also claimed she was "possibly the wealthiest woman in China."

"That's just silly," laughs Zhang, sitting at her large, pale wooden desk with a cup of caf latte. "I have no idea who the wealthiest woman in China is, but I don't think it's me." If it isn't Zhang, it would be a devilishly close contest. As the creative force behind the Beijing-based company, she commissions vast building projects designed for China's sophisticated new elite. Her latest, Jianwai SOHO, is a futuristic complex of office, residential and shopping towers, all glittering glass and blinding white metal, in the most sought-after spot in the capital. Sales generated for the company by the complex so far total seven billion yuan ( 435 million.

The distinguishing feature of all China's successful entrepreneurs is that, unless they were the sons and daughters of corrupt Communist officials (as many of those who profited in the first wave of economic openness were), they worked their way up from nothing. Zhang, stylish and direct, struggled even more than most. Her Chinese-Burmese parents divorced when she was small and, aged 14, she moved to Hong Kong with her mother. The two shared a one-room flat, working in garment and electronics sweatshops by day to pay the rent. By night Zhang studied at evening classes to complete her school education. Today she is amused by the constant media focus on her sweatshop background, but she admits it was tough at the time. "I'm not exactly a factory girl made good. My parents were intellectuals whose careers, like many people's, were disrupted by the Cultural Revolution. We fell into a classic poverty trap but I always knew I'd find my way out."

As a Hong Kong resident Zhang was eligible to apply for a grant to enter a British university. She won a place at Sussex to study economics, and then went on to do a graduate degree at Cambridge. In her late 20s she worked as a merchant banker on Wall Street and in Hong Kong. The catalyst for her return home was her husband Pan, a Beijing-based businessman whom she fell in love with during a work trip to China in 1994 and married five months later. Still, Zhang says she was more than ready to test her skills in the freewheeling chaos of new China. "I felt this was an amazing moment in our history, that there was a real chance to participate in the grand process of modernizing the country and I wanted to be there," she says.

As a Hong Kong resident Zhang was eligible to apply for a grant to enter a British university. She won a place at Sussex to study economics, and then went on to do a graduate degree at Cambridge. In her late 20s she worked as a merchant banker on Wall Street and in Hong Kong. The catalyst for her return home was her husband Pan, a Beijing-based businessman whom she fell in love with during a work trip to China in 1994 and married five months later. Still, Zhang says she was more than ready to test her skills in the freewheeling chaos of new China. "I felt this was an amazing moment in our history, that there was a real chance to participate in the grand process of modernizing the country and I wanted to be there," she says.Zhang and Pan, 42, a former executive at a state oil company who was a fledgling real estate entrepreneur when Zhang met him, started SOHO China together in 1995 just as the idea of private home ownership caught fire. The government had liberalized the property market a few years earlier, first by encouraging salaried workers to buy their state-owned flats, and then by offering mortgages to buy privately-built homes. "We had a whole nation of first-time buyers on our hands," says Zhang. "Also a nation who hated tradition and wanted to erase the recent past. It was so raw and open." Although Zhang's vision was starkly ultra-modern at the outset - she wastes little energy lamenting the loss of Beijing's traditional alleyways and imperial courtyards ("there just isn't space") - she avoided the temptation to throw up jerry-built highrises like so many other private developers. "We wanted to use innovative design and daring technology to reflect people's aspirations," she says.

One of Zhang's early projects was Commune by the Great Wall, a collection of extravagantly avant garde villas designed by 12 Asian architects at a total cost of US$24 million. Nestled in the hills around China's famous ancient landmark, the modern villas seem to issue a direct challenge to history. Zhang intended to sell them to private buyers as weekend getaways. However, after the villas won a prize at the 2002 Venice Biennale she decided to keep them as contemporary showcases to "inspire new models of Chinese architecture."

Her main projects now revolve around the notion that, in the age of portable, wireless technology, busy Chinese urbanites need to combine their living and working environments in one stylish space. The company's name, SOHO, stands for "Small Office, Home Office" and the concept is a huge hit. Not least for Zhang herself, who lives in an apartment in the newest SOHO complex, Jianwai, with Pan and their two sons, aged four and six. Although she could afford to live in a mansion, Zhang says the centrally-located building suits their needs well. "Beijing is a global city with all the usual trappings, and we lead a very metropolitan lifestyle. We try to put our sons to bed ourselves and then we go out for dinner, entertain clients and visitors, and attend work functions most nights of the week. Of course having money makes a massive difference to our sense of wellbeing, but day to day we lead a fairly ordinary life."

In fact, as global attention is increasingly focused on China as the next great superpower, Zhang says her home city has become an international social hub. "I rarely have to go overseas to visit old friends, because they're all coming here on business." This state of affairs is light years removed from the Beijing of a decade ago, when the capital was only just recovering from the damage done to its international standing by the Tiananmen Square killings. Although democracy is still no closer, Zhang says Chinese communism barely impinges on her life or business at all. "The bottom line is that the government doesn't really care how much money people like me make or what we do with it as long as the economy is healthy."

Zhang is an archetypal modern jetsetter, flying to Europe and the US every month on business. She takes her sons and their nanny with her during the boys' holidays from school in Beijing. Pan usually stays at home to deal with business inside China. "The division of labour works out that way partly because I speak English. But also because China is still chauvinistic and local businessmen find it more comfortable to deal with my husband than with me," she explains. "Besides, I don't want to sit around with men smoking, drinking and telling dirty jokes." Not everything changes, then. Zhang gives the impression that almost nothing fazes her, but whenever she needs to let off steam she goes hiking in the hills around Beijing with her family. She flips through some photos from as recent weekend to show me pictures of her two sons swaddled in thick outdoor jackets, their faces flushed with the icy mountain air.

As for the future in China's urban jungle, she and Pan plan to continue their pioneering role in the property industry, introducing cutting-edge architecture wherever they can. "It's what people expect of us," Zhang says. "And it is what we expect of ourselves."