[By Zhou Tao / Shanghai Daily]

In March I gave a speech at the 2011 China Development Forum on what I call the "social bubbles" in China's property market.

Contrary to popular notions, housing is more a social product than a pure economic one. Everyone has his or her right of abode. From this perspective, I think early reforms of the country's property sector are grossly erroneous.

Policy makers then were ignorant of the social implications of treating housing as merely a commodity. Over the years, many government officials and high-level think tanks have endorsed the bid to build real estate into China's "pillar industry."

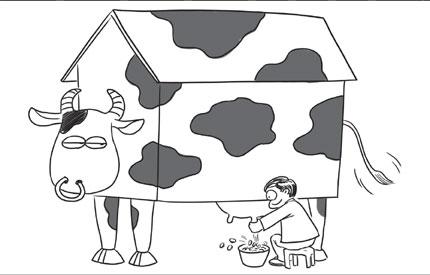

This, in my opinion, is a colossal mistake. Real estate was behind the past booms of the US and European economies, but none sanctified it as a "pillar industry." Some local Chinese governments, however, hold up real estate as their cash cow, despite the risks of real estate boosterism. We cannot ignore the extent of bubbles that lurk beneath the facade of exuberance.

Given media coverage and my own observation, I dare to presume that the property market is rife with speculation. In some Chinese cities, whole residential buildings are unlit at night, an indication of vacancy. Yet there still are scholars who cozy up to interest groups and justify sky-high home prices on the grounds that the country has a large population of wannabe home owners representing "rigid demand."

Dubious premises

But that reasoning fails to convince, for it is predicated on dubious assumptions: First, China's growth is linear, or its property boom won't last; second, for every house built there is a buyer; third, the supply of land on which houses are built is abundant. These flimsy premises aren't taken into account when "hack scholars" spin their bubble-free theory.

If we examine the sources of local governments' revenues, we'll find 60 to 70 percent are generated by the property sector.

This shocking level of dependency on real estate is definitely unsustainable. I've been to many parts of Guangdong Province, where much of the idle land there has been sold or marked for redevelopment.

This short-termism owes a lot to China's political system, under which officials are rotated every two terms. They don't care if reckless land sales will deprive successors of their lifeblood. Nonetheless, the cash-strapped successors can now turn to property tax.

I've argued before that taxes on home sales may curb price hikes. I was overly optimistic. For some local authorities, the tax move was no more than a financial response to lower revenues caused by dwindling land supply.

Land sales have almost been the sole lifeblood of political life at the local level. This fact can be attributed to the fiscal reform in 1994, which saw more local tax money gravitate to the central government's coffers. The redistribution of wealth provided the rationale for an unremitting wave of land sales.

The reform did in some cases drain local authorities of the wherewithal to function meaningfully. So it's time to overhaul the outdated fiscal system put in place by the 1994 reform. Otherwise, it'll be futile to dampen the thirst for land sales.

Last year I visited my hometown, a village in Zhejiang Province. I learned that many peasants had their land seized by officials who ruthlessly encroached on farmland, which is forbidden, after land supply in cities ran out. They lied to their superiors about the real size of arable land.

That said, urbanization will be the major dynamic behind China's future growth. But if we compare the Western and Chinese models of urbanization, the difference is plain to see. Western urbanization begins with influx of people into cities, followed by appropriation of land in the countryside.

In China, however, this process is reversed. Here, people's migration and resettlement in cities doesn't matter as much as the seizure of arable land. In a notorious case, some authorities in Chongqing Municipality last year forced college students to give up their rural hukou, or household registration, in exchange for an urban one.

Reversed process

Make no mistake about it. This is not a show of generosity, but a thinly veiled plot to coerce students into abandoning their claim to rural land. Land constitutes the very foundation of human existence. If such official excesses are permitted to fester, China as a society will be stripped of its underpinnings.

The country needs two property markets. The existing one is heavily regulated to lower home prices. I personally am skeptical of the odds of success, because the vested interests - local officialdom, developers, banks and home owners - all stand to gain from high housing prices. Besides, a property market crash would be a disaster for the entire national economy.

So how do we prick the bubbles? One answer is to restrict land supply and reduce land sales.

But a more significant measure would be the government's deeper involvement in the provision of social housing.

In Singapore, 80 percent of its housing is subsidized by the government; the figure in a liberal economy like Hong Kong hovers around 40 percent.

China's mainland's desired rate, at 20 percent, appears way too low. Yet some scholars even think it too ambitious to aim for 20 percent.

The social housing market is meant for the middle- and low-income class who cannot afford a roof of their own at market prices, so its presence has little impact on commercial property.

In 2008, when China and Singapore agreed to build an ecological city in Tianjin in northern China, Singapore proposed that affordable housing account for 40 percent in the planned eco-town. The proposition was met with fierce objection from Tianjin. The two sides finally settled for 20 percent, which became the benchmark proportion when China announced its plans to develop social housing.

China's property market needs to be divided into two segments, one for the haves, the other for the have-nots. Regulators, however, should beware of adopting administrative measures redolent of China's former planned economy, which are bound to fail.

Hong Kong and Singapore's experiences can offer reformers technical guidance. All in all, social housing schemes must be kicked off now, for without them, the commercial housing sector may crumble as well.